In 1947, on the occasion of her 21st birthday, then-Princess Elizabeth marked it by sharing her own sense of herself and her role as the eldest daughter of the United Kingdom’s reigning king. Speaking “to the whole empire listening” as she toured Cape Town, she said: “I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.” Inviting citizens of the Kingdom and the Commonwealth nations to “join in” on her resolution, she ended, “God help me to make good my vow, and God bless all of you who are willing to share in it.”

Reams and reams of copy have been and are being written about Queen Elizabeth II on her passing, with some suggesting that her death marks a kind of “official” ending to the social dominance of what Tom Brokaw so memorably called “The Greatest Generation” — the one that brought the world through the tumult and horror of the Second World War. In fact, though, Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor was born two years earlier than those counted among what has been called “The Silent Generation” — those who lived through the Great Depression and have been broadly characterized as being quietly faithful, dutiful, optimistic, selfless and unshakeable — a generation able to “keep on keeping on,” as the saying goes, as they worked within socioeconomic and religious systems.

To put it another way, Elizabeth was of a deeply stable generation, serious and pragmatic, part of a demographic trained in keeping the head up and getting on with whatever task was before them, despite difficulties. They reliably kept to the values and considered virtues of their parents: Do your work, go to church, dress modestly, don’t complain, praise others before yourself, mind your manners and smile. And keep smiling.

Simple grace

That steadiness and pragmatism may be why her passing has brought forth such an outpouring of expressed admiration by many people “of a certain age” and surprised curiosity by younger journalists and voices on social media. To a generation raised on bellowing, spittle-flecked politicians and pundits who define themselves by the (quite predictable) stands they take on any given issue, watching snippets of Elizabeth II’s low-key, drama-free stoicism might strike some as dull, unemotive and detached to a confusing, confounding extreme. Did nothing move her? Did she never itch to give a smack down? Telegraphing nothing, giving no arch or sly hints of political leanings in the ways we are used to seeing, what did Elizabeth stand for, after all?

Well, she stood for Britain and the citizens of the United Kingdom. All people in leadership are performers to one extent or another; within this constitutional monarchy, Elizabeth’s role was to be the reliable antidote to the bombastic, to be a sturdy beacon piercing through the occasionally thick fogs of upheaval, change and uncertainty — to not simply react to every whirlwind but to respond to what really mattered, and in due season.

Defined in that way, she stood for stability. If the words “keep calm and carry on” helped to buoy British morale during World War II, then Elizabeth (who trained as an auto mechanic for the British Army in 1944), became the embodiment of the sentiment long before taking the throne. As a 13-year-old sent to live away from her family during the London Blitz, she made a radio address directed toward those children who had been similarly displaced from their homes and loved ones.

“Thousands of you in this country have had to leave your homes and be separated from your fathers and mothers. My sister Margaret Rose and I feel so much for you, as we know from experience what it means to be away from those you love most of all. To you living in new surroundings, we send a message of true sympathy, and, at the same time, we would like to thank the kind people who have welcomed you into their homes in the country.”

Simple words, expressed simply — there are no complicated ideas, here, and no grandstanding — but the sense of solidarity with her contemporaries is offered with the clarity, charity and expression of gratitude to others that would become a constant for Elizabeth in her speeches. Some in the 21st century will dismiss that youthful address as a trifle, but to do so would be missing the point. In the midst of national and familial turmoil, when lives were turned upside down, sparing no one, Elizabeth’s empathetic words made people feel seen, their hurts not just acknowledged but known and shared. While the young princesses’ privations were not exactly the same as those experienced by families pulled apart by great distance, the straightforward sentiments conveyed commonality where it could and did exist, and thus her modest pronouncements were forcefully reorienting and unifying; they said precisely what people needed to hear when their private worlds were collapsing: “You are not alone. We are here, and we are one.”

Possibly that sense of shared hardship was behind so many young women sending their clothing ration coupons to Elizabeth in 1947 so that she might have a proper wedding gown for her marriage to Philip Mountbatten. Doing so was illegal, and the young bride returned the coupons, again with expressions of gratitude, but that so many ordinary people wanted to help someone who really didn’t need it speaks hugely to the relationship Elizabeth had established with the British population well before her coronation.

