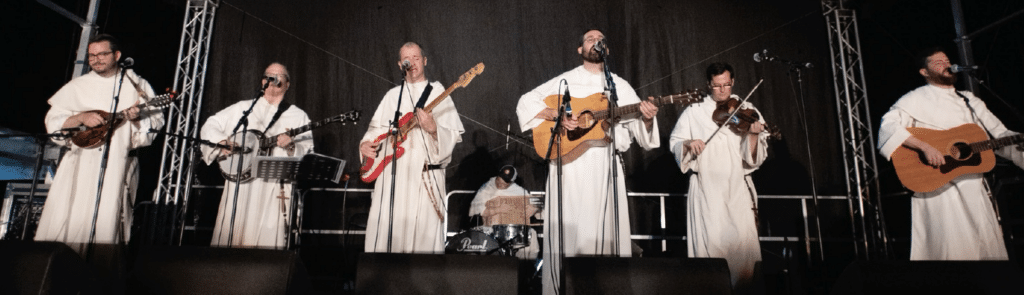

The hall darkens. The crowd falls silent. Lights from above the timber-framed stage illuminate a banjo, piano, drum set, mandolin and an assortment of guitars and microphones. To a chorus of cheers, seven men, dressed in white robes that look like they’d fit better into a medieval mystery play than a modern concert hall, stride onto the stage.

One of them strikes up a melody on a mountain dulcimer, the line accompanied only by the low drone of the remaining strings. A second musician begins to strum a guitar and sing, and soon the rest of the band launches into a joyous, harmonious performance.

The musicians are Dominican priests, and their white habits have indeed changed little since the 13th century. But tonight, the friars are not here to preach, say Mass or hear confessions. They are the members of The Hillbilly Thomists, and they take the stage of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee — one of the most revered performance halls in American entertainment — to play their unique brand of bluegrass and old-time music.

A mischievous take on an American tradition

Now we’re living off of Johnny Cash,

— “Old Highway” by The Hillbilly Thomists

cold coffee, and grace.

Don’t got to pass no more tests,

don’t got to save no more face. …

‘Cause we keep on wandering, like

pilgrims on the way

To the land of heaven in a Chevrolet.

The Hillbilly Thomists have been playing music in some form since 2008, when Father Thomas Joseph White and Father Austin Litke recognized a shared interest in bluegrass music while at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. In homage to St. Thomas Aquinas — the best-known Dominican friar after St. Dominic himself — and the novelist Flannery O’Connor, a fellow Georgian to Father Thomas Joseph, the two took the name “The Hillbilly Thomists.” O’Connor, who read from St. Thomas’ Summa Theologiae each night, once wrote, “Everybody who’s read Wise Blood thinks I’m a hillbilly nihilist, whereas I would like to create the impression … that I’m a hillbilly Thomist.”

The two friars started “giving little talks and then just making people listen to music,” Father Austin tells me. “That’s the real beginning of the band: a captive audience. And then it turned out that people actually liked it.”

After years of the two priests playing music together, a group of Dominican student brothers at the House of Studies joined them in 2015, and the band was born. Several of these young friars had professional musical training and experience: Father Peter Gautsch graduated with a degree in piano performance from the University of Notre Dame, playing jazz and classical music; Father Justin Bolger had a record deal and multiple Americana recordings playing with his sister as Judd and Maggie, and Father Simon Teller had been a member of the Stillwater Hobos, whose Irish/folk album “My Love, She’s in America” remains treasured by fans. Along with these three, Father Jonah Teller (the biological brother of Father Simon), Father Joseph Hagan and Father Timothy Danaher also joined the band.

Father Thomas Joseph admits there is a “layer of mischievousness” to a band of Catholic priests, wearing habits that originated in 13th-century Europe, singing songs of American Protestantism. “Of course, when a priest says, ‘What would you give in exchange for your soul,’ it means something a little bit different, or has a Catholic inflection all of a sudden. But at the same time, it’s an appreciation of something in the American tradition,” he says. Over the course of four albums, the band has remained rooted in that American spiritual tradition, even as they’ve branched out musically and lyrically in their own songwriting and arrangements.

From fraternal recreation to ‘this is a thing’

I’m a dog with a torch in my mouth for

— “I’m a Dog” by The Hillybilly Thomists

my Lord,

Making noise while I got time,

Spreading fire while I got earth,

How You wish it was already lit.

Give me Your fire, I’ll do Your work.

I’m just a dog for my Lord.

At first they played “just by delight,” Father Thomas Joseph tells me, as a form of community and fraternity. But as others caught on and began requesting performances for events, the friars realized their music could be more than fraternal recreation.

The Dominican friars at the House of Studies had already recorded four albums of sacred music. Father Justin, with his experience in songwriting and recording, suggested that the band record an album of traditional American music. This led to the release of “The Hillbilly Thomists” in 2017.

To the friars’ great surprise, “The Hillbilly Thomists” reached #3 on the Billboard bluegrass chart and gained the attention of a nationwide audience. “The first album did better than any of us could have imagined,” Father Austin says. “And so we thought, ‘Oh, this is a thing.'”

