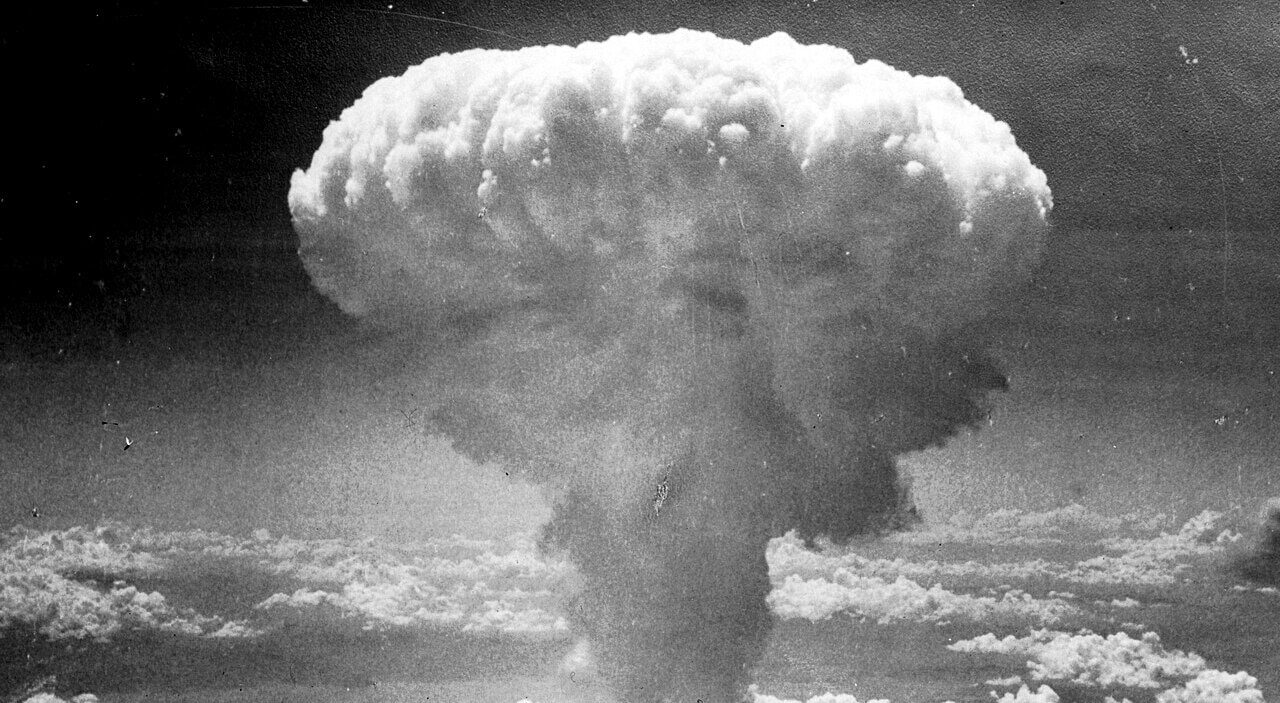

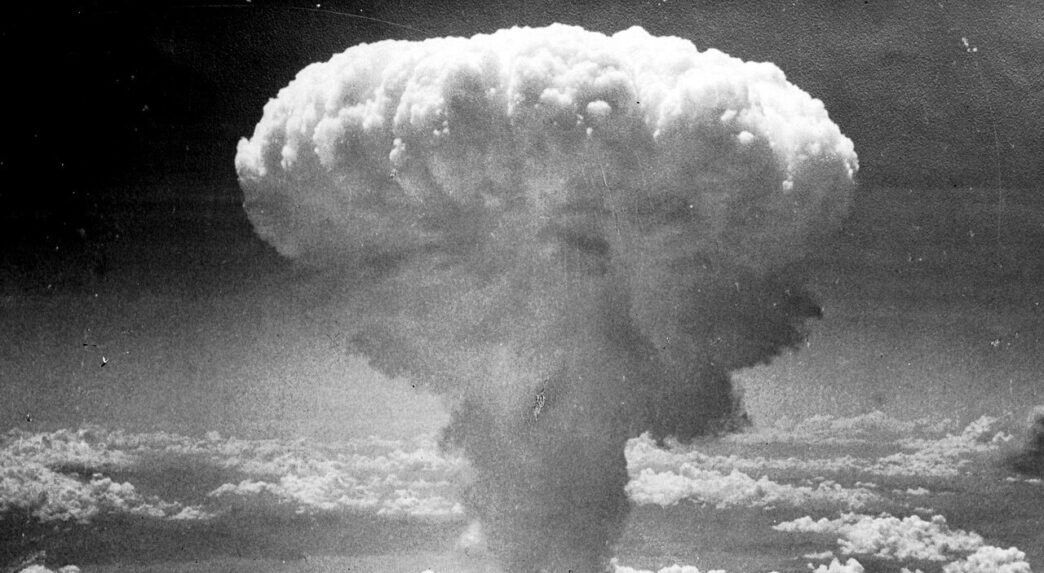

On Aug. 15, 1945, in Japan (Aug. 14 in the U.S.), Japan announced its intention to surrender unconditionally to the Allies, ending World War II in the Pacific theater. (The war in Europe had officially ended the previous May 8.) Known alternatively as “Victory in Japan Day” or “Victory in the Pacific Day,” the end of hostilities is commemorated on Aug. 15 in Europe and Sept. 2 in the U.S., the latter being the day the formal surrender document was signed aboard the American battleship, U.S.S. Missouri. Of course, Japan’s unconditional surrender was preceded by the bombing of the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki ( Aug. 6 and 9, respectively) and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan on Aug 9. The 80th anniversary of V-J Day is, once again, the occasion to consider the morality of dropping the two atomic bombs on Japan.

