The waters of the Straits of Mackinac between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan present themselves in beautifully variegated blues. Dark indigo, rich cobalt and bright turquoise greet the passenger ferries as they sail toward the pebbled shoreline of Mackinac Island. As the boats near the docks, the well-kept, sloping green lawn of Marquette Park comes into view. There, in stoic dignity, stands a tall, handsome bronze statue of the man for whom the park is named. The ferry passengers generally ignore it, for the fudge shops beckon.

By the time he took charge of the island’s Catholic mission, Father Jacques Marquette had been serving in New France for five years. Born to a noble family in 1637, Marquette had left his hometown of Laon for the Jesuit novitiate in 1654. Spiritually speaking, this was a golden age for French Catholicism. The lives and reforming zeal of figures like St. Vincent de Paul, St. Louise de Marillac and Abbé Jean-Jacques Olier inspired profound devotion, while the exploits of Jesuits serving in the New World aroused intense interest in the mission field. Marquette caught the fever. He arrived in Quebec in 1666, and after serving at Trois-Rivières, Sault Ste. Marie and Chequamegon Bay (near today’s Ashland, Wisconsin), he arrived on Mackinac in 1671.

A small, reconstructed bark chapel stands to the west of the Marquette statue. It is the only other significant reminder of the island’s role in the French effort to evangelize the region. No one seems to know exactly where the mission stood, and anyway it lasted only a year on Mackinac — the soil was bad and the game limited — before Marquette and the Christian Hurons who were with him moved to the placid mainland harbor a few miles to the west. This new mission, where the town of St. Ignace, Michigan, stands today, prospered, but Marquette would not serve there long. He was soon assigned to a different kind of mission: finding and exploring the rumored great river to the west, the river called by the natives Mississippi.

There was a time in American history when every schoolchild — certainly every Catholic schoolchild — was taught that story, just as they were taught the stories of Champlain, De Soto, Coronado and the other adventurers who made the land that would one day become the United States known to their fellow Europeans. Those stories were not always taught fully or fairly. The violence that accompanied them was too much downplayed, Native American points of view too much ignored. But there is little in the story of Father Marquette’s peaceful explorations for which to apologize — and much to inspire American Catholics.

The same is true for America’s other great peacemaking priest-explorers, among whom Francisco Garcés and Pierre-Jean De Smet stand out for their charity and humanity. As America prepares to celebrate its 250th birthday, their heroic stories deserve to be retrieved. We see in their narratives from not so long ago what pre-Christian societies looked like — their virtues and beauty, on the one hand, and their vices and ugliness, on the other. We also see how a commitment to share the Gospel played out on the American frontier when accompanied by the profoundly Christian tenets of self-sacrifice, mercy and equality before God.

Jacques Marquette: Down the Mississippi by birchbark canoe

Father Marquette left St. Ignace with Louis Jolliet — a Quebec-born former seminarian and experienced voyageur — and five other Frenchmen on May 17, 1673. Their objective, in Marquette’s words, was “to visit the nations who dwell along the Mississippi River.” Precisely who those nations were, what that region was like and where the river went they did not know. The Mississippi might flow west to the Pacific Ocean or Gulf of California. That would be the happiest outcome, for the French, like their European rivals, wanted badly to find a water route across the continent. Or it might flow south, to the Gulf of Mexico. Whatever the case, they needed to document everything about the river and to win the friendship of the people who lived along it.

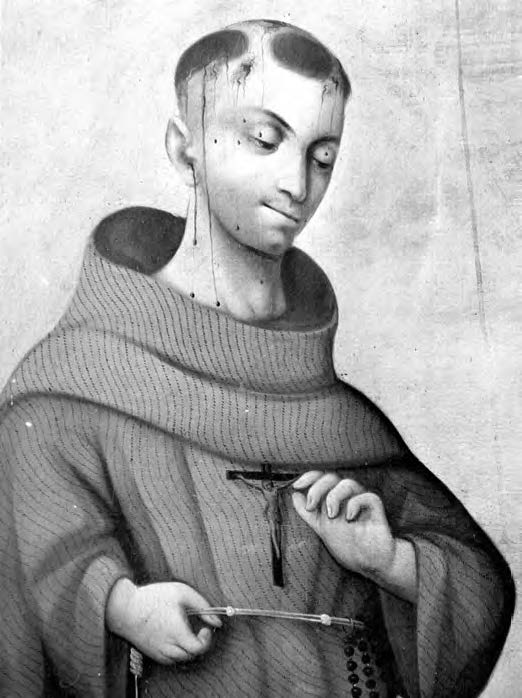

That was the geopolitical point of view. For the earnest and energetic Marquette, it was even more important to preach the Gospel to unreached native peoples. After all, that was the entire point of the Jesuits’ enterprise in New France, and one for which many of their number had died — Father Isaac Jogues, for instance, whose excruciating torture by, escape from, return to and ultimate martyrdom at the hands of Iroquoian-speaking tribes was well known throughout the France of Marquette’s youth. It says much about the era that the grisly end met by Jogues and the rest of the North American martyrs, including Jean de Brébeuf, only increased the desire of passionate priests like Marquette to come to the New World.

