Sarah Breisch doesn’t really draw what she wants. Not yet. Breisch, 40, is the mother of eight children, ranging in ages from 17 to 4, and she only recently started showing and selling her work. It’s been a long time getting to this point.

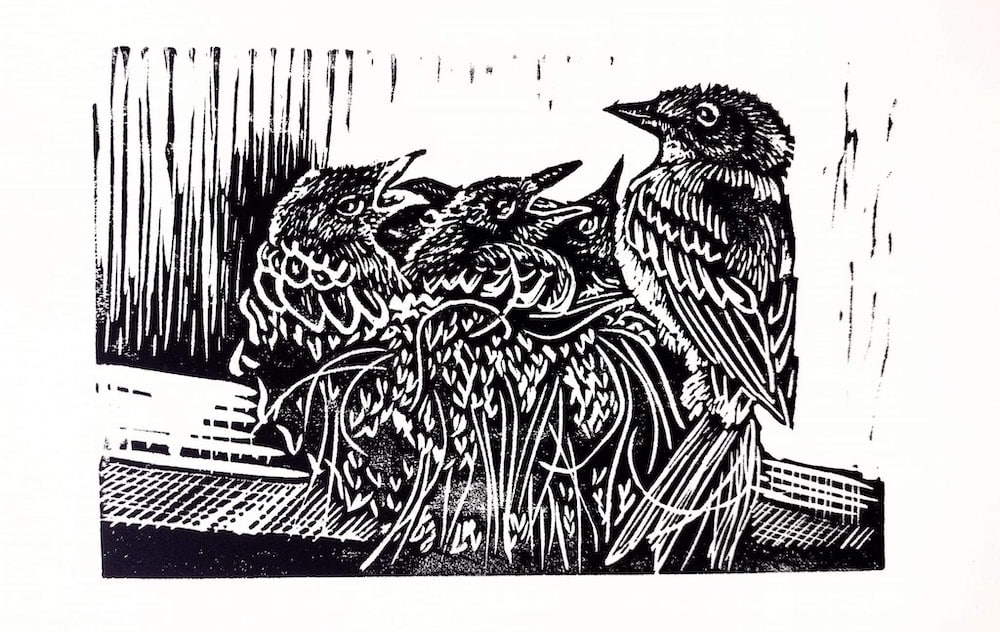

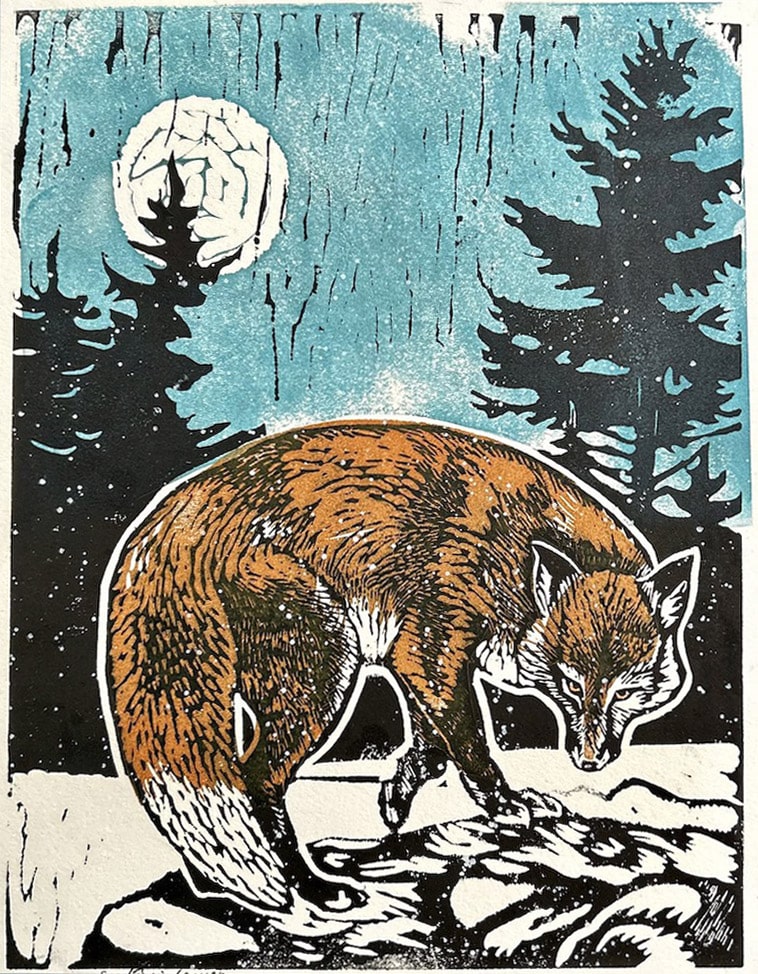

Her artwork — primarily watercolors and lively linocuts of birds and other animals — is vigorous and arresting and sometimes comical. A frazzled mother bird approaches a tangled feathery nest stuffed full of fat, ravenous chicks, in a posture that somehow conveys both love and exasperation. A fox slinks under the moon, casting a knowing, uneasy eye directly at the viewer. A thrush grips a branch between its thorns and sings his tiny heart out into the darkness. They are just animals, but they all seem like someone particular, familiar and very alive.

But Breisch would like to do more. A demanding critic of her own work, she considers her pieces to be mainly decorative, and calls them illustrations without stories. She would like to make art that tells stories, because she has a lot to say.

Breisch had very little in the way of formal art training. Homeschooled from fourth grade through high school, she was free to pursue her own interest in art and artists, and taught herself through museum trips, by leafing through numerous art books inherited from her grandmother, and by using the miscellaneous art supplies she found in her house.

“At that time, art was intensely personal,” Breisch said.

So personal, in fact, that she could hardly stand to show what she had made to other people. And so, although her father, a skilled carpenter with an artistic bent of his own, encouraged her to go to art school when she finished high school, she chose instead to pursue other academic interests and entered the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire.

Inspiration in the Church

It was in the college’s chapel that she first encountered the beauty of the Catholic Church: the beauty of its theology and also of its physical art.

