Three years before Sept. 11 became synonymous with not only terrorism but airline tragedy and loss of life, another September air disaster left its indelible mark on those involved in the aftermath of the crash.

Swissair Flight 111 — which was traveling between New York City and Geneva, Switzerland — crashed off the coast of Nova Scotia on Sept. 2, 1998, instantly killing all 229 people on board. An investigation deemed the crash to be an accident. An in-flight fire, possibly caused by electrical wiring, compromised the control of the aircraft.

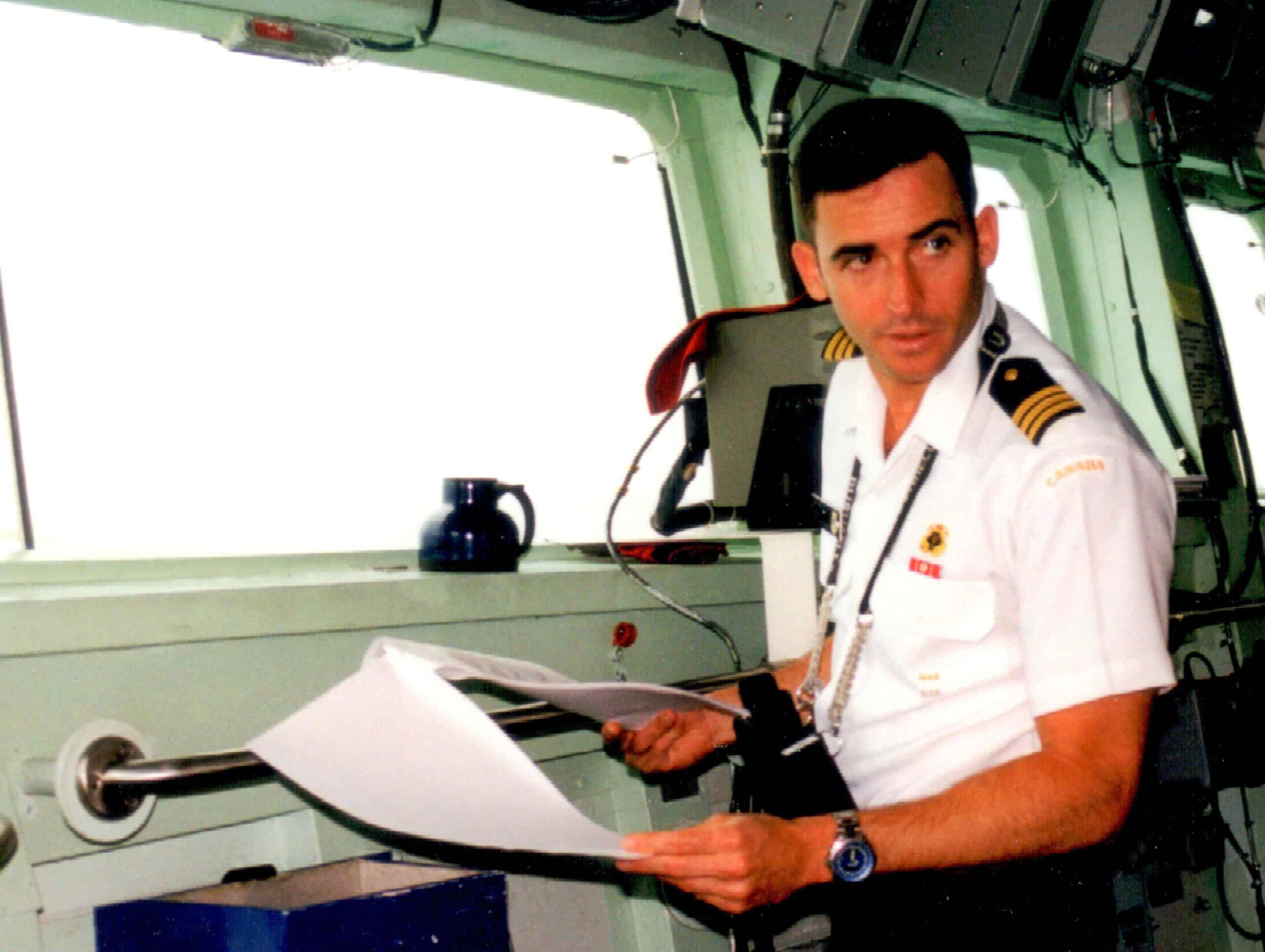

Twenty-five years after the crash, Greg Aikins shared his reflections about his role as the Canadian Navy’s on-scene commander for “Operation Persistence,” the largest marine peacetime operation in Canadian history.

