When the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared, still a mile or so away in the distance, near the end of the Calzada de Guadalupe, I could have fallen on my knees right then and there in thanksgiving. My feet hurt, and blisters were forming. Cheap Keds knockoff sneakers were proving radically inadequate to my demands on them. There was a hole in one of them. It had already rained on me twice, and I was soaked to the skin. And then there was the walk home, which was still looming. But none of that mattered. I was almost there. I would see her soon.

Earlier that day, I had stood on the threshold of the Hotel Isabel — a blessedly cheap, slightly shabby, colonial gem in the Centro Historico of Mexico City — letting the noise of the busy street flow past the enormous carved wooden doors into the cool, sleepy exterior. Every evening of my visit up to that point, I had climbed the slightly rickety stairs past each marble tiled floor, up to the brightly painted courtyard open to the sky. I would watch the hazy pink light spread over the city’s sea of endless rooflines. I felt very much alone — and very much unmoored. It had been a rough couple of years for me — for many others. There was no indication that things would get better anytime soon. And yet here, up in the smoky, warm sunset air, I was waiting in the charged electrical air for the release of a thunderclap. Something was coming.

Now, dawdling at the hotel’s entrance, I considered my options. An Uber would be cheap. Most things were cheap in Mexico City at the moment, if you had U.S. dollars to spend and knew where to look. But I was not here primarily as a digital nomad or even, at least for today, as a tourist: I was a pilgrim. And while the line between the two often blurs, one thing was clear to me: Tourists take Ubers. Pilgrims walk. And so off I set in the hot, muggy sunshine, on the five-ish mile road to Tepeyac.

My decision to be a pilgrim was a little haphazard, a little capricious. I had been sitting on my family’s couch a few days after Christmas, unattached, newly a freelancer, wondering how best to use my newfound freedom in planning vacation time, trying not to peek over the edge of the abyss marked by the big neon sign flashing “No guaranteed monthly income.” I clicked around on the internet for various countries’ COVID-19 management protocols. It was not an encouraging exercise. Two years later, it felt as if the world was still emerging from the shadow of those first early weeks of 2020: too many sirens, scenes of bodybags playing on the news, panic and closures. I was afraid of uncertainty — not the mere uncertainty of fortune’s ups and downs, but of the regulation of movement, of changing rules, of sudden shutdowns, of the inevitable personal misstep that would land me in some sort of liminal bureaucratic nightmare. Finally, I searched: “easiest places to visit COVID 2022.” Mexico and Greece were consistently at the top of the list. I felt I owed my own continent the honor of a first visit; besides, it would be cheaper. Mexico it was.

It was not until my first night under the high ceiling of my hotel bedroom, trying to tempt a breeze in through the tall wooden windows in the absence of air-conditioning, that I sat bolt upright in bed and understood. I knew what I was doing here. I knew why I was in Mexico. I had to see her.

The story of Our Lady of Guadalupe

The “her” I needed to see was Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The story of Our Lady of Guadalupe is one every Catholic school child learns sooner or later. Ten years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, on Dec. 9, 1531, one Chichimec peasant named Juan Diego was passing the hill of Tepeyac on his way home from religious instruction. He saw her. Robed in cerulean, covered with stars, the sun behind her, the moon under her feet, the young pregnant women with dark eyes and skin and hair spoke to him in his own Nahuatl language; she announced herself as the mother of the true God.

She said she desired a chapel to be built on the hill and asked him to present himself to the Archbishop of Mexico. Juan Diego did as she asked. The bishop sent him away. Again, the lady appeared; again, she asked him to keep insisting. This time, the archbishop humored Juan Diego; he asked him to tell the lady to send him back with a truly miraculous sign. The lady promised to provide it the next day, on Dec. 11.

But Juan Diego did not meet with the lady on Monday. His uncle had fallen gravely ill, and Juan Diego would not leave his bedside until the time came to summon a priest. In one of the tale’s most human moments, ashamed and evasive, on Dec. 12, he went the long way around to avoid meeting the lady. But she found him where he was. Gently scolding him, she spoke those heart-stopping words: “Am I not here, I who am your Mother?

