For the first time since Gallup began polling on the topic of religion, those who say they belong to a church, synagogue, mosque or congregation are now a minority in America. When Gallup first asked the question in 1990, 70% of all Americans indicated they belong to a house of worship. Now only 47% do, a seismic shift in the sentiments — and the religious commitments of the country.

What’s more, one in three young adults indicated that they claim no religious affiliation at all. Since 2000, there’s been an overall rise in those who say they don’t identify with any religion — from 8% to 21%.

Against this remarkable detachment from religious identity, an interesting dynamic has emerged: the religiously unaffiliated are increasingly serving as activists and leaders in movements for social change and justice.

Historically, social justice initiatives gained momentum and strength from those who were motivated by their religious convictions (think of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, Dorothy Day and Desmond Tutu). But it is equally true that such religious beliefs are not necessary for participation in causes that defend human rights and dignity and oppose the mistreatment of the vulnerable.

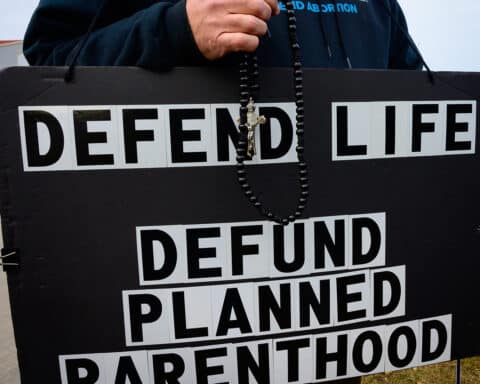

Today’s modern effort to reinstate legal protection for unborn children includes secular humanists, atheists, agnostics and otherwise non-religious people. To the surprise of much of the media, non-religious pro-life advocates have claimed an increasing presence in the pro-life movement despite being met with skepticism or being told they don’t exist. When powerful national newspapers, like the New York Times, assert that the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision was based on “religious doctrine,” and that religious people have imposed their belief system on the entire country, they ignore the voices and views of many Americans who have no “belief system” other than science.

Secular news outlet National Public Radio likewise concluded that “when life begins is essentially a religious question” — eliminating debate or discussion of abortion on other grounds. Pigeonholing abortion as a religious question was even apparent during oral arguments in Dobbs, the Mississippi case that overturned Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor pressed Solicitor General Scott Stuart: “The issue of when life begins has been hotly debated by philosophers since the beginning of time. It’s still debated in religions. So when you say this is the only right that takes away from the state the ability to protect a life, that’s a religious view, isn’t it? It assumes that a fetus is life at … when?”

Yet, religious leaders including Pope Francis, who studied chemistry following his graduation from high school, disagree. “For me the deformation in the understanding of abortion is born mainly in considering it a religious issue,” he wrote in a 2019 letter to an Argentine priest. “The issue of abortion is not essentially religious. It is a human problem prior to any religious option. The abortion issue must be addressed scientifically,” he noted (even underlining the word “scientifically.”).

Along with the pope, the “nones” don’t believe the question of when human life begins is a religious one. Groups like Secular Pro-life (headed by an atheist), Rehumanize International (also atheist), the Equal Rights Institute and the Progressive Anti-Abortion Uprising (PAUU) follow the science: the clear, long-established medical fact that human life begins at the moment of conception.

Medical textbook “Human Embryology & Teratology” agrees: “Fertilization is an important landmark, because under ordinary circumstances, a new, genetically distinct human organism is thereby formed,” the textbook notes. And a recent survey of thousands of biologists from across the globe found that 96% likewise affirmed that human life begins at fertilization.

“You absolutely do not need to believe in a God to oppose the intentional taking of human life,” insists Herb Geraghty, executive director of Rehumanize. “Many atheists, like myself, who embrace a consistent ethic of life, oppose abortion for the same reasons we oppose things like the death penalty, war and police brutality. Abortion is a human rights violation, and everyone should be working to end it.”

Non-religious anti-abortion organizations embrace this scientific consensus, adding to it a human rights component and a desire to advocate for the most vulnerable human lives “at the margins.” These secular groups may have many different perspectives on other hot-button social issues than their mainline Christian colleagues, but all agree with the basic pro-life premise that every human life is worthy of protection, at all stages of development.

“As an atheist, I believe the life we have now is the only one we get,” said Monica Snyder, executive director of Secular Pro-Life. “I’m against abortion because it destroys humans. This is not a religious belief; it is a fact of biology. As organisms, we begin as zygotes. You, me, and every person we know was once an embryo, once a fetus. It is those who defend elective abortion who want to make this debate about religion, because biology doesn’t support the pro-choice position at all.”

Even after 50 years as “settled law,” Roe v. Wade never really settled into the hearts and minds of the American people. It may be easier to dismiss pro-life advocacy as belonging to the pages of Scripture or the stuff of Sunday sermons than to engage the scientific or human rights questions, but the growing presence of non-believers who worked (but didn’t pray) to see Roe overturned speaks to one of the principal tenets of our country’s founding: that every human being has natural rights, present by virtue of his or her very humanity.

Mary FioRito is an attorney and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and the deNicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame.