Carlo Carretto was a leader in the Catholic Action movement in Italy in the first half of the 20th century. An activist on the front lines, he had given all his energy, his whole life, to transforming the world through the implementation of Catholic social teaching. Very much a fighter, a vocal leader, he was a man committed to building a more just Church and society.

But then at the age of 44, he left it all to join the Little Brothers of Jesus in Algeria, following in the footsteps of Charles de Foucauld. All his life an activist, suddenly he became a hermit in the desert. Leaving the active life behind, he embraced the contemplative life, a move so at odds with what we think good Catholics should do in the modern world.

Which is why Carretto’s “Letters from the Desert” (Orbis Books, $18) are so interesting to read because they help put it all in perspective: how the contemplative part of a Christian’s life relates to the active part, how mysteries like the Eucharist relate to what we do, or think we do, for the Church or for society.

For me, it’s the lesson he learned while adoring the Blessed Sacrament in a cave in the Sahara that has long stuck with me — a lesson about faith and about how God saves the Church and the world, not us.

| August 18 – Twentieth Sunday in Ordinary Time |

|---|

|

Prv 9:1-6 Ps 34:2-3, 4-5, 6-7 Eph 5:15-20 Jn 6:51-58 |

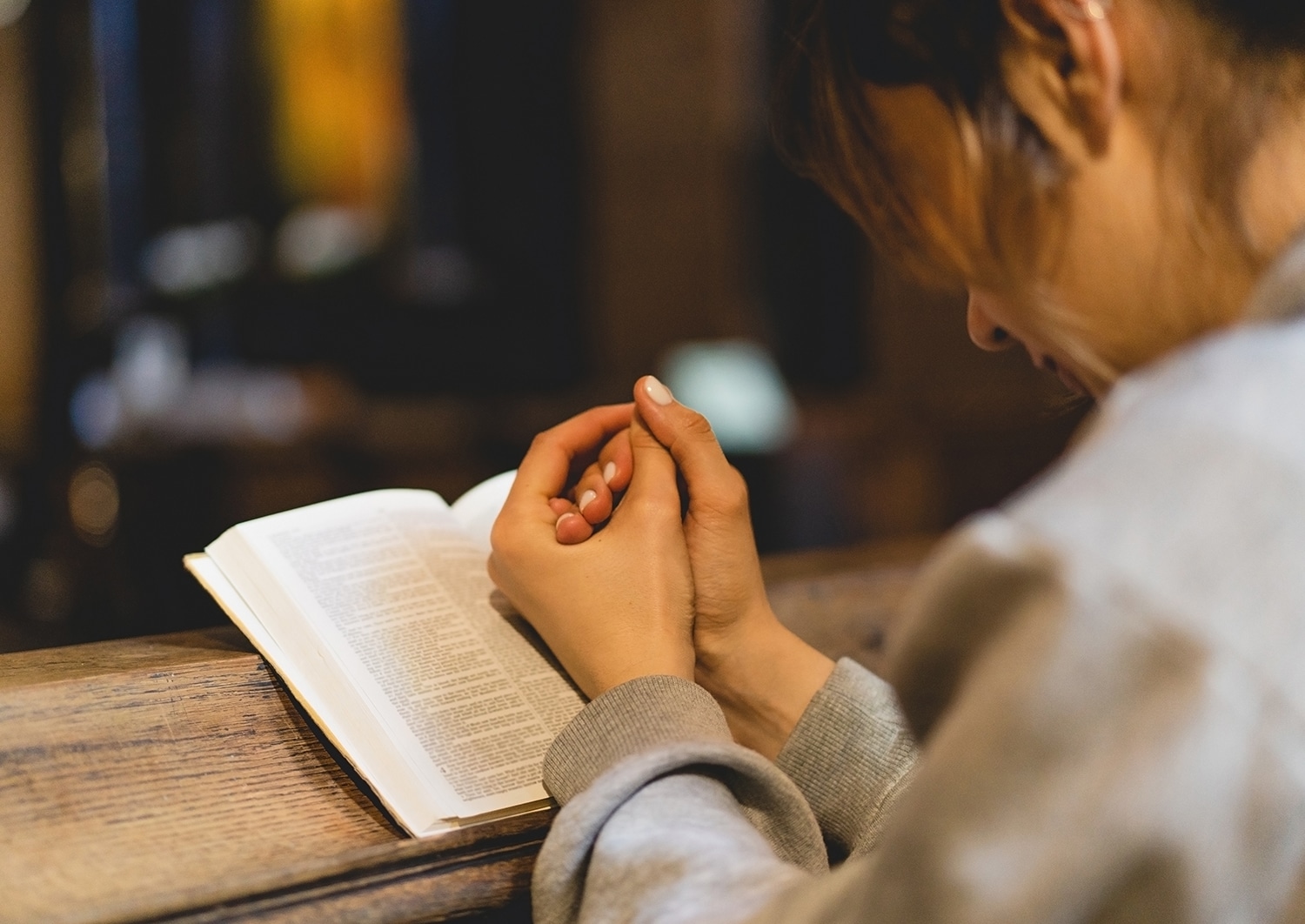

As a novice, he was left alone once, for a week, in a cave in the desert with the Blessed Sacrament. One would think that a sweet retreat, beautiful; but it was, he said, an unnerving experience. “Silence in the desert, silence in the cave, silence in the Eucharist. No prayer is so difficult as the adoration of the Eucharist. One’s whole natural strength rebels against it,” he wrote. “One would prefer to carry stones in the sun. The senses, memory, imagination all are repressed. Faith alone triumphs, and faith is hard, dark, stark.”

What he discovered, sitting there in silence before the silent Host, was how addicted he was to the senses, and then to his own sense of importance — to the idea that what the Church should or could or would accomplish somehow needed his activity. He wrote, “For many years I had thought I was ‘somebody’ in the Church. I had even imagined this sacred living structure of the Church as a temple sustained by many columns, each one with the shoulder of a Christian under it. My own shoulder too I thought of as supporting a column, however small.”

