For more than four years, the office of the attorney general in Illinois has been looking into clergy sexual abuse. Prompted into action by the damning report out of Pennsylvania in 2018, then-attorney general Lisa Madigan began an investigation into the six Latin-rite dioceses within Illinois. Once again, as has happened most recently in Maryland and other states, the information discovered is both damning and greatly dismaying. The report shows that, since 1950, hundreds of priests abused nearly two thousand children.

The scourge of clergy sexual abuse is one of the greatest black marks on the Church in its 2,000-year history, and it is necessary to dig the evil up at its roots and bring it to light, for “the truth will set you free” (Jn 8:32).

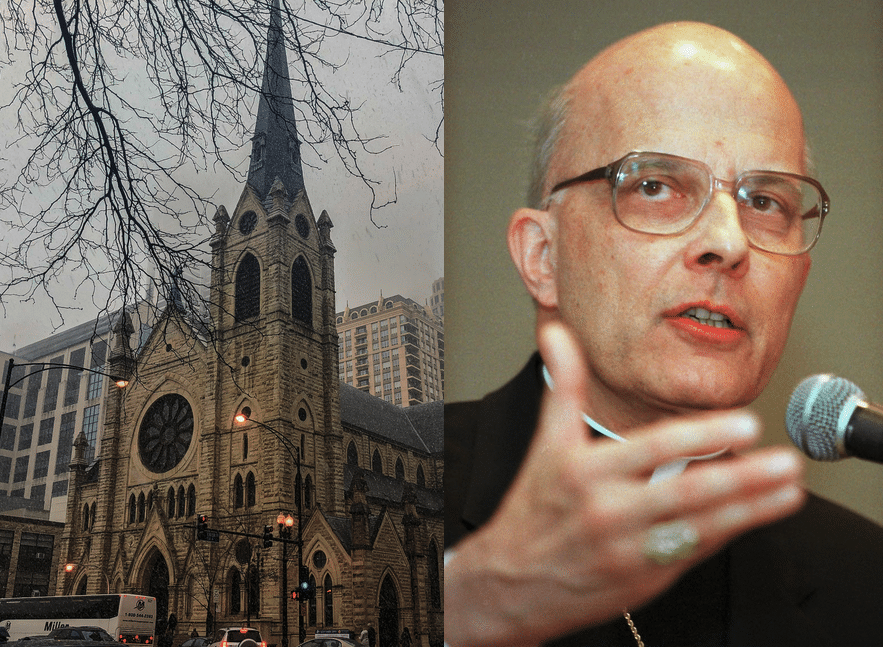

At the same time, it is necessary for the complete truth to be told, not necessarily the convenient one. For the past seven years, I have been immersed in the life of Cardinal Francis E. George, O.M.I., archbishop of Chicago from 1997 until six months before his 2015 death. In the course of my research in writing his first biography that was published earlier this year, I found one of his greatest regrets to have been the discovery that laicized priest and notorious abuser Daniel McCormack had abused children on his watch.

There is no question, as the recently published “Report on Catholic Clergy Child Sex Abuse in Illinois” states, that McCormack “is one of the most infamous child abusers anywhere in Illinois.” And, as the report cited, there is no question that the way allegations were processed by a intricate, multi-layered archdiocesan bureaucracy that manifested a “left-hand-doesn’t-know-what-the-right-hand-is-doing” dysfunction. The report is fair in its criticism of an archdiocesan-wide communication breakdown.

However, the justice intended to be upheld by such a report is ineffective — and its moral authority undercut — due to its incomplete and biased nature. This is certainly the case when it comes to Cardinal George’s role in the McCormack case.

Who was Daniel McCormack?

Daniel McCormack was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of Chicago by Cardinal Joseph Bernardin in 1994. He served in several parishes, including as pastor, and was a dean — a position of leadership — for the archdiocese. When George arrived in Chicago, McCormack had been serving on a seminary faculty — a position that was considered one of trust. He was a popular, energetic young pastor who served poverty-stricken inner-city parishes that welcomed mostly minority families. It is now known that McCormack was living a double life and, in fact, had been involved in sexual misconduct since his days as a seminarian.

What the AG report gets right … and wrong

The attorney general’s report is correct in holding up McCormack as a case study; his serial abuse was truly horrendous, and there were breakdowns on multiple levels. But the report also presents a biased, unjust and false caricature of Cardinal George’s role in the scandal. This approach is undergirded by a breathtaking lack of facts and nuance to back up its claims.

According to the attorney general’s report, the archdiocese did not investigate an initial claim against McCormack in 2003. In a 2008 deposition, however, Cardinal George shared how he had only first heard of the initial complaint after the second arrest of McCormack in early 2006.

George first became aware of allegations of misconduct on the part of McCormack in September 2005, after McCormack’s first arrest for suspected sexual abuse of a minor at the end of August 2005 (George was not told about the arrest until three days after it happened).