“In the churches I grew up in, art had no place, beauty had little place. Sentimentality and kitsch, what [founder and then-president] Dr. [Peter] Sampo called ‘the banality of received ideas,’ had a huge place. I never set foot in a Catholic church until I went to college, and the moment I did, I was overcome with a sense that this was what I was looking for. And it specifically had to do with the architecture and the art,” she said.

She recalls that the chapel was “not even anything fabulous,” but what there was looked like it had meaning and belonged.

Then the class spent a semester in Rome.

“I came home exploding with joy and inspiration,” she said.

Talents that glorify God

Breisch, whose mother is ethnically Jewish, said, “I knew more than your average kid did about tabernacles and the Holy of Holies and those sorts of things. So when I saw the baldacchino [the ornate bronze canopy-like structure built over the altar at St. Peter’s Basilica], I thought, ‘I know what that is.'”

She thought her father might be open to hearing what she had discovered. But he was not able to.

“He suffered from that sort of mental divide of Protestants [in that] he was artistic and creative, but also an iconoclast, and somehow it felt wrong of him to marry the two,” she said.

As for herself, Breisch had never felt that her faith and her artistic drive were at odds.

“I thought, ‘I glorify my creator through my God-given ability by trying to imitate what I see in nature, because I think it’s wonderful.’ Because it was so private, it was almost like a private meditation,” she said.

Finding time to make art

It was obvious to her that art and faith belonged together — less obvious that what resulted was something that should be shared with other people, even after she decided to join the Catholic Church.

And soon enough, the decision about how to approach her art was taken out of her hands. Shortly after college, Breisch went through RCIA, married and began having children. Over the course of the next several years, she was simply too busy to draw, and too overwhelmed, and didn’t have the money to spend on art supplies. She would make flashcards for her children, or make materials for curriculum when she worked as a teacher, but it was always something utilitarian.