Traveling in two birchbark canoes, the Marquette-Jolliet expedition paddled to Green Bay along the northern shore of Lake Michigan. From Green Bay, the men ascended the Fox River to Lake Winnebago. Two Miami guides escorted them from there to the Wisconsin River. Here, Marquette wrote in his journal, they left east-flowing streams “to float on those that would thenceforward take us through strange lands.” The west-flowing Wisconsin took them through a beautiful, rolling panorama filled with tall trees, grassy prairies and shaggy, massive “cattle” — bison — to the Mississippi. Marquette was a keen observer of the landscape, and it is worth reading his journal simply to get a glimpse of how he and his companions experienced the Great Lakes and Mississippi River Valley before those regions were transformed by Europeans.

The expedition’s encounters with Native Americans were sometimes as inspiring as the landscape. On June 25, Marquette and Jolliet entered a village of Illinois Indians, not at all sure that they wouldn’t be killed on the spot. They were instead treated as honored guests. “How beautiful the sun is, O Frenchman, when thou comes to visit us!” said an old man who greeted them at his cabin. The “great captain” to whom they were next taken repeated the sentiment. He also requested — after Marquette explained that among the reasons for their journey was that God had sent him “to make Himself known to all the peoples” — that Marquette “have pity on me, and on all my nation. It is thou who knowest the Great Spirit who has made us all. It is thou who speakest to Him, and who hearest His word. Beg Him to give me life and health, and to come and dwell with us, in order to make us know Him.”

We have only Marquette’s word, of course, that such words were spoken. But, perhaps surprisingly, there is little reason to doubt it. Although contemporary scholars tend to downplay the fact, openness to Christian teaching about God and the supernatural world was not infrequently encountered by early American missionaries. So was another Illinois practice reported by Marquette. “When one speaks the word ‘Illinois,'” he reported, “it is as if one said in their language, ‘the men’ — as if the other savages were looked upon by them merely as animals.” The same was nearly always the case across language groups continent-wide. The idea that there was a trans-tribal or transethnic human nature — or, better put, personhood — common to all homo sapiens seems not to have been held by, or perhaps to have been an idea even available to, America’s aboriginal peoples.

Having met several other native tribes as they continued downstream, not all of them as warmly welcoming as the Illinois, and having ascertained that the Mississippi clearly flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, the Marquette-Jolliet expedition, fearful of Spanish capture, turned around at the Arkansas River. The men were back in Green Bay by the end of September. With their 2,500-mile journey of discovery, they became the first Europeans to map the northern Mississippi River and prepared the continental heartland for deeper French penetration.

Marquette again led the way. Although he was suffering from a debilitating gastrointestinal disorder, he left Green Bay in November 1674 to fulfill his promise to the Illinois that he would return to instruct them about the Great Spirit. Winter trapped him in today’s Chicago, where he and two voyageurs endured a miserably cold and damp three months in camp. At the end of March, the ice finally broke. A little while later, Marquette planted the cross in the village of Kaskaskia, located along the Illinois River between today’s Peru and Ottawa, Illinois. Although thousands of Illinois crowded around to hear his preaching, his health would not permit him to stay. Marquette died May 19, 1675, while returning to the Straits of Mackinac and was buried by his two companions on a hill near Ludington, Michigan. Two years later, a band of Christian Ottawa Indians disinterred his body and brought it to the mission of St. Ignace. A small monument to Marquette stands there today, little visited and utterly incongruous with his significance.

Francisco Garcés: Crossing the Sonoran Desert

Enthusiasm for the missions was a Europe-wide phenomenon during the pious 17th century. Eusebio Kino was born eight years after Marquette in the Italian Tyrol. Like Marquette, he entered the Jesuit order as a young man and soon conceived an intense desire to be a missionary. Sent to Mexico City in 1681, the energetic, handsome, charming priest went on to plant two dozen missions in Baja California, Sonora and today’s Arizona before his death in 1711. He was declared “Venerable” in 2020. But Kino, who spent little time within the borders of today’s United States, is not our subject here, but rather his most able successor at the remote mission of San Xavier del Bac, a Franciscan friar named Francisco Garcés.