When the archdiocesan review board advised McCormack’s removal in October 2005, the attorney general’s report stated that Cardinal George “took no action.” The review board, however, made its recommendation without conclusive evidence. At that point, the U.S. bishops’ Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People and the Church’s code of canon law provided that a priest could be removed only when an accusation had been found credible. The police and the state were not sharing information from their own investigations, and, as far as Cardinal George knew, no victim who was willing to cooperate with a thorough investigation had come forward to the archdiocese.

George, striving to balance “zero tolerance” with the rights of priests, objected to McCormack’s removal knowing that a removal without proper grounds would be a violation of Church law, would cause undue damage if the allegation ended up being false, and could potentially be reversed if the priest appealed to the Holy See. It turns out, however, that George’s desire to follow established norms and procedures, on account of his concern for justice and fairness for all parties, also came at a great cost. He would later say, “I wish that I had followed [the review board’s recommendation] with all my heart.” The Charter is specifically designed to prohibit the diocesan bishop from interfering with an investigation against a priest or deacon of the diocese accused of sexual abuse of a minor, and in this case, that rule worked against George.

Though McCormack was not removed from ministry, he was assigned a priest-monitor following his 2005 arrest — which was then part of standard archdiocesan protocol for accused priests while they were under investigation. But the system, as George put it, “was sorely inadequate,” and it fell apart. Monitoring was sporadic and dependent at times on what information the accused was willing to share. McCormack abused again, and more than one child suffered. After McCormack’s final arrest in January 2006, a conviction followed a guilty plea of five counts against him.

Standing in the breach

The McCormack case illustrates, as the report indicates, a systemic breakdown of communication and collaboration, as well as a lack of competency, within archdiocesan administration. It is arguably the ugliest chapter of Chicago’s clergy sexual abuse crisis, and George could not escape it. But, as evidence shows, he did not downplay it or cover it up. At this point in the Church’s history, however, someone had to stand in the breach and try to do right by all parties, and that’s where George placed himself. “We are sometimes asked to choose between the accuser and the accused,” Cardinal George said when the bishops convened for their abuse summit in Dallas in 2002. “But of course, precisely as bishops, let alone as disciples of the Lord, we cannot choose one or the other; we have to choose both. We have to love both.”

In early 2006, George made an urgent and bold plea in a private memo to priests that if any of them were engaged in nefarious activity (outside the scope of abuse of minors) they should make themselves known. In subsequent weeks and months, there were many priests who, to their credit, went to George, admitted their failings and left public ministry as a result.

In response to the systemic failures of communication in the archdiocese related to the McCormack scandal, George called for a thorough, independent investigation, something of a first in any American diocese. He put chancellor Jimmy Lago in charge of providing for a more comprehensive, effective, and prompt archdiocesan response to clergy sexual abuse. Lago was instrumental in bringing about a report, commissioned by the archdiocese and conducted by former FBI agent Danny Defenbaugh, that detailed a litany of deficiencies in the archdiocese’s process of investigating claims of sexual abuse against minors. This is also believed to be a first for any American diocese.

Defenbaugh’s report identified as a major deficiency the poor flow of communication within the chancery, with Cardinal George often being the last to receive critical information. In an attempt to correct this, especially regarding the sensitive topic of sexual abuse of minors, George asked archdiocesan employees to “come forward directly to me” if they had any information related to the sexual abuse of minors. George also wrote to the director of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), asking that this agency also begin to share information with the archdiocese gleaned from their own investigations of those accused of sexually abusing minors — something that did not happen in McCormack’s case. For example, the archdiocese, including George, had no knowledge that the DCFS had “found credible evidence of child abuse/neglect” against McCormack. McCormack was informed by DCFS of this finding in a Dec. 14, 2005, letter, but this crucial document was not shared with the archdiocese until after the priest’s second arrest. “With all my heart, I wish they had given me this on December the 14th,” George stated in a deposition on the case in 2008 upon seeing the letter for the first time. “They gave it to Dan McCormack. Had they given it to me, he would have been out immediately.” George wrote to his priests, “There is more than irony in the claim that going only to the State will result in immediate action, when quite the contrary happened here.” As he told Chicago priests in 2012, “If there’s any coverup with McCormack, it’s with the civil authorities.”

Amid great criticism against the archdiocese and its archbishop, and in an attempt to set the record straight on the McCormack case — George once noted that the case had revealed a flaw in the Dallas Charter. Because of the ugly episode, the Charter, at George’s instigation, was amended to provide for the temporary removal of a priest while he was under investigation. “In that sense, some good has come out of this evil story,” George wrote.

Cardinal George also regularly met with survivors of clergy sexual abuse, and his honesty and candor in the wake of this scourge on the Church earned him the admiration of many. In 2019, four years after George’s death, an international summit on clergy sexual abuse was held at the Vatican in the wake of another wave of scandals and cover-ups. During testimonies offered by victim-survivors to key members of the hierarchy, Cardinal George was the only bishop mentioned by name, held up as a model of leadership amid the sex scandals plaguing the Church.

The work of getting to the truth of the clergy sexual abuse crisis is critical. But that important service is weakened when it is accomplished by way of partial truths, missing data and a scarcity of nuance. We can and should do — and demand — better for the sake of the very truth we hope to find.