Aikins addressed the effects this experience had on himself and his crew, and how it served as a catalyst for an eventual deeper conversion within his Catholic faith. This was due, in part, to the painful nature of the operation.

“I think my healing has been great and the fact that I have Jesus on my side is huge in all that,” said Aikins.

“When I say that things are better now, boy, if I wasn’t a Christian, I don’t think I’d be able to say the same thing,” he said. “I don’t think the healing that I’ve had would have been possible without Jesus.”

Unexpected mission

Aikins recounted how, at the time of the Swissair crash, he was captain of the HMCS Halifax, a frigate with the Canadian Navy.

His crew was sent to relieve the vessel that had taken on the initial role as on-scene commander during the first few days following the plane crash. “We already knew, by the time that we showed up, that it was a search and recovery operation,” said Aikins.

He explained how the initial responders to the crash hoped to rescue survivors from the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Aikins’ crew was spared the initial devastating realization that there were no survivors. “That was absolutely crushing,” he said.

“We all want to do good,” Aikins continued. “And in this case, we did as good as we could under the circumstances for their family.”

The good which Aikins and his crew sought was to coordinate the recovery of human remains as well as debris from the airplane. The latter would assist investigators in identifying the cause of the crash. They also enforced a large exclusion zone.

Recovery efforts after crash

“We were basically anchored at the debris field,” said Aikins, who estimated that the HMCS Halifax remained at the crash site for a little more than three weeks.

A United States Navy salvage ship, the USS Grapple, was anchored very close to the Halifax. It was involved in daily diving operations. Whenever any human remains were discovered, they would be brought aboard Aikins’ ship because it was the “at-sea morgue.”

Aikins recalled the communal disposition of his crew as one of dignified respect for the task they were undergoing as well as the lives lost. “That was absolutely what we were focused on,” said Aikins. “There was definitely a deliberate tone of caring that was set.”

He noted that this tone wasn’t something officially imparted to the crew, but an inherent understanding. “As sailors, we kind of just got it somehow,” said Aikins.

“We’d actually recovered remains from every single person,” he said. “We felt, as a crew, that that was really important, that we were really doing something important for the families.”

Core values of crew

“Just by coincidence” the number of crew and passengers onboard the Swissair flight, 229 people, was the exact number of the ship’s company when Aikins initially set sail for Operation Persistence. As a cradle Catholic, Aikins’ Christian beliefs informed his approach to these 229 crew members entrusted to him.

“I’ve always believed in servant leadership … and that clearly influenced my leadership style … all through my career,” he said. “I believe that came from my Christian background, without even really knowing that, and not consciously saying, ‘I want to lead like Jesus.’ It was just part of my DNA.”

Aikins recognized how his “cultural Catholicism” resulted in a “certain set of mores and principles that you’re not even aware of, as a Catholic, growing up.”

These values influenced Aikins’ leadership of the ship’s company.

“One of the decisions I made was to try to reduce the exposure of the crew to the human remains coming on board,” said Aikins. “Because, as you can imagine, it’s pretty horrific. You’d see stuff. You’d see kids’ toys. It was hard.”

Even so, Aikins couldn’t shield his crew, or even himself, from the lasting effects of this mission.

Living with PTSD

“A lot of the sailors suffered afterward with PTSD,” said Aikins. “PTSD was not something the Navy was used to dealing with, at all.”

He remembered being personally unaware of this condition at the time. “I didn’t even know about PTSD,” said Aikins. “I had no idea.”

His first inkling that something was amiss was when a few crew members asked to return to shore before the mission was over. This perplexed Aikins. “I didn’t understand,” he said. “But I was compassionate.”

However, over time, more sailors were clearly manifesting fallout from their work on the recovery effort. “It all happened later,” Aikins said. “I knew we had to do something because I saw my sailors suffering.”