A native of the Spanish province of Aragon, Garcés arrived at San Xavier, located a few miles south of Tucson, in 1768. Over the next eight years he would undertake a series of incredible journeys — the Spanish called them entradas — into the unknown (to Europeans, at least) lands to his north and west. No less than Marquette, he bequeathed to us a precious documentary record of the lands he discovered and the Indians he encountered. Like Marquette, he also left a legacy of peaceful intercourse with and high respect for the Southwest’s native peoples.

Garcés’ first two entradas took him north to the Gila River. Working his way westward, he discovered from the friendly peoples who lived there — peoples known today as the the O’odham and Piipaash — that there was established trade and communication with the natives living along the California coast, where his acquaintance and fellow Franciscan friar Junípero Serra had recently begun to establish missions. This was important, for the Spanish did not know of an overland route to Alta California from New Spain’s northwestern frontier — today’s Sonora and Arizona.

Garcés therefore set off to find one. In summer 1771, traveling with few supplies, no other Spaniards, and native guides whom he engaged along the way, he picked his way by muleback across the blazing, bone-dry Sonoran Desert until he arrived at the junction of the Gila and Colorado rivers. He was greeted by a man the Spanish knew as Salvador Palma, powerful headman of the Quechan Indians that controlled the area. Against the advice of his friendly hosts, Garcés proceeded westward through even more inhospitable country until he spied the mountain chain that he figured, correctly, stood between him and the coast.

Three years later, Garcés repeated the feat, this time as the chief guide in an official expedition that included 20 soldiers led by a frontier military official named Juan Bautista de Anza. Surviving largely, if only barely, on water found in remote mountain tanks, the Anza Expedition eventually found its way from the Spanish presidio at Tubac, Arizona, to Yuma, to Mission San Gabriel outside today’s Los Angeles, where the gaunt, dirty and bedraggled men were hailed joyfully by four friars dressed in rags. Garcés celebrated Easter 1774 with St. Junípero Serra at Mission San Diego before returning to San Xavier del Bac.

The achievement of the Anza Expedition led Spain to organize another in 1775. This time, Anza would lead nearly 300 men, women and children to Monterey and San Francisco to become the first true European settlers of Alta California. Garcés left that expedition at Yuma. From there he embarked upon a truly extraordinary solo journey of exploration that made much of what we know as the American Southwest newly legible to European eyes.

His goal was to reconnoiter a better route both from Sonora to Monterey and from Monterey to New Mexico. Over the next 10 months, he rode down the Colorado River to its mouth, then upriver to the vicinity of today’s Laughlin, Nevada (which state he was the first European to enter), then across the unforgiving Mojave Desert to San Gabriel Mission, then into California’s great Central Valley through today’s Bakersfield, then back through the Mojave and northwestern Arizona to the Grand Canyon (where he made a frightening descent into the canyon to visit the Havasupai who lived, then as now, near the famous falls that bear their name), then further east to the Hopi village of Oraibi, before finally returning to San Xavier del Bac. That journey was about as long as Marquette’s to the Arkansas River and back — but even lonelier and more dangerous.

No less than Marquette, Garcés typically encountered both receptiveness to the Gospel (he found that a banner showing the Madonna and child on one side and a man suffering the torments of hell on the other did wonders to communicate his fundamental message) and lifesaving hospitality (he often carried little if any food in his baggage). Native hospitality was not even reserved solely for humans. One day, his mule became stuck in a mudhole. The Cocopah Indians with whom he was staying “all ran to help him, took him out in their arms, and carried him to the fire to get warm.”

Garcés’ diary is filled with such heartwarming incidents. But there was also plenty of darkness. Along the Colorado River, for example, Garcés encountered a band of Chemehuevis who had with them two Halchidhoma girls taken as slaves. Slavery was practiced throughout native America, and although it was illegal, Spaniards on the frontier abetted the trade by frequently purchasing and keeping slaves themselves, a practice that churchmen like Garcés spent much time and ink exposing and criticizing. As for the Halchidhoma girls, Garcés traded a horse for their freedom.

Intertribal warfare was as endemic as intertribal slavery. As humble as he was hardy, Garcés had a special talent for winning native trust and friendship (one of his fellow friars said that Garcés was “so well suited to getting along with the Indians and going among them that he seems to be very much like an Indian himself”), and wherever he went he attempted, sometimes successfully, to broker peace deals. He dreamt of planting a dozen or more new missions in today’s Arizona and southern California not only to save native souls, but also to extend what he saw as the manifest blessings of Spanish civilization — civil peace foremost among them.