That’s why Carlo Carretto couldn’t bear the silence of the Eucharist, its seeming inactivity. Because he was conditioned to think always in terms of doing something for God. “So convinced were we that the path of action was right, was true.” But things had gotten out of balance for him. Activism became everything and so had pride. The silence of almighty God saving the world and the Church through a silent sacrament: the truth of it mocked his sense of self-importance, his nagging feeling that he needed always to be doing something. But he learned that God didn’t need him at all, that God was not an instrument but that he himself should be the instrument. But that meant he needed to learn to become passive before the Lord before presuming to take up action on the Lord’s behalf. Which was precisely the lesson he found so brutally difficult. “After twenty-five years, I had realized that nothing was burdening my shoulders and that the column was my own creation — sham, unreal, the product of my imagination and my vanity.”

Our missionary role

Now I bring this up, the lesson Carlo Carretto learned in the desert, simply to point out that it’s a lesson we all should learn. As we meditate on Wisdom’s invitation — “Let whoever is simple turn in here” — and as we hear the Lord’s words, inviting us to eat his flesh and drink his blood for the sake of life and eternal life; before we treat the Eucharist like it’s an energy drink, let’s remember that we must first be Eucharistic contemplatives, passive before the Lord, silent in the Eucharist before we dare do anything in his name. Otherwise, we risk becoming merely noisy and proud. We risk making the Eucharist about ourselves and what we are doing — which would be a kind of lie.

This too seems a good thing to think about in this season of Eucharistic revival, the good of becoming Eucharistic contemplatives, the good of being passive before the Lord. Carlo Carretto had to go to the desert to learn this lesson, but you don’t have to. Your parish can be your desert — its quiet chapel, its silent mystery.