He recounted how greater sensitivity to military and navy culture was needed in the support offered to the crew. “That was one of my big pushes afterward,” said Aikins of his advocacy for appropriate help for sailors post-Swissair.

Aikins seeks help

Aikins was struggling too but, with “no reference point” for what he was experiencing, he “just carried on.” This went on for years.

“I had some issues and I had no idea what was wrong with me,” Aikins said. That was until he was overcome with emotion one morning when getting dressed for work. “All of a sudden, it just wasn’t right,” said Aikins.

The father of four wrestled with believing that what he went through “wasn’t that bad,” especially in comparison to others like soldiers or firefighters.

Additionally, Aikins needed to work through his own shame associated with these struggles. “I was a captain of a ship,” he said. “It was embarrassing.”

Nevertheless, Aikins sought help.

In doing so he learned that “psychological trauma” is cumulative. “What I understand now is, apparently, those things all kind of add up,” Aikins said. “And this is the thing that pushed me over the top. … That was really instructive. That was really helpful.”

Life improved “dramatically” for Aikins and now, 25 years later, he sees how a foundation was being laid through his vulnerability.

Unbeknownst to him at the time, the way was being prepared for a deeper conversion several years after his early retirement from the Navy in 2003.

Seeds of conversion and change

Aikins recognized a severe mercy in being broken through his experience.

“It took my pride away,” he said. “I was a prideful, swashbuckling naval officer. And it took the wind out of my sails, which is good.”

The 64-year-old elaborated on how these circumstances cultivated an openness in him and a recognition that he needed God.

“We’re the strongest when we’re weakest,” said Aikins. “But we can only be strong if we admit we’re weak, if we recognize that weakness. And certainly nothing in my life [up] to that time would have had me contemplate any kind of weakness in me. I was just a really hard-charging naval officer. That’s what I was. That’s what I did. And unless we have an awareness of our fragile and flawed humanity, I don’t think we can be open to a relationship with Jesus.”

Aikins’ role as on-scene commander brought about additional transformation in his life, including his approach to others. “It softened my attitude toward people,” he said.

The Halifax resident acknowledged that, prior to this, he would have treated others as he treated himself, with a type of hardnose expectation to endure without complaint.

“That was, I think, really important in softening me toward trying to understand the burden that others carry,” said Aikins. “That was a real huge lesson for me.”

Since this time Aikins’ history has aided him in journeying with others. This has included a colleague who is growing in openness to faith partially because of Aikins’ shared experience with PTSD. Aikins said this individual knows “that he’s got a kindred soul” to speak with.

The ability to talk about one’s challenges has been vital for Aikins’ friend. Others, however, were not so fortunate.

‘A terrible mistake’

Looking back, Aikins proposed that there was a critical missed opportunity that could have assisted the crew in having better outcomes. “Our spiritual care was lacking,” he said. “And that, I think, exacerbated the PTSD issue.”

“Any ship that’s involved in something challenging like that needs to have good spiritual support,” said Aikins. “That’s absolutely critical.”

He explained that it was typical at that time to have a military padre, the equivalent to a chaplain, onboard as part of the ship’s company.

However, when it came to the Swissair operation, a padre who was part of an international exchange, and thus entirely new to the HMCS Halifax crew, was assigned to them.

“This was a terrible mistake,” said Aikins.

He noted how a padre is someone with whom the crew are familiar. Accordingly, any member of the ship’s company, regardless of rank, would be comfortable to go to this person to speak frankly and in confidence.

There was no such rapport with a new padre.

Additionally, there were also cultural differences as well as language barriers with the French-speaking crew members.

Aikins stressed that this padre did the best he could under the circumstances. “It didn’t work out great,” he said. “But that wasn’t his fault. It was just that he was put in a terrible situation.”

A need for Jesus, unfulfilled

This acute spiritual lack “awakened an awareness” in Aikins about a new “dimension of faith” he hadn’t thought of before.

This included an awareness that padres have “the ability through faith, and sharing that faith in Jesus, to bring people through very difficult things.”

Aikins recognized how a padre serves a vital role toward those who, “unbeknownst to them, are seeking God.”