Still, she continued to draw when she could.

“Through my work as a mother, as a teacher, as a child care provider, even when I worked at the jam factory, I would find some ways to do drawing here and there, but it was almost like an act of desperation. I missed doing it so much, but I didn’t feel like I had the time or money to spend on supplies, which is a big deal. I was always trying to do it, because I was desperately out of practice, and I didn’t like how that felt,” she said.

Years went by. Then one day, without much thought, she entered a pen and ink drawing of a peacock into a local contest and won first place. The accolades shocked her. She abruptly decided to dive in and recommit to drawing, specifically to sell. She started showing her work at craft fairs, opened an Etsy shop, and hasn’t looked back.

A desire to do more

A few things have helped sustain and motivate her.

“I have a job that feels stable enough where I feel appreciated; I was at a place where I didn’t have tons of babies in the house, only one, and I was making enough money where I could buy supplies and not starve my children. And my dad was in late-stage cancer. We did lose him that next year, and I really want him to see me selling my artwork, which is something he wanted since I was 12 years old,” she said.

Now that she’s launched her business and has a small but steady stream of sales, she said she feels a new frustration: Not the pent-up frustration of not being able to draw, but the frustration of having to focus on artwork that sells well rather than on new media and experimental pieces that express more personal ideas — ideas that she now feels more ready to share with the world.

| SEE MORE OF SARAH’S ART |

|---|

|

Visit Sarah Breisch’s Etsy shop, Rabbitdogfinearts, where you can view and purchase her paintings and linocuts. |

“I feel like there’s too many things and not enough time. I would like to try all the things, all the styles, all the media,” she said.

“But I’d rather go deep than wide. I’d like to incorporate more religious themes in my work and tell some of those stories. More than likely, [I’d depict] something from the Old Testament, because that’s where my heart is,” she said.

Permission to create

Breisch said that, if she had a motto, it would be “integration.”

“The thing I hate most is compartmentalization. I can’t stand it when people try to make a divide between body and soul, as I saw so much in my Protestant upbringing, and when people feel like they can’t integrate themselves and have unity in their lives. I want very much to be able to integrate my faith into my artwork,” she said.

Breisch knows that freedom to integrate doesn’t come naturally or easily for many people.

“I know, as a busy working mother, the support I need is for people in my life to tell me it’s not selfish for me to take time to do this work,” she said.

She laughed and recalled that it’s not as if she retreats to a solitary studio to draw, isolated from her family for hours at a time. She tends to work at one end of the dining room table while her children crowd the other end with projects of their own.

But even so, Breisch said that she and all parents, but specifically mothers, artists and otherwise, tend to struggle with giving themselves “permission to do things that don’t feel eminently practical but make us better people.”

“It’s kind of a Martha and Mary question. Can I sit down and do this? It’s gonna make me feel good, and make my kids remember that this is the kind of thing their mother did. Or will they remember her running around being frustrated and doing laundry?” she said.

Forging ahead

Breisch has been working as a family support specialist for a local agency for five years. Part of her job is visiting families in their homes, building relationships with them and helping them discover “they can be their own best resource,” she said.

She does see some overlap between how she approaches her job and how she approaches her art.

“The thing you most often hear from parents who have voluntarily enrolled is, ‘I want to do better for my child. I don’t want them to have the same childhood I had,'” she said.

She describes their struggle in epic terms, like a hero facing a dragon and making a new world order for the sake of their child.

“Any creative act is also a type of epic journey,” she said. “Any time I set out to undertake some new image I want to create, there is all this self doubt that comes in the way. I don’t know how to do this; I’m not that good; no one will like this; I’m selfish; it’s not important. When I’m able to face that and reason through it, and understand that creating beautiful things is inherently good, and that it has brought a lot of joy into my home — and my children, in particular, are supportive of me — I’m able to forge ahead and create something new.”