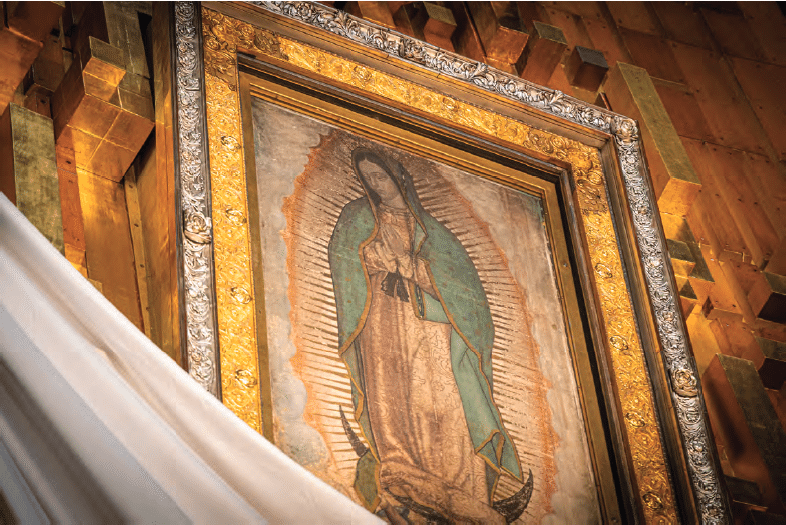

His uncle had recovered, she told him. Meanwhile, he was to gather the Castilian roses that were inexplicably growing in the barren December ground and present them to the archbishop. But when he arrived at the episcopal residence and opened his tilma, a rough cloak woven of maguey fibers, nobody was looking at the roses that tumbled out. Unbeknownst to Juan Diego, an image of the lady, dazzlingly beautiful and impossibly perfect, had been imprinted on the cloak. It still hangs today, 500 years later, in the basilica at Tepeyac, and 20 million people come to pay homage every year. In the meantime, Our Lady of Guadalupe has become known and loved as few other Marian titles have. You will find her image in high and low places, painted in magnificent churches and printed on cheap T-shirts, adorning homes and taco stands and car dashboards. She is especially beloved by those in most need of her promise: “Am I not here, I who am your Mother?” Migrants at the border invoke her protection. In August 2022, a few months after my visit, United Farmworkers striking in protest of California labor laws carried her banner. She is truly the mother of the Americas.

Faith in the miracle

I pondered the story as I trudged my long way up the Calzada de Guadalupe, past friendly street dogs and gated courtyards and cavernous auto body shops. It is not without its critics. Some take issue with the fact that the Nican Mopuah, a Nahuatl manuscript, one of the earliest recountings of the miracles, is not corroborated by any contemporary account from the Spanish archbishop involved. Too much oral history precedes historical documentation for these skeptics. Another line of criticism, one I heard from an art historian friend, involves the stylistic similarities between the image imprinted on Juan Diego’s tilma and traditional European madonnas of the early modern period. To my friend’s mind, the fact that the image is recognizable within a European tradition means that it is likely to be the work of human hands.

The facts of this particular criticism have never bothered me. To me, they suggest that enculturation — the process by which the universalities of the Christian faith are presented to us in the familiar trappings of our own culture — was as much a necessity for the Spaniards as it was for the indigenous people they conquered. Much is often made of the fact that Our Lady spoke Nahuatl, that she appeared where there had once been a shrine to the Aztec goddess Tonantzin, that she was dark skinned and appeared as a beautiful young indigenous woman. And indeed, these are some of the most beautiful parts of the story. But the gracious condescension with which the Queen of Heaven appears in the inadequate trappings of particular human cultures was as much a favor granted to the particular, contingent culture of the Europeans as to that of the Nahua. When Our Lady of Guadalupe revealed herself to Archbishop Juan de Zumarraga, she sent him the roses of his native homeland and a version of herself he could recognize immediately. Even the name Guadalupe is a name of mixture and unity, connoting both the earlier shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Extremadura, Spain, and various possible Nahuatl titles: Tecuantlaxopeuh (she who banishes those who devoured us) and Coatlaxopeuh (she who crushes the serpent).

But the miracle of Our Lady of Guadalupe requires, in the end, the heart’s assent, even if ecclesiastically approved, for there are good faith disagreements about the various kinds of evidence involved. For my part, I am happy to admit that my reading of the controversies is strongly influenced by the disposition of my heart: I have loved the story from the first time I heard it, from the instantaneous decision that Our Lady of Guadalupe would be the patron of my middle name, Marie. I loved Juan Diego’s shame-faced avoidance, and I cherished the virgin’s caress of a rebuke — “Am I not your mother?” I loved to look at the richness of that spangled cerulean robe, as if the ocean and sky itself had draped themselves around this woman from heaven. But most of all, I loved thinking about the cascade of rich, velvety, heady-smelling Castilian roses, gathered from dead, barren earth in defiance of seasonal laws.

Life and death

Life coming out of death is, in one sense, not so unusual: It is the slow, grinding, cycle of decay and metabolism that the entire organic world teaches us, year after year. But the roses on the hill of Tepeyac were not the normal story of wintry decay feeding springtime life, as hopeful as that story can be. The roses out of barren winter ground are not a natural picture but an impossibility, a riddle, a meeting of opposites. They are not delicate and discreet snowdrops, not the promise of spring to come, but the full gaudy riches of high summer erupting through the height of winter. They do not represent death eventually giving way to new life; instead they are a vision of death itself being changed all at once, in the twinkling of an eye, into impossibly exuberant, abundant life.