“I knew with absolute certainty that a padre — a good padre — could be a game changer in that situation,” said Aikins. “I now realize that what I was sensing was that everybody needs God. But most people, for whatever reason, are not aware of that.”

The crew of the HMCS Halifax met with circumstances that drove home that need. “I think the atmosphere aboard that ship was that there was a lot of people who were aware that they needed God, that they hadn’t before,” Aikins said. “There was an incredible opportunity to spread the word of Jesus on that ship.”

“I wish I had then the faith I have now, because I believe … it could have been very different in terms of helping those people through that,” he said.

The “dint” of Aikins’ leadership, as he had hoped, wasn’t enough to bring his crew through the mission unscathed. Aikins needed Jesus, as did his crew.

Father Mallon’s pastoral experience

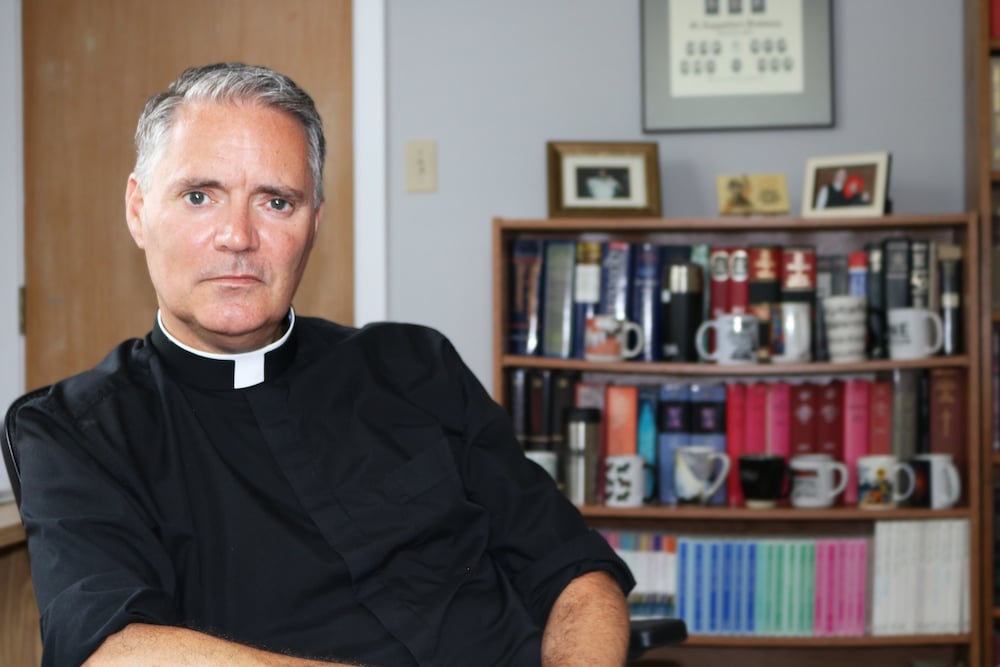

Similarly, Father James Mallon was encountering areas for improvement in the onshore chaplaincy efforts following the Swissair crash.

One of the abiding lessons he and Aikins shared was the importance of nuance both in one’s approach and the spiritual care presented during times of tragedy.

Both Aikins and Father Mallon saw firsthand how it was, perhaps, not enough to offer faith-based ministry. Where possible, such care needed to incorporate the characteristics of relationship: familiarity, intimacy, privacy and accompaniment.

Father Mallon had been ordained for less than a year and a half at the time of the air disaster. When a call went out for clergy to help, he volunteered.

“I signed up. I went and got my security pass,” said Father Mallon. “My first shift was scheduled a few days later.”

Father Mallon explained that the human remains collected on Aikins’ ship were brought to an airforce base in Shearwater, Nova Scotia, for identification, including DNA testing.

He and other chaplains were scheduled to be present at this location to “respond to people in need” because of how “highly traumatic” it was. “We were to be there in a kind of spiritual counseling capacity,” said Father Mallon.

He described how there was “an area marked off for chaplains.” Present at any given time were several chaplains as well as a psychologist. Father Mallon recounted how chaplains came and went. “No one came to talk to us,” he said.