It was not meant to be. Broken Spanish promises, imprudent military leadership and Quechan jealousies led to an uprising at Yuma in July 1781 in which Garcés and three other friars, along with 127 other Spaniards, were killed. The monument to Garcés that stands along the Colorado River in front of St. Thomas Indian Mission today is more impressive than the one honoring Marquette in St. Ignace. But it is even less visited.

Pierre-Jean De Smet: Mediator between clashing civilizations

In “Beyond the Devil’s Road” (University of Oklahoma Press), the biography of Garcés I published last year, I argued that Garcés’ epic 1775-76 entrada was unparalleled in the annals of American exploration. I would now amend that claim to make an exception for the travels of Pierre-Jean De Smet, who roamed even further than did Garcés without benefit of European companionship or arms — and under equally dangerous conditions.

De Smet was born in Belgium in 1801. Like Garcés, as a young man he was stirred to serve in the New World missions by the zealous appeals of a recruiter, this one working on behalf of the Jesuits. In 1821 he left, against the wishes of his family, for America.

Unlike Marquette and Garcés, whose likenesses were never portrayed by those who knew them, we know what De Smet looked like: fair, round-faced, athletically stout, uncommonly strong. We also know much more about De Smet’s activities and thoughts, for, also unlike Marquette and Garcés, his extant writing about his explorations and other topics fills multiple thick volumes. Although they can be difficult to find, they make for entertaining reading.

De Smet arrived at St. Louis, then the far edge of Anglo-American civilization, in 1823. There, or rather some 15 miles north in the town of Florissant, where St. Rose Philippine Duchesne and her Sisters of the Sacred Heart were based, he and his fellow Jesuits founded the order’s second novitiate in the United States. Eventually their labors would include also the founding of St. Louis University, but initially one of the group’s main purposes was to found schools for Indian children. This turned out to be more difficult than the fathers had imagined. The real work of evangelization would have to take place further west.

Thus, from 1838 to 1868, Father De Smet crisscrossed the northern plains, the northern Rockies and Pacific Northwest to the tune of some tens of thousands of miles. His purpose was the usual one of a missionary: to preach, teach, succor and serve. He established his first mission among the Flatheads (or Salish) of the Bitterroot Valley in Montana. For decades, these extraordinary Indians had been pleading for Jesuit missionaries; the Faith seems to have been introduced to them by some devout Iroquois — much had changed since the days of Brèbeuf and Jogues — from the east. So much did the Flatheads wish to receive more instruction that four times they sent delegations to St. Louis to request a priest. On one of these journeys, they were traveling with some white men when the party was intercepted by a group of Sioux. The Sioux decided to execute the Flatheads and let the others go, including an Iroquois named Old Ignace whom, because of his dress, they mistook for a European. Ignace, who had done more than anyone to evangelize the Flatheads, would not have it. He stepped forward, revealed his identity, and was slain along with his four native companions. A good book could be written about the unshakeable faith of native Christians like Ignace, for they seem to pop up in every missionary’s story.

De Smet would have happily spent the rest of his life among the Flatheads, but he was too talented and too passionate not to become involved in defending the region’s natives from the rapacity of American traders and settlers and the cruelty and incompetence of the American government. Time and again he wrote letters and treatises exposing the unjust treatment of his Indian friends. Time and again he was prevailed upon by the United States authorities to act as a mediator between government officials and Indian leaders. To make matters worse, time and again he was removed from the frontier by his Jesuit superiors so that he could go on fundraising tours throughout America and Europe. Talent always exacts a price.

One of Father De Smet’s last official acts was to persuade Sitting Bull and his desperate Sioux followers to lay down arms and negotiate the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. Five years later, he died in St. Louis. He had baptized thousands but, like his idealistic missionary predecessors, he believed he had failed to create the space necessary for distinctively Native American Catholic communities to emerge and flourish.

The numbers tell a different story. It is rarely noticed, but today approximately 20% of U.S. residents who identify as Native American call themselves Catholic — the same as among the general population. On some reservations the proportion of Catholics is much higher. Among the Tohono O’odham of southern Arizona, where Garcés labored, it is 80%. There is a strong devotion to the Mohawk-Algonquin St. Kateri Tekakwitha — received into the Church by French Jesuits one year after Marquette’s death — in Indian communities across the country. And the canonization cause for the badly misunderstood Nicholas Black Elk, an Oglala Lakota who knew Sitting Bull well and is now a Servant of God, seems to have momentum.

It is unthinkable that any of that would be the case without the witness and influence of missionaries like Marquette, Garcés and De Smet. As much as they contributed to American geographical and ethnographical knowledge, they ought also to be credited for shaping, much for the better, America’s spiritual landscape. American Catholics can take pride in their legacies of witness.