“I was so nervous about having the chalice and paten in my garage,” Jaclyn Warren said. “We have too many kids and too many cats; something’s going to happen to them,” she said.

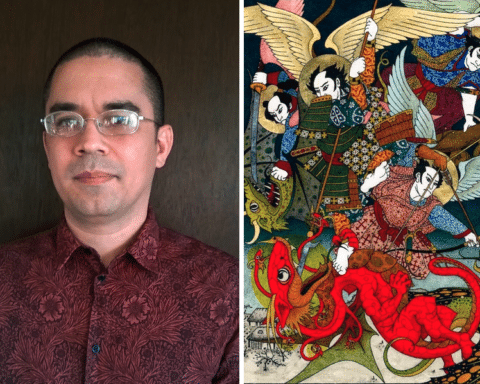

But the precious liturgical vessels survived. They were in Warren’s home, along with a priest in full vestments holding a censer billowing smoke, because she was making sketches for a series of paintings of the North American Martyrs for a high school chapel.

The project, the brainchild of Father John Brown, who commissioned the pieces for Jesuit High School in New Orleans, will show two of the martyred laymen toward the back of the church, and then some of the saints in liturgical dress worshipping along with the congregation, with their vestments becoming more splendid the closer to the altar they are. It’s a huge project, and Warren is working feverishly in between caring for her young children, who, like everyone else in the country, keep getting sick.

Warren, a Louisiana-based liturgical painter and illustrator, said what’s more overwhelming is when she remembers where her work will be displayed.

“It plays on my nerves a little bit. It’s kind of a big deal. People are going to be looking at this for I don’t know how long, maybe after I’m dead and gone, and thinking maybe that nose doesn’t look quite right,” she laughed. “But I know the mission is so important, I can’t get hung up having an artistic crisis.”

Captivating an audience

Mainly, she tries to keep her audience in mind.

“I think of all the boys that are going to be looking at [the paintings of saints]. It’s important that they see them as a source of inspiration and strength, and not just, ‘Look at all these bald guys,'” she said.

She knows from personal experience how an off-putting depiction of a saint can stick with you for years.

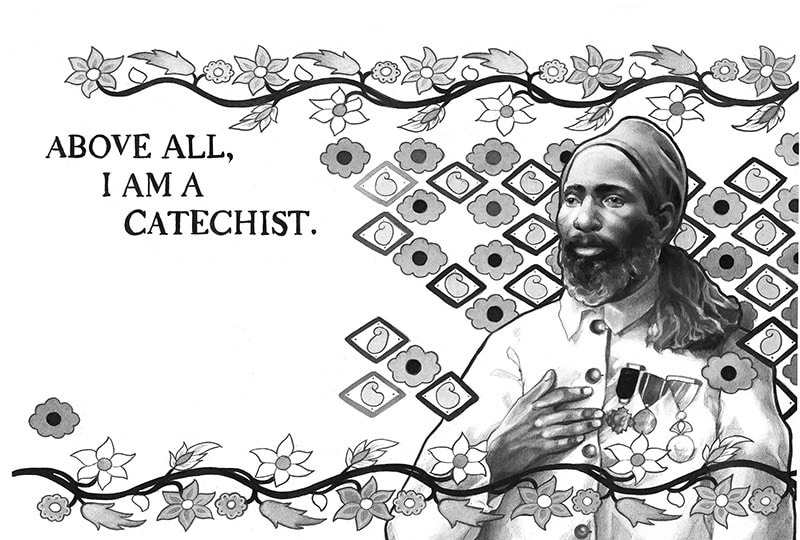

“I remember growing up, I had my book of saints, and Mary Magdalene was wearing this bright pink dress and green eyeshadow, and even at 10 years old I was thinking it was so dated,” she said. She also remembers the Black saints were painted so clumsily, their skin almost looked green.

That was a missed opportunity by Catholic art. Warren grew up loving the saints, but it was despite these illustrations, not because of them; and even though she wanted to be an artist herself, nothing she saw drew her in personally. It never occurred to her that she could be the one to update those unappealing pictures.

“It had already been done. The books have been illustrated; the churches have been decorated,” she remembers thinking. She didn’t see herself as someone who could step up and answer a call.

