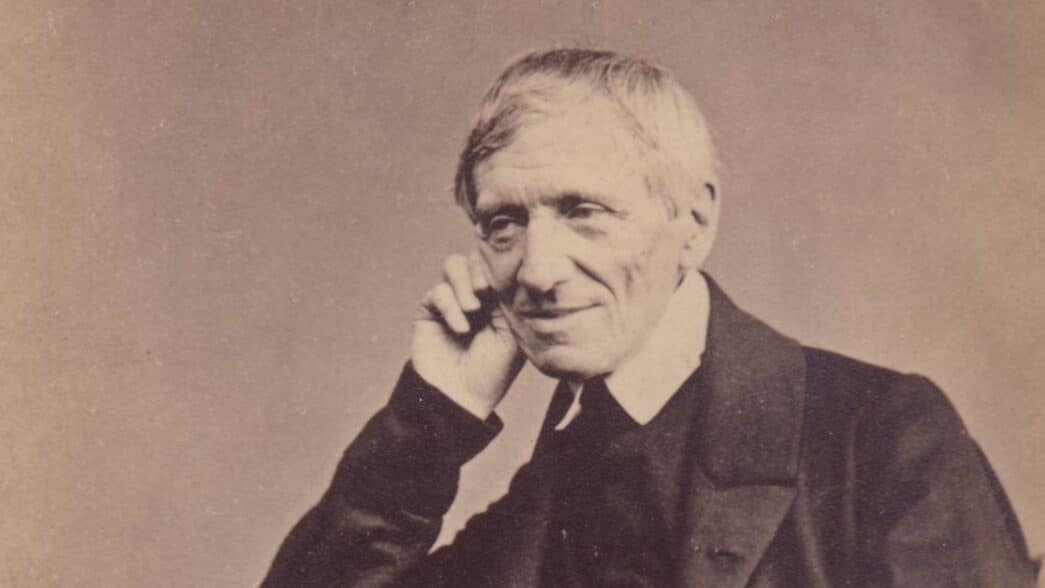

On July 31, 2025, the Vatican press office reported that Pope Leo XIV will soon declare St. John Henry Newman to be a Doctor of the Church. Newman will be the 38th Doctor of the Church and the second Englishman, after St. Bede the Venerable, who was honored by Pope Leo XIII in 1899.

Among the previous 37 Doctors of the Church, several are informally known as the doctor of some characteristic or attribute of the saint. A few examples include St. Thérèse of Lisieux, known as doctor amoris (doctor of love), St. Teresa of Ávila, doctor orationis (doctor of prayer), St. Thomas Aquinas, doctor angelicus (the angelic doctor) and St. Augustine, doctor gratiae (doctor of grace). These are not official designations, but rather epithets that describe some contributions that these saints have made to the universal Church. In this spirit, I suggest the appellation “doctor of development of doctrine” for St. John Henry Newman.

Newman’s profound insight

Perhaps the greatest contribution that St. John Henry Newman made to the Church was his explanation of the development of the doctrines of the Church. Indeed, it is arguable that his most important work is his 1845 book “An Essay on the Development of Doctrine.” Published the year of his conversion to the Catholic Church, the essay accounts for the development of such Catholic doctrines as purgatory and devotion to Mary, comparing their development to less controversial doctrines, such as the Holy Trinity and the two natures of Jesus Christ. Newman’s purpose was to show that doctrine naturally develops over time, as the Church more deeply contemplates the truths of revelation. Thus, it is no more legitimate to reject Marian dogmas because they developed relatively late than to reject the doctrine of the Trinity, which developed earlier.

To make his case, Newman distinguished between doctrinal “development” and “corruption.” The former is nothing more than the articulation of various aspects of the truth of a Christian idea, the fullness of which could not be grasped upon its initial revelation. As St. John put it, the “idea” is fixed once for all time. But various descriptions and implications of that idea take time to germinate, bud and flower as the Church prayerfully considers them. “The idea which represents an object or supposed object is commensurate with the sum total of its possible aspects,” Newman explains. These aspects, however, may “vary in the separate consciousness of individuals; and in proportion to the variety of aspects under which [the idea] presents itself to various minds is its force and depth, and the argument for its reality.” We call this process “development.”

Development is a necessary aspect of Christian theology, Newman argues, because no single expression of a doctrine can possibly account for the depth of its richness. “There is no one aspect deep enough to exhaust the contents of a real idea,” he explains; “no one term or proposition which will serve to define it.” Development is not the emergence of a “new” idea, but rather the fuller explanation of the complexity of the one idea. “One representation of it is more just and exact than another,” he continues. “When an idea is very complex, it is allowable, for the sake of convenience, to consider its distinct aspects as if separate ideas.” Thus, for example, we understand both “ideas” that Jesus is God and that Mary is his mother. It follows, therefore, that the Blessed Virgin is the mother of God. And even from that conclusion, dogmas may (and do) emerge that are necessary correlations of these central ideas.

Development or corruption?

Corruption of doctrine, on the other hand, occurs when a proposed doctrine is not compatible with previously stated dogmas or which substantially departs from the fullness of the Christian tradition. “A false or unfaithful development,” Newman writes, “is more properly called a corruption.” A theological proposition that either contradicts an established doctrine, or cannot be reconciled with a historical articulation of the doctrine, would be a corruption, rather than a development. For example, if one were to say that we are saved by the merits of the Blessed Virgin — admirable as they are — that would be a corruption of Marian doctrine, not its development. This is because it contradicts the received understanding that Christ alone is the redeemer, including the redeemer of St. Mary.

“There is no corruption if (the doctrine) retains one and the same type, the same principles, the same organization,” Newman explains; “if its beginnings anticipate its subsequent phases, and its later phenomena protect and subserve its earlier; if it has a power of assimilation and revival, and a vigorous action from first to last.” As theological tools to distinguish authentic development from corruption, Newman proposes and explains seven “notes” of genuine development: preservation of type, continuity of principles, power of assimilation, logical sequence, anticipation of the future of the doctrine, conservative action and chronic vigor. “An Essay on the Development of Doctrine” is a book-length explanation of these seven notes.

Of course, others may suggest equally applicable epithets for St. John Henry Newman. These might include “doctor of conscience,” with a nod to his “Letter to the Duke of Norfolk,” or “doctor of conversions,” reflecting his great spiritual memoir, “Apologia Pro Vita Sua.” I would not gainsay either of these possibilities. But in a time of theological tension and uncertainty, the greatest gift that Newman has given the Church is his robust defense and explanation of the development of Christian doctrine. St. John Henry Newman, doctor of the development of doctrine, pray for us.