In the predawn hours of June 6, 1944, Conventual Franciscan Father Ignatius Maternowski parachuted behind German lines near Guetteville, France, a small village in Normandy, with the men of the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division.

His company’s mission was to secure bridges to make the Allied invasion of Normandy faster and easier, but it was no simple task, especially after the paratroopers were scattered in the drop zone and came under fire.

By nightfall, Father Maternowski was dead, believed to be the only U.S. military chaplain killed in the invasion on D-Day. His story is one the Our Lady of the Angels Province of the Conventual Franciscans plan to share widely. Perhaps, said Conventual Franciscan Father Martin Kobos, he could one day be a saint.

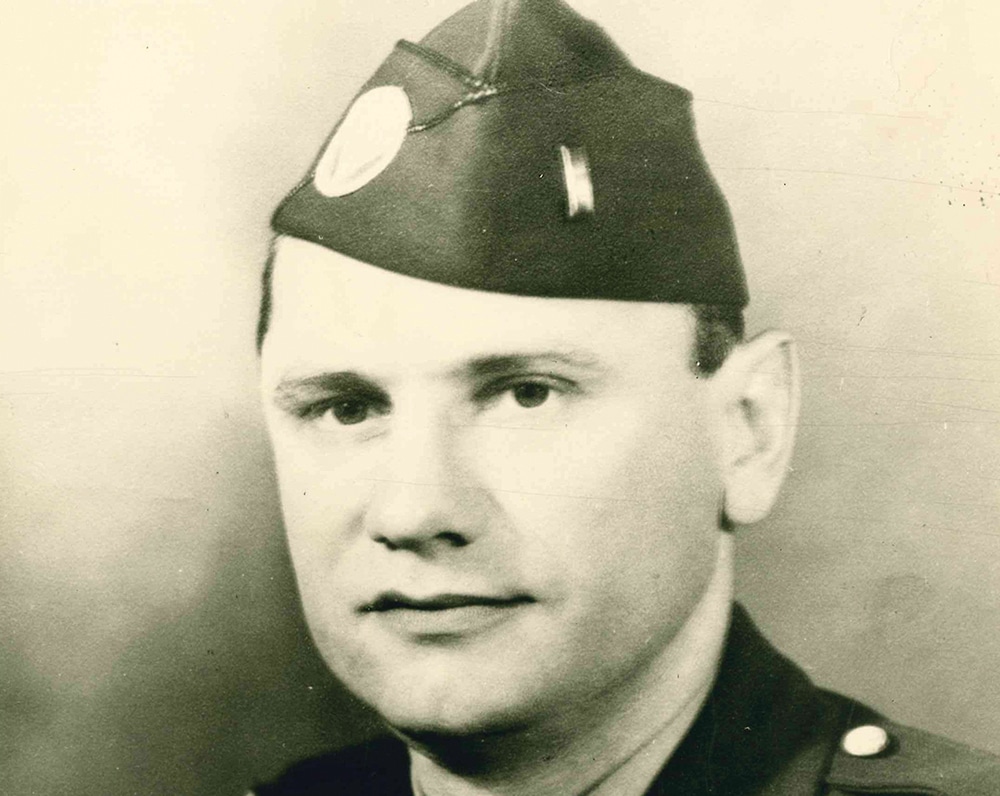

Father Maternowski was 32 years old when he died, a Conventual Franciscan for over a decade and a priest for five years. He had volunteered as a military chaplain with the permission of his superiors in 1942, and D-Day was his first time in combat.

While the basics of his story have long been known among his brother friars — Father Kobos first saw Father Maternowski’s name on the “Athlete of the Year” plaque, dedicated to the former Army chaplain, at St. Francis High School, near Hamburg, New York — more details are coming out, and Father Maternowski has drawn new attention.

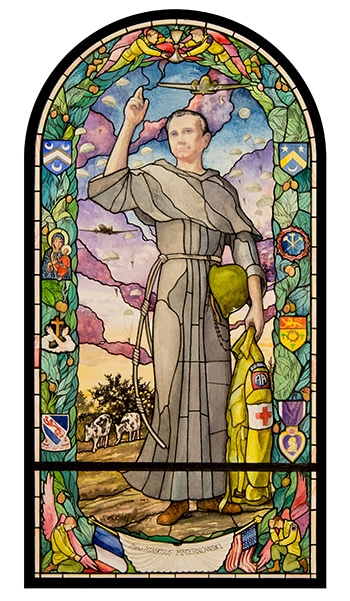

Conventual Franciscans and members of the military traveled to Guetteville last June to visit a memorial to Father Maternowski on the 75th anniversary of D-Day, and now his Conventual Franciscan Province has commissioned a stained-glass window depicting Father Maternowski that will be installed in the 800-year-old village church next June.