That first record consisted mostly of new arrangements of traditional American spiritual, gospel and bluegrass songs: “Amazing Grace” in 4/4 time, “What Wondrous Love is This” with extended solo trading between fiddle and mandolin, a version of “Poor Wayfaring Stranger” that remains the band’s most-streamed song online. It contained one original song written by Father Justin: “I’m a Dog” alludes to the Dominicans’ moniker, “hounds of the Lord.”

The success of the first record was followed by a period of quiet from the Thomists. The men who had joined the band as student brothers in the House of Studies were ordained priests and assigned roles throughout the Province of St. Joseph, the order’s eastern U.S. province. Four years passed before the release of 2021’s “Living for the Other Side.”

When I ask the band what drove the return to the recording studio and the shift to primarily original songs in the new album, Father Thomas Joseph answers with one word: “COVID.” It was the lockdowns that afforded them time to write and play music and, after years apart due to priestly assignments, put together an album of new songs.

Since then, the band has performed two summer tours, including the stop at the Grand Ole Opry in 2022, and recorded two more albums: 2022’s “Holy Ghost Power” and 2024’s “Marigold.” The one thing that has remained constant across these albums is their musical variety.

I tell the band that I think of their genre as “eclectic Americana” because they pursue so many different musical styles. Father Jonah jokes — I think — about this being a slander, but I explain that I mean it as a compliment.

Father Thomas Joseph suggests that AC/DC and Lynyrd Skynyrd built their whole careers around all their songs sounding the same, and that “Lynyrd Skynyrd is an institution.” The priests banter for a few minutes in this apparently long-standing though lighthearted dispute about the degree of originality that must go into each song.

The variety comes from many sources. For one, there are multiple songwriters in the band. Father Thomas Joseph and Father Justin write the majority of original songs for the group, but Father Jonah, Father Peter, Father Timothy and Father Austin all have songwriting credits as well. Then, when a priest brings a song he has written to the group, other members may have their own ideas to contribute to the arrangement and style of the tune. Finally, stylistic variation is an intentional goal of some members of the group. Father Justin tells me that he’d get “bored as hell” if they played the same thing over and over in each song, and Father Peter points out that exploration of new styles and sounds is a deliberate choice.

The discussion brings up what seems to be a real disagreement, but it does not carry with it any of the hard feelings or frustration that might come with such disagreements in a band more oriented toward commercial success. In this exchange, I see the friars living out their brotherhood in good-natured teasing, in knowing and loving each other well.

This fraternity is at the heart of the band, how it started and what sustains it. When I ask about the relation of music and preaching, Father Peter emphasizes that the music does serve as a function of their lives as preachers, but first, it grows out of community, and that making music together continues to be a joy for the friars.

A soundtrack of consolation

Death’s in the world and it’s gone viral.

— “Bourbon, Bluegrass, and the Bible” by the Hillbilly Thomists

Everybody’s talkin’ ’bout a new revival.

When it’s a question of love and survival:

Bourbon, bluegrass, and the Bible.

Part of what makes The Hillbilly Thomists unique as a musical act is that they are only able to be full-time musicians, recording or touring, for a couple of weeks each summer. The priests are scattered across the world for most of the year. Father Thomas Joseph, for example, is the first American rector of the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas — known as the Angelicum — in Rome and has been granted the title of “Master of Sacred Theology” by the Dominican Order for his work in the field. Other band members serve across the U.S. in parishes in New York City and St. Paul, Minnesota, or as chaplains at Providence College, Dartmouth College, Brown University and The Catholic University of America.

Even as the band’s notoriety grows, the members remain priests first. Rather than seeking fame, they use their music as a way to cooperate with God’s grace and the work he wants to accomplish through them.

The friars have been surprised at the ways God has used their music: Their songs have served as a soundtrack of consolation for many listeners. “In the spiritual life, you don’t often see the fruit of your labors, whether it’s priestly ministry or family life,” Father Peter says. “However, people do write us to say, in ways that are really unexpected to us, that our music has really meant something to them or has helped them through a difficult time.”

“You meet (people) on tour, and they’re crying telling you what this song meant. It changes your whole approach to what you’re doing,” says Father Thomas Joseph. “This is actually something beyond us … something God has done.”

Families have written to the priests to tell them that the title track from “Marigold,” written by Father Justin, has been a source of consolation when they’ve experienced miscarriage. The third verse is particularly striking:

When the wheat bled out, blood on the spikes,

I sang a Maris Stella like my father.

And what I first intend, I will finally hold.

In time a bloom will come, my marigold.

The verse is based on a story from the life of St. Dominic, and Father Justin points out that he had in mind the Eucharistic imagery of the miracle. But, as Father Thomas Joseph points out, songs are able to take on new meaning for different listeners, and God uses the music in ways the band members never imagined. But some listeners who have experienced miscarriage have also found comfort in the song.

Parents aren’t the only ones moved by the Thomists’ music. “We’ve single-handedly and without any intention or effort on our part created one of the largest children’s ministries in the history of our province,” Father Thomas Joseph says with characteristic irony. He describes groups of 4-year-olds singing along to “Bourbon, Bluegrass, and the Bible” and shouting out lyrics about “suffering under the weight of eternal glory” at the band’s live shows.

