There is an ancient Christian saying, which remains a prominent feature of Catholic life and a Catholic outlook: Tempus fugit, memento mori (“Time is fleeting: remember death”). We are called to remember our death and look after our eternal souls. Scripture reminds us of this again and again: “By the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread, Until you return to the ground, from which you were taken; For you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Gn 3:19); “My son, shed tears for one who is dead, with wailing and bitter lament; As is only proper, prepare the body, and do not absent yourself from the burial” (Sir 38:16).

There is also a profound hope because of Christ’s salvific death and resurrection. “Or are you unaware that we who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death, so that just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might live in newness of life” (Rom 6:3-4); “We do not want you to be unaware, brothers, about those who have fallen asleep, so that you may not grieve like the rest, who have no hope. For if we believe that Jesus died and rose, so too will God, through Jesus, bring with him those who have fallen asleep” (1 Thes 4:13-14).

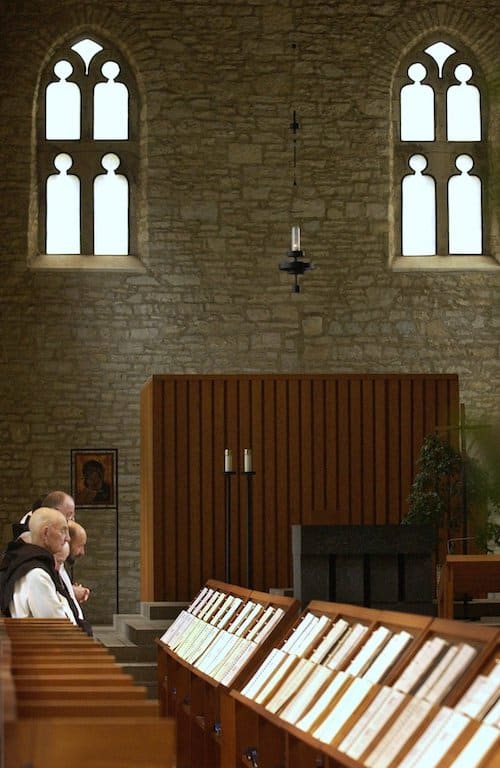

The monks at New Melleray Abbey in Peosta, Iowa, maintain an apostolate building caskets and urns, playing their part in encouraging respectful and dignified burials, and keeping death before our eyes. This is a participation in the corporal works of mercy.

The monks at New Melleray are Trappists — members of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO). Originally, the order was known as the Order of Reformed Cistercians of Our Lady of La Trappe, hence the name “Trappists.”

The Trappists were formed in 1664 at La Trappe Abbey in France (although the wider Cistercian family traces its origins back to 1098), and the monks who founded New Melleray Abbey came to Iowa in 1849, after a grueling 77-day journey from Ireland. Trappists follow the monastic Rule of St. Benedict, written around 1,500 years ago, which organizes and guides their way of life. One of the most important principles in this Rule is ora et labora — prayer and work. The day is split between these two essentials, although most monks would tell you that even your work should be prayerful.

Honoring body and soul

At New Melleray Abbey, their casket- and urn-building business is prayerful work that helps lend sanctity to the grieving process. The work is done by monks of the Abbey and hired laypeople, and every casket and urn is blessed by one of the monks. It is not just about providing a container for mortal remains. Each casket comes with a keepsake cross, engraved with the deceased’s name and dates, which is given to the family; a memorial Mass is said at the Abbey for the deceased; and the deceased’s name is inscribed in a memorial book, which is kept in the Abbey chapel. The monks send handwritten condolences at the time of loss and on the first anniversary of the individual’s death. And for each person buried in a Trappist casket or urn, the monks at New Melleray plant a new tree in their sustainable forest as an ongoing, living memorial.

Many religious orders support themselves by providing services that people need. They farm and sell their produce; they brew beer and sell that; they run schools or media apostolates. But why is a casket something we need? Why do we treat the dead with such respect?

First and foremost, we know that our bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit. “Do you not know that your body is a temple of the holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God, and that you are not your own? For you have been purchased at a price. Therefore, glorify God in your body” (1 Cor 6:19-20). Here, St. Paul tells us that our bodies are important, and must be treated with respect. Even after we die, we must continue to treat our bodies with dignity.

There is a fairly common heresy today, which is sort of a species of Gnosticism, that says that we are purely spiritual beings in a temporary physical state. In reality, the human person is comprised of a unity of body and soul: “The unity of soul and body is so profound that one has to consider the soul to be the ‘form’ of the body: i.e., it is because of its spiritual soul that the body made of matter becomes a living, human body; spirit and matter, in man, are not two natures united, but rather their union forms a single nature” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, No. 365). If the body was merely a shell that was to be discarded at death, there would be no point in respectful and dignified burial rituals; in such a case, the body would simply be organic matter to be discarded. But this is not the case.

The Catechism continues further on: “The bodies of the dead must be treated with respect and charity, in faith and hope of the Resurrection. The burial of the dead is a corporal work of mercy; it honors the children of God, who are temples of the Holy Spirit” (No. 2300).

Corporal work of mercy

So what does it mean to say that burying the dead is a corporal work of mercy? The “works of mercy” come to us from the mouth of Jesus, in his somewhat terrifying warning in Matthew’s gospel: “For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me” (Mt 25:35-36). These are known as the corporal works of mercy, as they have to do with the body, as opposed to the spiritual works of mercy. Traditionally, the final corporal work of mercy identified is burying the dead.

Jesus tells us that failure to perform these works of mercy results in damnation. He will say to those, “Depart from me, you accursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” (Mt 25:41).

The work of the monks at New Melleray fulfills our calling to treat bodies with respect, and provide a dignified burial. It is a testimony to our belief in the resurrection of the body and life everlasting, and in the dignity of the human person.