When Christians think of participation in the resurrection of Christ, our default image is of sharing eternal life with God. Christ rose from the dead and ascended into Heaven, making it possible for us to do the same. The hope of eternal life and heavenly glory is, in fact, the essence of Easter faith. Our own resurrection after death, sharing in Christ’s, is deliverance into a realm that we consider to be outside of time and space, at least as we understand those terms. Thus, the effect of Christ’s resurrection is a current promise for a future reward, but then for all eternity. Everlasting rest and joy in the presence of God is our ultimate end.

All of this is right and just. But we Christians also understand both that the Resurrection has meaning for our lives in the here and now, and that our future hope is not a promise of escape from current suffering. On the contrary, the hope of resurrection is more a means of situating suffering than it is a promise that suffering will be taken away from us. As much as a promise of future relief, resurrection is a paradigm for understanding contemporary sorrow.

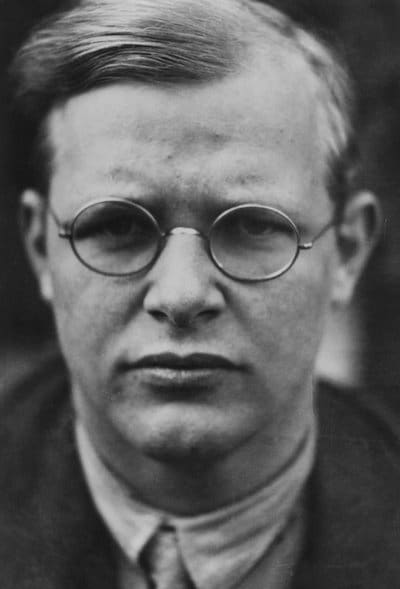

The great Christian martyr and Lutheran theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer distilled this understanding of resurrection in one of his many letters from prison. Bonhoeffer had been imprisoned in April 1943 by the Nazi regime for his alleged participation in a plot to assassinate Hitler. He was hanged in April 1945, at the age of 39, on the eve of Allied victory in Europe and mere weeks before the liberation of the prison camp in which he had been consigned. While in prison, Bonhoeffer wrote hundreds of letters, many of which were smuggled out by sympathetic guards, and later collected in the volume, “Letters and Papers from Prison.”

Historical versus mythic redemption

One letter, from June 1944, challenges us to understand that the Resurrection does not merely promise life after death. Rather, Bonhoeffer contends, the Resurrection redeems suffering in the present, earthly lives of Christians. In doing so, he sought to interpret the death and resurrection of Jesus through the theology of redemption in the Old Testament. Failure to see Christ’s redemptive work through this interpretive lens causes us to have a truncated understanding of Christ’s work.

To the extent that the Old Testament has a theology of redemption, contends Bonhoeffer, it is “redemption within history, that is this side of the bounds of death.” He explains that this contrasts with contemporary rival redemption myths, which sought to escape time and space.

“[T]he aim of all other myths of redemption is precisely to overcome death’s boundary,” he explains. “The redemption myths look for eternity outside of history beyond death.” In contrast, “Israel is redeemed out of Egypt so that it may live before God, as God’s people on earth.” Israel’s redemption is effected in time and space.

We must not separate the work of Christ from the history in which his resurrection occurred. The Resurrection happened in time and space to redeem them both.

Bonhoeffer is onto something. Ancient Israel (and thus the Old Testament) does not have a systematic theology of life after death. Later allusions to an afterlife are implicit, embedded in narratives such as the story of the Maccabees. But one looks in vain for a theology of the afterlife.

Israel’s understanding of redemption in time and space should be an interpretive tool for developing a fuller understanding of Christ’s resurrection. Without denying the hope of eternal life, Bonhoeffer cautioned that we must read the resurrection of Christ through this Old Testament precedent of God’s redemptive work. We must not separate the work of Christ from the history in which his resurrection occurred. The Resurrection happened in time and space to redeem them both.

Drinking the ‘cup of earthly life’

This reorientation of our understanding of redemption has important implications for our moral and spiritual lives, Bonhoeffer continues. Redemption must not be reduced to “being redeemed out of sorrows, hardships … and longings.” It is not an “escape route out of … earthly tasks and difficulties.” Rather, Christians “have to drink the cup of earthly life to the last drop.” Only then “is the Crucified and Risen One with them, and they are crucified and resurrected with Christ.”

Of course, Bonhoeffer’s reading of the Resurrection is shaped by his experience of imprisonment. But rather than to dull his sense of redemption, it is honed by this ordeal. Christ did not redeem him merely so that he could have life in heaven. Rather, the redemptive work of Christ gave context and purpose to his suffering on earth. The suffering is not removed; it is redeemed. But this must be an intentional move of faith. We must reorient our understanding of the Resurrection to encompass both eternal life beyond and redemption of suffering here.

“Redemption myths arise from the human experience of boundaries,” explains Bonhoeffer. “But Christ takes hold of human beings in the midst of their lives.” This is a bold and challenging Easter message. Christ did not die to take us out of this world, but to affirm our existence in it. Yes, we have the hope of resurrection in the future. But we have the faith of redemption in the here and now.