Roses in December are what Mary has been to the Church ever since, at the foot of the cross, we were told, “Behold your mother.” The time of incomparable desolation was also the moment of a gift whose sweetness would linger in the air for millennia. Since then, our mother has been the dispenser of gifts and the portal to glory who delights in being unearned, unexpected, improbable, out of season. She was the first to say “the almighty has done great things for me,” and she covers us in the glory of her mantle as we wait to be changed into something approximating her generosity, her gratitude, her trust.

Life-in-death is the profane shadow of the erupting glory of the lady from heaven’s roses in December, and it hangs in the air in Mexico City. It has hung there for a very long time. When the blood of the Aztec empire’s human sacrifices ended, the cruelty and tyrannies of the Spanish who replaced them began — with effects that echo to this day. And out of all this death and destruction came the shrine at Tepeyac hill, came the shared Spanish and indigenous heritage from which most Mexicans descend, came a new faith on a very old continent, and came the greatest city of the Americas: Mexico City, vast and always expanding, with volcanoes on the horizon, with the rooflines infinite, the wrought-iron balconies gracious, and the air filled with smog, with honking horns, with hustle and electricity.

You can sense the life-in-death as soon as you enter Tepito, the barrio bravo, one of Mexico City’s famously poor and rough neighborhoods, to which its residents are nonetheless scrappily (and in my opinion, deservedly) proud to belong. Every day except Tuesday, the streets are filled with a tianguis, an open-air market where, if you really want to, you could probably buy just about anything. I wanted to buy a michelada. I strolled around sipping it, listening to the vendors ply their wares, the old women chatting in little groups anywhere they could sit, the perennial hum of the motorbikes. An etching of Our Lady of Guadalupe smiled down at us from a wall.

Among the Tepito tianguis, you hear regular offers to buy cocaine, or this or that drug. The drugs are supplied by the cartels, whose fighting with the government and with each other has left at least 39,000 bodies unidentified in morgues, the Guardian reported in 2020. The cartels are also linked to the cult of Santa Muerte, whose shrine I was visiting that day. Santa Muerte is perhaps the inverse of Our Lady of Guadalupe. She is La Flaquita, “the skinny one,” while Our Lady reveals herself slightly rounded, pregnant with the saving promise of her son. Behind the glass of the shrine, La Flaquita’s skeletal face and body are clothed in gold — not the gold of the sun, but of money, which people leave her. She is the competing inverse of Our Lady of Guadalupe’s miraculous life out of death; she is death-in-life, the promise of a good life, of money, of protection, of wrongs righted, if only you let sacred death rule you while you walk through this world.

Seeing our mother

I thought about Santa Muerte as I finally reached the basilica on tired feet. I thought about her as I walked through the bustle of items for sale in the wide street below the final ascent of the basilica, a multi-colored jumble as cheerfully committed to mixing sacred and profane as any medieval pilgrimage sight. I thought about her as I kept ascending, past the main basilica to the very top of the hill, where the original chapel lies. Breathless, I drank an iced drink for sale at the midway point and looked over the city. How had Juan Diego felt, climbing this summit? The rooflines were still endless, but I was no longer unmoored or alone. I knew what I was doing here, and that was enough for now. When I entered the chapel, one of the smallest chapels in the whole magnificent complex, the murals of Fernando Leal greeted me. In seven frescoes, the artist tells the entire story of Juan Diego’s encounter with the Mother of God. In my favorite, Our Lady of Guadalupe is shown appearing to the bedridden uncle of Juan Diego, while a skinny, skeletal figure flees and cowers in the corner. I did not think about Santa Muerte anymore while descending those steps.

In the main basilica, I fingered the jotted down list of people I had promised to pray for, most of them solicited last minute on social media. I passed people who were crawling into the basilica to hear Mass on their knees. Where did I get the idea that my knockoff Keds and my five-mile walk made me such a bigshot? I waited till the end of Mass and got in line to see the tilma.

When you see the tilma, you pass underneath it on a sort of human conveyor belt. You have time to look, but the whole process is very mundane and a little ridiculous. But at the time, I was not thinking about this. I was queuing up for a second turn on the conveyor belt, resolved to do anything I had to do in order to keep looking at that face, where a love like I had never seen looked down on me. The tilma is miraculous, but the love that emanates from it cannot be explained in terms of its physical properties. I had forgotten La Flaquita, forgotten COVID, forgotten my directionless and increasingly precarious freelancer situation, forgotten everything except that face. I could look at that face for the rest of my life, and it would never be enough.

I cannot look at that face for the rest of my life, but in the intervening months, I have known that I am tucked in the folds of my mother’s mantle, come outward trial and inward failure. Someday, if I am so blessed, holy death will overtake me, and with my own eyes I will see the gate of heaven.