“I felt like an interloper. I felt like a voyeur in some way of grief,” said Father Mallon. “It didn’t sit well with me.”

The 28-year-old grew in his discomfort. This continued until he decided to leave and not return. “I only went once,” said Father Mallon of his shifts at this location.

Once was enough for the young priest to realize that this was an ineffective application of his desire to help.

That said, Father Mallon remained on the list of clergy to be called on if there was a specific request. A possibility for such ministry was with crash victims’ families who traveled to Nova Scotia.

“They may want either to talk to someone or draw upon the services of clergy,” said Father Mallon.

In the following weeks this call did come on behalf of two siblings whose mother perished in the crash.

Authentic chaplaincy

“This was a very different experience,” said Father Mallon of his encounter with the woman’s children.

The young man and woman flew in from the United States to visit the crash site. To honor their mother, the brother and sister had “specifically requested a Catholic priest” accompany them.

“They knew it would be important to their mom,” said Father Mallon.

He met them at the airport and together they all traveled to the crash site near Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia. By the time they arrived, it was dark.

Father Mallon recounted how there was a little nook in the rocks where you could sit down and look in the direction of the crash site. “We just sat in silence. And then I prayed with them,” he said.

After this, all three drove back to Halifax together. The siblings were staying in a hotel not far from the cathedral where Father Mallon was stationed. “I can’t remember how it came about, but we ended up meeting up afterward,” he said. “We had a drink together.”

“They were certainly open to faith and curious about faith and it had value for them,” said Father Mallon.

“That was the exact opposite experience from the Shearwater one,” he said. “This was very profound.”

Father Mallon agreed that chaplaincy during tragic events like the crash of Swissair Flight 111 is important. However, he pointed to the encounter with the bereaved family members as an example.

“That was accompaniment, it was listening, silence, it was prayer and then honest conversation over a pint of beer,” said Father Mallon. “That was authentic chaplaincy.”

The pastor of Our Lady of Guadalupe parish in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, acknowledged the importance of this encounter. Afterall, it helped motivate him to keep his security badge for the last 25 years.

Asked what this ID badge represented to him, Father Mallon said, “It was a significant historic event in the history of our city and province, and I was there. I was a part of it.”

God is with us

Aikins also was part of it, with the long-term effects to prove it.

That said, he knows now that these hardships have borne fruit. This is something Aikins hopes others can find encouragement in for themselves.

“The human condition is that of suffering, and I think it’s just really important for Christians who have been faced with trauma … [to believe] that God can do something positive with that, not just in your life, but in other people’s lives,” said Aikins.

Referring to the lives of the saints, particularly the “heroic struggle” of St. John of the Cross during “the dark night of the soul,” Aikins said that “what got St. John through that” was the knowledge that “God was still there. … That’s, I think, the easiest thing to forget,” he said.

Aikins suggested that while humans can fail to remember that God is present with them in such times, the devil is well-aware of this forgetfulness.

“The Evil One loves trauma, and we don’t think about that,” he said.

God’s light in the darkness

Aikins proposed that amongst the consequences of our fallen human condition are propensities toward greed, lust and jealousy. “Only God can take us out of that condition,” he said of the tendencies related to the Fall. “And it’s the same thing with the darkness of trauma.”

“I think trauma brings out an inner darkness that we have just as part of being human,” said Aikins. “Darkness abhors light, and I think we descend into that darkness in our trauma.”

“It’s finding the hand of God in that darkness,” he said. “God’s hand is there waiting for you to grab him. And that’s the only way out.”

Aikins likened this knowledge about darkness to the psychological tools which assisted him in his recovery from PTSD. He stated that knowing these things in advance are crucial in order to avoid such a path. “If we don’t know that, we’re naturally going to go there,” he said of the darkness related to trauma.

Additionally, Aikins suggested that the Evil One waits in this darkness to bring about despair. Thus, people need to “let the Lord’s light into that darkness.”

“God is light. We do know that,” said Aikins.

He insisted that “even if there isn’t any light now,” individuals can cling to the knowledge that “at some point, there will be light in this darkness.” Therefore, whatever the length of the path to restoration and healing, there is the certainty of God’s light.

“It could take years, but the light can shine in that darkness,” said Aikins.