So when she did study art in high school and then at Savannah College of Art and Design, sacred art was not on her radar.

“I thought, ‘I have to do something that’s going to sustain me. I have this talent; I’ll be a portrait artist. That will make money, and I’ll be secure,'” she said.

An artist’s struggle

But when she attended a summer program at Yale, she found herself the odd man out, ostracized because of her faith and because she made figurative art that wasn’t designed mainly to shock and titillate the viewer. She also noticed that artists who chased the cutting edge of artistic fads might have their moment of fame, but then they were just as quickly forgotten.

“I had to rethink, ‘Is being famous and well-esteemed all it’s cracked up to be?'” Warren said.

She began to wonder if using her gifts simply to earn a living might not be a selfish way to build a life; and so, wanting to move in a more altruistic direction, she began studying art therapy.

That was a struggle.

“Louisiana may be great for arts and culture, but we’re not at the forefront of change,” she said. Locals were suspicious of the idea of art therapy, and it was hard for Warren to find work in her field. She ended up teaching for a few years, and then she married and had her first child.

Art was pushed off to the side. And while she loved being a mother and staying home to care for her family, this wasn’t a happy decision.

“When I was pregnant with my first, I had a lot of naysayers. ‘There goes your sleep! Say goodbye to your life!’ It really scared me,” she said.

She became depressed and anxious, and even avoided thinking about her pregnancy. She thought that, once she gave birth, she’d lose art.

“I thought when the kids go to college, maybe I can have art again. I was mourning, saying goodbye to art,” she said.

God’s assignment

The goodbye did not last long. Warren and her husband now have three children, and it was her husband who urged her to take up her pencils and brushes again. Together they produced the book “Brilliant! 28 Catholic Scientists, Mathematicians, and Supersmart People” (Pauline Books and Media, $25.95), and now Warren is not only thriving as a painter and illustrator, she’s on a mission to encourage others. Warren is co-founder of the St. Louis IX Art Society “to cultivate the sacred arts and promote a culture of Catholic beauty in South Louisiana.”

Warren said that if she could talk to herself of seven or eight years ago, she would say that God deliberately put it on her heart to be an artist.

“He’s not gonna say, ‘I tricked ya! I gave you that desire and that talent, but now you have to do something else,'” she said.

Warren doesn’t gloss over how difficult it can be. There are seasons when the thing you want to do simply has to wait. But if God has called you to something, he’s not going to snatch it away from you.

“I’m on a mission to tell women that,” she said.

Motherhood and intentionality

This idea is what she takes to be one of the main themes in Pope St. John Paul II‘s letter to artists: That God didn’t give artists the desire to create for nothing; and that goes for mothers, as well.

In fact, she thinks having children has made her a better artist, even though she’s so much busier now.

“Having kids has made me more intentional with my time,” she said. She used to work at a leisurely pace, and finish a project when she felt ready; but now she gets right down to business and hits her deadline.

Warren also thinks harder about what children will see and think and feel when they see art. She’s watched her own children respond to pictures of Jesus and the saints, and she keeps their sensitivities in mind when she works out how to depict powerful, potentially alarming scenes from salvation history.

“It’s also made me want to leave a legacy my kids will be proud of,” she said.

Warren wants her kids to be inspired, knowing that their parents worked together to produce good and beautiful work, like the book that pulled her back into making art, and restored her faith that she could still be creative even while caring for small children. Whether they go into a creative field or something else, she wants them to take their individual, God-given gifts seriously.

Just as she wants the young men who see the North American saints on their chapel walls to consider that they, too, might someday become brave and strong and holy, she hopes the children who read the books she illustrates will find them attractive enough to begin to consider the possibility of taking it personally, as she eventually did.

Using honey

Warren takes pains to depict historical figures accurately.

“They look real, a little bald, a little chunky. But my chief concern is mainly beauty, to draw people in. I wish I had realized that much earlier: Beauty can draw people in,” she said.

Warren said she takes inspiration from Bishop Barron’s frequent message that the beauty of art is a powerful tool for conversation and evangelization.

“You’re not going to engage people by hammering them over the head with the truth. You’re going to catch more flies with honey, and the honey is the goodness and beauty we show in artwork,” she said.