The queen’s humanity

Her seeming simplicity was the paradoxical source of her quietly powerful presence and her ability to hold on to the people’s affection through seven often tumultuous decades. The only hiccup within the relationship between the queen and her people came in 1997, at the sudden, ghastly death of Diana, Princess of Wales, when Elizabeth failed to “read the room” and remained too silent for too long. Of the reliably consoling queen, no glimpse was given, and no statement released, for five days. Perhaps in unexpected need of consolation herself, the usually empathetic Elizabeth said nothing at all to a deeply shocked and heartbroken nation, until the newspapers — seeing no lessening of shock among the people but only an increasing sense of loss, confusion and grief — demanded it of her. “Where is our queen?” asked one newspaper. Another pulled no punches and got right to the point, blaring in bold caps: “YOUR PEOPLE ARE SUFFERING, SPEAK TO US MA’AM.”

Whether the monarch had simply missed her cue due to shock or had stayed away because she had not recognized the outsized, demonstrative grief (so unfamiliar to the British character), for what it was, Elizabeth got the message. When she returned to London from Balmoral Castle the next day, she had her car stop outside the gates of Buckingham Palace. Accompanied by Philip, she stepped out of the car and walked gravely toward the thousands of bouquets left there by a mourning public, reading the messages and greeting the crowd. As with her adolescent wartime speech, the action had the effect of making the people feel seen, heard, commiserated with and, yes, understood by the sovereign who, it turned out, was a human being as capable of blowing it as anyone.

There is a phrase Jacqueline Kennedy used to repeat as a kind of public-person’s motto, “Never complain, never explain.” That night, Queen Elizabeth made a televised address to the nation, and once again, her words were not remarkable. She neither complained nor explained in obvious ways, but she still managed to show enough of her own humanity and confusion in a way that spoke to what was common between people: “We have all been trying in our different ways to cope. It is not easy to express a sense of loss, since the initial shock is often succeeded by a mixture of other feelings: disbelief, incomprehension, anger — and concern for those who remain. We have all felt those emotions in these last few days. So, what I say to you now, as your queen and as a grandmother, I say from my heart.”

She paid a generous tribute to her former daughter-in-law and then — as always — expressed gratitude to the people. Before her final exhortation that the nation “thank God for someone who made many, many people happy,” Elizabeth invited the nation to “keep calm and carry on,” expressing a hope that, at the next day’s funeral, the nation might grieve together, “for [Diana’s] all-too-short life. It is a chance to show to the whole world the British nation united in grief and respect.”

Because for Elizabeth II, even the transience of tragic death and mourning must not alter the face of Britain before the rest of the world — a calm, steady face, stoic and brave in grief, and unbreakable, much like her own.

The people understood, as was proved the very next morning, when the whole world witnessed hundreds of thousands lining the streets of London, standing with grave, absolute — and absolutely staggering — silence as the flag-draped coffin wended its way to Westminster Abbey. There were no shouts of rage or woe, no surging demonstrators. This was England, reflecting its queen’s example, even as she broke royal protocol by bowing her head at the passing cortege — a telling reminder, once again, that Elizabeth understood the power of small things and how hugely they were marked and appreciated.

The virtue of stability

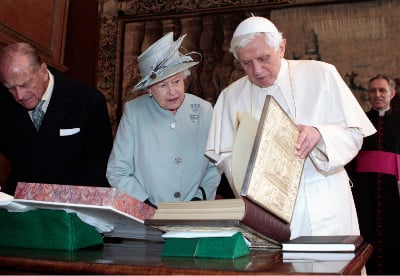

As I write this, the queen’s body is stationed at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, Scotland, before heading to London. It was at Holyrood, nearly 12 years ago to the day, that the queen (who met five popes, from Pius XII to Francis during her reign) greeted Pope Benedict XVI on his historic visit to England. At this meet-up between generational contemporaries, Elizabeth spoke not only as sovereign but as supreme governor of the Church of England. She again used unremarkable words to signal that these two octogenarians — the last world leaders to have lived through the jackboots and totalitarian horrors of the recent past — had a shared and important message: that faith freely lived is the nonnegotiable foundation of every other freedom.

“We know from experience that through committed dialogue, old suspicions can be transcended and a greater mutual trust established. … Your Holiness, in recent times you have said that ‘religions can never become vehicles of hatred,’ that ‘never by invoking the name of God can evil and violence be justified.’ Today, in this country, we stand united in that conviction. We hold that freedom to worship is at the core of our tolerant and democratic society.”

Elizabeth’s unfussy words once again defined England as something steadfast, faithful and optimistic, while reminding us that, even as things change, as change must come, adhering to the fundamentals is what guarantees stability. And stability, she demonstrated again and again, is a virtue upon which lasting futures might be quietly, powerfully built.

Elizabeth Scalia writes from New York.