The standard defense of the use of nuclear bombs in Japan is straightforward. Defenders assert that Japan would never surrender without a massive ground invasion by the allies. Such an invasion, the theory asserts, would come at the cost of extremely high casualties, both American and Japanese. Thus, the contention goes, the use of nuclear weapons saved both American and Japanese lives. For example, writing in First Things, George Weigel asserted that dropping the bombs “saved millions, even tens of millions, of lives, American and Japanese” (his emphasis). In a remarkable concession, Weigel actually admits that it is “difficult, if not impossible, to vindicate” the bombings “without relativizing moral norms” articulated in St. John Paul II’s encyclical Veritatis Splendor (“The Splendor of Truth”). Even so, Weigel draws the puzzling conclusion that dropping the bombs was “the correct choice.”

For a Catholic, this kind of reasoning is mistaken for at least three reasons. First, it uses illicit utilitarian moral analysis. Second, it expressly justifies intending evil means for an allegedly good end. Third, it ignores contemporary evidence that Japan was on the verge of surrendering before the bombs were dropped. (It is not my intention to condemn Weigel, who is a faithful Catholic and long-time friend. But his article is a ready example of a common argument in defense of dropping the bombs on Japan. I believe he is gravely mistaken, of course. But I criticize the argument, not the man.)

The utilitarian argument

Defenses of the bombings like Weigel’s build their entire argument on a straightforward utilitarian moral analysis. Killing X number of a certain population is “the correct choice” because it (allegedly) saves the lives of a different population of X + 1 number of people. From the Catholic point of view, this is a category error. It is built upon the illicit premise that one can use person A as nothing more than a means to achieve a favorable outcome for person B. One may kill person A to save the life of some hypothetical person B. Person A, therefore, is nothing more than the actual means to some speculative end.

This reasoning cuts against the entire history of Catholic moral reasoning. Made in the image and likeness of God, human beings may never be used merely as the means to some end. Weigel admits as much in his invocation of “The Splendor of Truth,” but concludes that the bombings were “the correct choice,” nonetheless. But both these things cannot be true. If utilitarianism is false, it cannot be used to justify any moral action. Essentially, Weigel’s argument takes the incoherent position that the bombings were morally wrong but morally justified. This is, of course, a flat contradiction.

‘The end justifies the means’ argument

Arguments like Weigel’s similarly violate the bedrock moral principle that one cannot use evil means to justify an alleged good result. Even if the end of the war is a moral good, Weigel’s concession that it was achieved by an immoral action violates this principle. “And why not say … that we should do evil that good may come of it?” as some people argue, according to St. Paul the Apostle. “Their penalty is what they deserve,” he responds (Rom 3:8). From this, we derive the principle that “One may not do evil so that good may result from it,” as stated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (No. 1761).

Catholic moral reasoning focuses less on consequences of actions than on the status and development of the human moral agent. To claim that a good end can be justified by evil choices necessarily implies that it is sometimes good for a person to will evil. Of course, this is another contradiction. Willing an evil action is evil even if, for the sake of argument, the intended evil action produces some alleged good. Weigel concedes that his argument utilizes “the kind of ethical calculus” rejected by John Paul II in “The Splendor of Truth.” It is also rejected by the Catechism: “There are concrete acts that it is always wrong to choose, because their choice entails a disorder of the will, i.e., a moral evil” (CCC, No. 1761).

The dubious historical argument

Finally, nearly all justifications for dropping the nuclear bombs on Japan, including Weigel’s, depend on dubious historical arguments about the state of Japan’s war aims in the summer of 1945. It is certainly true that one camp in Japan’s political and military leadership advocated a burn-down-the-house defense of the island. This element advocated that Japan should never surrender, even to the last person standing. But the historical record also shows strong objection to this approach among some Japanese military and political leadership.

Because the United States had largely broken Japanese military codes, U.S. intelligence knew that an opening for a negotiated surrender existed in August 1945. For example, General Douglas MacArthur said there was “no military justification for the dropping of the bomb.” Similarly, General (later President) Dwight Eisenhower said in his memoir “Mandate for Change, 1953-1956: The White House Years,” “It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.'” In a 1963 “Newsweek” interview, Eisenhower added, “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.” Similar contemporary opinions were voiced by Admiral William Leahy, and General Carter Clarke, among many others.

Clarke’s insight is especially noteworthy, because he was the intelligence officer who prepared memoranda from intercepted Japanese communications. “We didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew we didn’t need to do it,” Clarke was quoted as saying after the war. Clarke was one of a number of people who thought Truman’s motivation in dropping the bombs had less to do with ending the war with Japan, and more to do with making a show to the Soviet Union. Truman, this theory goes, did not want the Soviet Union to join the war in the Pacific, because he feared Soviet claims of hegemony if they built a stronghold in the South Pacific. Moreover, the same contention goes, Truman wanted to use the bombs as a show of force against the Soviets. These are highly debated historical theories, of course. Even apart from the moral considerations, historians are divided on the status of Japan’s internal discussions about surrender. But the argument itself is an answer to the smug conclusion that Japan’s surrender prior to Aug. 6 and 9 was not a known possibility.

From the standpoint of Catholic moral theology, the arguments typically used to justify the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are simply not available. They are moral theories that are categorically rejected by the Church. George Weigel’s “First Things” article is entitled “Truman’s Terrible Choice, 75 Years Ago.” Five years of consideration later, it was still a terrible choice. It was not just terrible, though. It was immoral.