“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your heavenly Father, for he makes his sun rise on the bad and the good, and causes rain to fall on the just and the unjust.

“For if you love those who love you, what recompense will you have? Do not the tax collectors do the same?

“And if you greet your brothers only, what is unusual about that? Do not the pagans do the same?

“So be perfect, just as your heavenly Father is perfect.”

— Matthew 5:43-48

Love our enemy?

Sometimes we can’t even stand a family member, neighbor, fellow parishioner or coworker who can be so … so … Well, you know how certain people can be.

Pray for those who persecute us?

Yes, many people worldwide face persecution but some of us — thanks be to God — don’t even come close to that. Still, we get picked on, or made fun of, or gossiped about. Does the prayer “Dearest Lord, keep those jerks far away from me” count?

It seems Jesus upped the ante on what was required. In the Old Testament, it was: Love neighbor; hate enemy.

That’s mostly doable.

The Lord demands

In the New Testament, we have: Not just tolerate enemy, or quit whining about enemy, or refrain from getting back at enemy, but also love him or her.

Seriously? Impossible!

Oh, sure, “I have the strength for everything through him who empowers me” (Phil 4:13). But not loving our enemies, right? Clearly, not that. There must be a loophole. What we need is a Scripture scholar-theologian who’s the equivalent of a top-notch contract lawyer. Someone who can do some word-nuancing here.

No such luck.

Here’s part of what A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture says on this:

“For the [Old Testament] and Rabbis, the ‘neighbor’ is the Israelite. For Our Lord the word admits no exception. ‘Jesus was the first to teach mankind to regard everyone as a neighbor and to love him.’

“Our Lord recommends not tolerance but positive beneficence. … In this we shall be in the likeness of God — demonstrably his children — because he, with his sun and rain, feeds the lands of friends and foes alike.

“If we refuse this, in what are we superior to the despised publicans or the pagans? If we salute only those in our clique, what generosity is this? …

“Our Lord refuses to set bounds to this ideal. The children are asked to aim at the completeness of their spiritual capacity. When, in their measure, they achieve this they will be like their Father who possesses (though he eternally and of necessity) the fullness of his being.”

Short version: Everyone is our neighbor. Everyone is to be loved. We’re to pray for all those people who harms us or even just irk us. This is the ideal. The closer we get to it, the closer we get to being like God.

Well, rats. It appears there is no escape clause. No wiggle room. No extenuating circumstance.

What to do

That’s the what and the why. As to the how — here are a few points to consider:

1. It’s a good deal. Sign it. This doesn’t benefit just the other guy, the one we’re to love and pray for. It benefits you. It’s how you can grow spiritually. But as is often the case, that growth can be painful. It can take time and effort and sacrifice and practice as you move closer to becoming the “you” God created you to be.

2. You’re still allowed some hating! The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains: “The teaching of Christ goes so far as to require the forgiveness of offenses. He extends the commandment of love, which is that of the New Law, to all enemies. Liberation in the spirit of the Gospel is incompatible with hatred of one’s enemy as a person, but not with hatred of the evil that he does as an enemy” (No. 1933). So, you’re on solid ground with “love the sinner, hate the sin.”

3. “Witness” and “martyr” are in your job description. Again to the Catechism: Forgiveness “bears witness that, in our world, love is stronger than sin. The martyrs of yesterday and today bear this witness to Jesus” (No. 2844).

You may not be subject to major-scale persecution, but even all those really pesky things others do around you, or do to you, can give you an opportunity to be an itty-bitty martyr.

Christ’s command isn’t to — using a 21st-century expression here — “Suck it up, buttercup,” but to pray for the ones who are doing you wrong. And, by that, to become more Christlike. “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do” (Lk 23:34).

4. Holiness can have a sneaky, “gotcha” angle to it. That major politician you can’t stand? The folks who have such disregard for human life? The dictator threatening world stability? The pornographers? The abusers? And on and on to the more personal level for you. The spammers? The people behind sales-pitch robocalls? The identity thieves and computer hackers? The whack jobs on the freeway?

Don’t wail and gnash your teeth. Don’t curse them. Not any of them. Pray for them. That’ll learn ’em.

Your prayers can influence their turning away from what they’re doing, if only infinitesimally now. Just the slimmest hair of the 180 degrees of conversion. Of coming to accept the wisdom the Holy Spirit is offering them. Of the mercy Jesus is ready to shower down on them. Of the love their Heavenly Father is even now giving them.

5. Look in the mirror. Step into the confessional. As the cartoon possum from a mid-20th-century cartoon strip, Pogo, noted: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” How am I causing others to “hate” me? How am I “persecuting” them? Who, despite that, is loving me and praying for me?

And what am I going to do with those same gifts the Holy Trinity is offering me?

Bill Dodds writes from Washington.

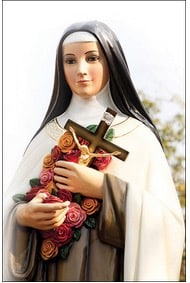

| Trapped in the cloister with your ‘enemy’ |

|---|

|

There are some people who can — literally and frequently — try the patience of a saint.

Take, for example, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, the Little Flower, driven a little crazy by a fellow nun. In the cloister. In the chapel. In the garden. No escape! Here’s how she tells it in her autobiographical “Story of a Soul” (Manuscript C, Chapter 10): “There is in the Community a Sister who has the faculty of displeasing me in everything.” In that woman’s ways, words and character: “Everything seems very disagreeable to me.” But, Sister Thérèse told herself, “Charity must not consist in feelings but in works.” So “I set myself to doing for this Sister what I would do for the person I loved the most.” This meant each time their paths crossed “I prayed to God for her, offering him all her virtues and merits.” (She figured it pleased God for her to mention what a good job he had done creating that nun.) But … She wasn’t “content simply with praying very much for this Sister who gave [her] so many struggles.” “I took care to render all the services possible, and when I was tempted to answer her back in a disagreeable manner, I was content with giving her the most friendly smile, and with changing the subject of the conversation.” (No arguing but sometimes … diverting.) The kicker here?  The fellow community member “was absolutely unaware of my feelings for her … and remained convinced that her character was very pleasing to me. One day at recreation she asked in almost these words: ‘Would you tell me Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus, what attracts you so much toward me: Every time you look at me, I see you smile?'” It was, she writes, “Jesus hidden in the depth of her [that nun’s] soul; Jesus who makes sweet what is most bitter.” But how did she answer that nun’s question? “I was smiling because I was happy to see her (it is understood that I did not add that this was from a spiritual standpoint).” Spiritually, glad to see her. Personally, not so much. |