“I thirst” is the shortest of the Lord’s last words (Jn 19:28). Short though it may be, it contains unsearchable depths.

“I thirst.” (Jn 19:28)

The Fifth Last Word

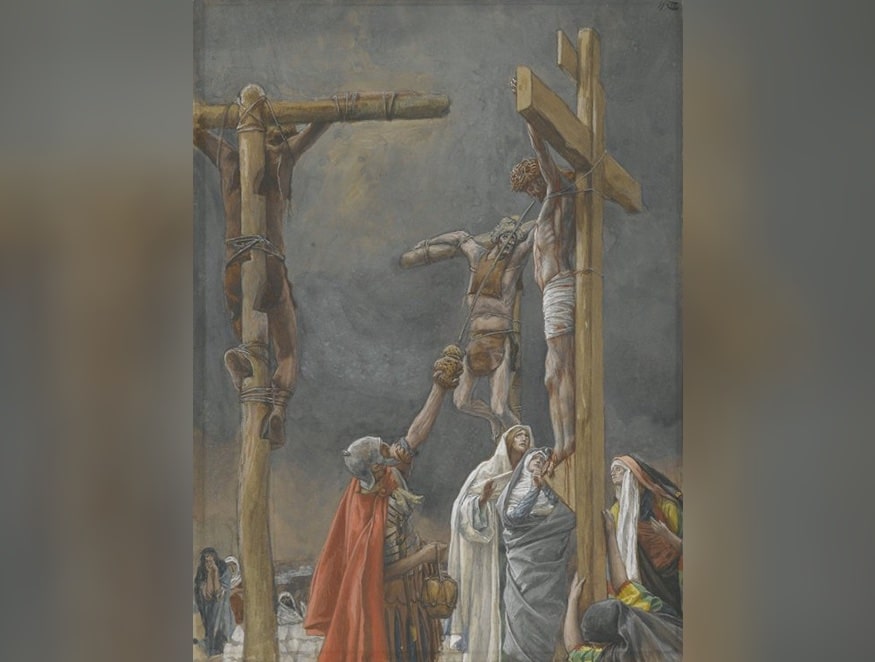

The Lord was telling of his physical thirst on a first and properly literal level. The physical thirst of the Lord was no trivial detail in the Passion story but was foretold in the Old Testament. Psalm 22 tells us his “tongue cleaves to” his palate (Ps 22:16). Psalm 69 is even more explicit: “I am weary with crying out; my throat is parched” (Ps 69:4). When the soldiers at the foot of the cross heard Jesus say “I thirst,” they noticed “a vessel filled with common wine. So they put a sponge soaked in wine on a sprig of hyssop and put it up to his mouth” (Jn 19:29). The soldiers interpreted the Lord’s declaration of his thirst simply on the literal level, and they took advantage of the situation to torment him a bit more. By dipping the sponge into the bowl, they attempted to deceive the Lord into anticipating a drink of refreshing water. Yet, rather than give him some refreshing water, they gave him vinegar to drink. In so doing, they fulfilled the words of Psalm 69: “For my thirst they gave me vinegar” (v. 22).

On a second and more figurative level, the thirst of the Lord revealed something deeper going on in his soul. Today, western people tend to use a rather abstract vocabulary to describe our inward psychological or spiritual states, but the ancient Jews normally described the same inner states with a very physical and earthy vocabulary. An ancient Jew would not simply say, “I am sad,” but would say, “I am wearied with sighing; all night long I drench my bed with tears; I soak my couch with weeping” (Ps 6:7). Similarly, an ancient Jew would not simply say to God “I love you,” but would say: “O God, you are my God — it is you I seek! For you my body yearns; for you my soul thirsts” (Ps 63:2). For the ancient Jews, the language of thirst is the language of love.

Jesus declares his love

Yet, to whom was the Lord declaring his love when he said “I thirst”? Perhaps he was declaring his love to the Father — telling of his burning desire to go home to the Father’s house. Surely, though, the Lord also declared his love for you and me. He was telling us the main reason why he endured all the torments of the Passion. Love “endures all things” Scripture tells us (1 Cor 13:7), and Scripture also tells us that Jesus “loved his own who were in the world and loved them to the end” (Jn 13:1). Why did Jesus die on the cross? He died out of love for you and for me. “God proves his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us” (Rom 5:8).