A moment of heroism

Even so, Lt. Col. Brian Koyn, division chaplain for the 82nd Airborne, had never heard of Father Maternowski until he was invited to the June 2019 memorial, he said. Koyn is in his second assignment with the 82nd, having previously served there as a battalion chaplain from 2006 to 2008.

The reason for his obscurity?

“It might be that his story is so short,” Koyn said. “His combat experience lasted all of about 12 hours.”

Other chaplains ministered to soldiers in combat situations for years and lived to tell the tale, Koyn said.

It might also be that Father Maternowski’s example is not necessarily one the Army would encourage its chaplains to follow.

“What he did, it sounds like it might be a little bit naive,” Koyn said. “But really, he was in an ethical dilemma. When you have a dilemma, you’re faced with a bunch of crummy options. And I think that’s something all our chaplains can learn from.”

The dilemma was this: Wounded American paratroopers were being treated, as much as possible, in an unmarked building in an area occupied by the Germans. American troops also were storing ammunition there.

In the confusion of the fighting, Father Maternowski — a captain, and, as chaplain, an unarmed noncombatant — found himself the ranking officer on the scene. The wounded needed more help than he or the medics could provide, and with no identification of the building as a medical aid station, it was in danger of being attacked.

So Father Maternowski took off his helmet and carried a white flag as he approached the German line, about a hundred yards away. He got the attention of the German medical officer, and proposed that they create a combined aid station for the wounded from both sides. He escorted the medical officer back to the makeshift American aid station to demonstrate its inadequacy. Then he walked back toward the German lines with the man. It was when he turned to return to the aid station that a sniper shot him in the back.

“He probably had training in the Geneva Convention — or at that point the Hague Convention — that said chaplains and medics were not to be targeted, and neither were the wounded,” Koyn said. What he didn’t have was the combat experience to know that those rules were not always honored.

Still, given the situation of the wounded — trapped in a building with ammunition, a football field’s length away from the German lines — they likely would have been overrun and killed had Father Maternowski done nothing, Koyn said. Given that, his decision to do something — to appeal to the humanity of the Germans in the hope of helping everyone involved — makes more sense.

“He acted in good faith, and he wanted the best for his paratroopers,” Koyn said.

Maternowski’s humanity

Father Maternowski’s story started in the town of Holyoke in western Massachusetts. The Conventual Franciscans ministered to the Polish community at Mater Dolorosa Parish, which has since been closed.

He was in the first class to graduate from the Conventual Franciscans’ St. Francis High School in Hamburg, which took both boarding and day students, and then entered the order. When World War II started, he was one of many Conventual Franciscans who volunteered as chaplains, Father Kobos said.

“The understanding was that the soldiers were going to need their priests,” Father Kobos said. “And the Franciscan charism is to bring peace to a troubled world. Even in the midst of war.”

Father Maternowski’s devotion to his men comes through in a passage of the book “Serving God and Country: U.S. Military Chaplains in World War II” by Lyle W. Dorsett (Berkley Books, $25.95). While the book makes no mention of Father Maternowski’s death, it speaks of how well the “tough, energetic little Pole” related to his men, and how he was quick to defend his faith — especially against those who disparaged the Sacrament of Confession — with his fists.

John Dabrowski, a retired Army colonel and a retired history professor, put it more succinctly: “You’re probably looking at a guy with more guts than brains,” he said.

At the same time, Dabrowski said, Father Maternowski’s character shines through in the accounts of what he did.

“Trying to set up an aid station, and then to put himself in harm’s way, to do what he did … to do something like that really showed the humanity of the man,” Dabrowski said.

Dabrowski was able to confirm many of the details of Father Maternowski’s story when he was asked to look into it by Father Robert Berger, who was Dabrowski’s mother’s former pastor at a Pennsylvania parish. Father Berger, a priest of the Diocese of Harrisburg, is the founder of the WWII Chaplains Memorial Foundation.

The research called on Dabrowski’s academic skills as well as his knowledge of military record-keeping and military contacts, Dabrowski said.

“Maternowski was not a known entity,” he said, adding that many of the facts as they had been reported were in question, including whether Father Maternowski died on D-Day or a couple of days later.

Once he turned the information he found over to the Conventual Franciscans, he thought he was finished with the project. Then he was invited to speak at the ceremony in Guetteville in June.

Dabrowski said he is continuing to look into the story and has hopes of finding out who the medical officer that Father Maternowski conferred with was.

He also hopes Father Maternowski is one day recognized as a saint.

“I would love to see it come to fruition,” he said.

For that to happen, more people need to be aware of Father Maternowski’s life and sacrifice. The memorial dedicated in Guetteville will help, as will the installation of a new window in the church where Father Kobos is believed to have celebrated the first English Mass last June.

As for Father Maternowski’s actions, Father Kobos said: “A dire situation prompts a dire response. He laid everything aside, including his own safety. He went, he met with the medical officer, and he was on his way back. It’s a wonderful story of, dare I say, martyrdom on behalf of broken men.”

Michelle Martin writes from Illinois.