I’m listening to “Living for the Other Side” as I write, and, indeed, when “Bourbon, Bluegrass, and the Bible” comes on, my 7-year-old, without any prompting, tells me with a grin that it’s his favorite song. The band’s website even hawks onesies that read, “Bottles, Bluegrass, and the Bible.”

But their most popular original song has much more going for it than its appeal to younger listeners. As with many of Father Thomas Joseph’s songs, it strikes a balance between the sacred and the ordinary, the traditional and the modern, the eccentric and the profound. Father Thomas Joseph is as comfortable “talkin’ ’bout grace and talkin’ ’bout sin” as he is writing that “death’s in the world and it’s gone viral.” Or, in “Holy Ghost Power,” singing about “a hundred channels of nothing on the TV at ten / It’s like Diet Coke and original sin.” The theologian digs into these paradoxes in his songwriting, drawing out the pilgrim status and dual, body-soul nature of mankind. “We’re a little bit of angel, we’re a little bit of dust,” the Thomists sing in “Satisfied Man.” “We’re a little bit of cold hard fact, we’re a little bit of trust.”

In this, the band writes from the American musical tradition and brings it forward into the modern age. As part of that tradition, though, the music documents the human condition, the ambiguities of life on earth, without giving in to a saccharine faith or false vision of reality. In their songs, the friars pick up the dictum of Flannery O’Connor for artists, “squarely facing reality in the light of grace,” Father Peter says.

Divine simplicity

I am looking forward to that day you

— “Sing Redeeming Love” by The Hillbilly Thomists

call, I joyfully obey

When I will see my Savior, hear the

choirs above, sing redeeming love.

As a musician who reads Aquinas now and then and has read most of Flannery O’Connor’s fiction, essays and letters with great delight, I thought of myself as the Thomists’ ideal demographic. But as I talk with the band members and dig deeper into their recordings and history, it’s clear that their music is not just for a niche audience. The secular Country Music News International recognized this, writing that the band has “gained popularity for their spirited performances and their ability to connect with audiences through both their faith and their music.”

Music has the ability to strike the human heart in ways we can’t fully understand or explain. Sometimes, this can be through depth and complexity — lyrics with layered and metaphorical meaning, intricate melodies, complex harmonic structures and chord movement. Such songs provide a richness that we can return to again and again, plumbing deeper each time. Often, though, the songs that strike us most powerfully and emotively are incredibly simple — “three chords and the truth,” as Harlan Howard famously described country music. The Hillbilly Thomists are comfortable at both ends of this spectrum.

Father Peter and I talk about how the nature of music is itself a reflection of God: infinitely simple yet infinitely intelligible, with a depth of reality that in all of eternity we can never fully plumb.

My favorite Hillbilly Thomists song, “Sing Redeeming Love,” is written by Father Justin but sounds like it could be an old Stanley Brothers tune. With a simple pentatonic melody over just three chords, the band sings, “I am looking forward to that day you call / When I will see my Savior, hear the choirs above, sing redeeming love.” At the end of the song, the friars all sing together, their voices set back from the microphone and blending into one communal chorus, “Gimme that old time religion, gimme that old time religion / Gimme that old time religion, it’s good enough for me.” This song is the perfect example of the powerful simplicity of music, voices joining and blending together in a unity directed toward fulfillment in God and the heavenly host.

Music itself, Father Peter says, is a sign and reflection of God’s goodness. “That he made a world with music in it is already gratuitous. If different levels of complexity of the music can reflect even that, then we’re very happy about that.” Indeed, the band captures some reflection of this in their far-reaching style, from the richness of “Marigold” to the simplicity of “Sing Redeeming Love.”

The grace of music

There’s a line from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” that I’ve carried with me for years but have never fully understood: “For the glory of God is the living man, and the life of man is the vision of God.” Brought up in a society imbued with individualism and the Protestant work ethic, I’ve most often thought “all glory to God” was about praising God through our efforts and accomplishments. But talking to Father Peter about the band, this quotation came into focus in a new way. The friars do teach and preach through their music, they do evangelize and build up the kingdom of God, but they do these things incidentally, through God’s gratuitous grace. Primarily, they glorify God simply through the delight of their music, through living their vocations and lives fully, boldly, joyfully, using their talents and the opportunities God has provided, whether that be on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry or in their own priory.

If we live out our vocations faithfully and live close to Jesus, joy and grace will fill us and pour out. The Thomists don’t have to contrive to sing songs about conversion, about “Johnny Cash, cold coffee, and grace,” or about “living for the other side,” because they joyfully live that life, and the music overflows from that well. Father Justin writes in one song, “Won’t you put in me a well I can draw from all my life,” knowing that God wants to respond with a powerful yes. Christ gives us the well of the sacraments, of his own body and blood, but also the grace of music, community and the delights of good things on earth and the promise of heaven.

The Hillbilly Thomists plan to record another album in the summer of 2025. You can buy CDs and merch and reach out to the band at their website, hillbillythomists.com. All sales support the work of the band, as well as the formation of friars at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C.