“I thirst” expresses the full measure of Christ’s love for us. Yet, who could ever plumb the depths of his love? St. Thomas Aquinas says, “No one is able to know just how much Christ has loved us.” For the love of Christ, like his peace, surpasses all understanding (cf. Phil 4:7; cf. Eph 3:19). Though the love of Christ is beyond anything you or I could ever fathom, his love is not altogether hidden from us. God bestows the Spirit of his love upon the saints, and by the light of the Spirit many saints have come to experience for themselves something of the breadth and the length and the height and the depth of Christ’s love for us.

Mother Teresa’s encounter with Christ

One outstanding example is St. Teresa of Calcutta. She has become, by the grace of God, a special witness to the mystery of the thirst of Jesus. At the age of 18, she left her childhood home to join the Sisters of Loretto. Only a few months later, she left her homeland of Albania to become a missionary in India where she eventually made her vows as a sister. The poverty of the people of Calcutta made a deep impression on her.

After 15 years, on Sept. 10, 1946, she was taking a train to make her annual retreat in Darjeeling. During the train ride, she received a special grace — an encounter with Christ — in which he revealed to her personally something of the mystery of his thirst. The grace and the light of the encounter was so personal, and so intimate to her own heart, that she rarely spoke of it to anyone except her spiritual directors. Over the years, however, what was revealed to her very gradually came to light for the world to know.

It seems that was given to her on the train was the grace to understand that when the Lord Jesus said the words “I thirst” from the cross, he was declaring out loud the depths of his love and desire for her personally. His words were a revelation of God’s desire for her being lived out in the heart of Jesus. Yet, his desire for her personally was not a desire for her alone. Amid his passion, Jesus Christ thirsted for each and every one of us personally. What was granted to Mother Teresa, it seems, was to experience something of his thirst for her and for all. She was granted a special sip from the fountain of his love. In the same moment, she also knew she was called to respond. From that moment on, her calling was to spend the rest of her life slaking the thirst of Jesus in return.

How she was to slake the thirst of Jesus was also apparent to her. She was well versed in the teachings of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, and was even named after the Little Flower using the Spanish version of the name. Mother Teresa had come to know well that even the littlest acts of love mean the world to Jesus. Mother Teresa knew that to slake the thirst of Jesus, it was not necessary to do great things. It was enough to do little things with great love. Her inspiration on the train was to slake the thirst of Jesus in the poorest of the poor in whatever little way she could. The poorest of the poor were not few or far away, but all around her in the slums of Calcutta.

To this day, in every house of the Missionaries of Charity throughout the world, next to the crucifix in their chapel, one will find written on the wall: “I thirst.” The words are a reminder that you and I are called to love the one who loved us first from before the foundation of the world. Our calling is to slake the thirst of the one who thirsted for you and me on the cross. Our calling as Christians is to notice the people around us who thirst for love and to slake their thirst in whatever little ways we can. Sometimes, all we can do is smile. Yet, something as little as a smile means the world to Jesus if we do it for his sake. It slakes his thirst in the unloved.

In the last few years of her life, those closest to Mother Teresa began to hear a little more from her about what happened on the train almost 50 years earlier. She opened up a bit about the mystery. In 1993, four years before she passed away, she wrote a letter to all her sisters about the thirst of Jesus. The saints are the best interpreters of Scripture. Here is what she says in the letter:

“For me, Jesus’ thirst is something so intimate — so I have felt shy until now to speak to you of Sept. 10th — I wanted to do as Our Lady who ‘kept all these things in her heart.’ [Jesus’] words on the wall of every MC chapel, they are not from the past only, but alive here and now, spoken to you. Do you believe it? If so, you will hear, you will feel his presence. Let it become as intimate for each of you, just as for Mother — this is the greatest joy you could give me. Jesus himself must be the one to say to you ‘I thirst.’ Hear your name. Not just once. Every day. If you listen with your heart, you will hear, you will understand” (“Mother Teresa’s Secret Fire” OSV, $20.95).