The following essay was selected as the winner of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ first-ever religious liberty essay contest on the theme “Witnesses to Freedom.” The essay contest was co-sponsored by the OSV Institute for Catholic Innovation. For her winning essay, Elizabeth Bernadette Rudolph was awarded a $2,000 scholarship.

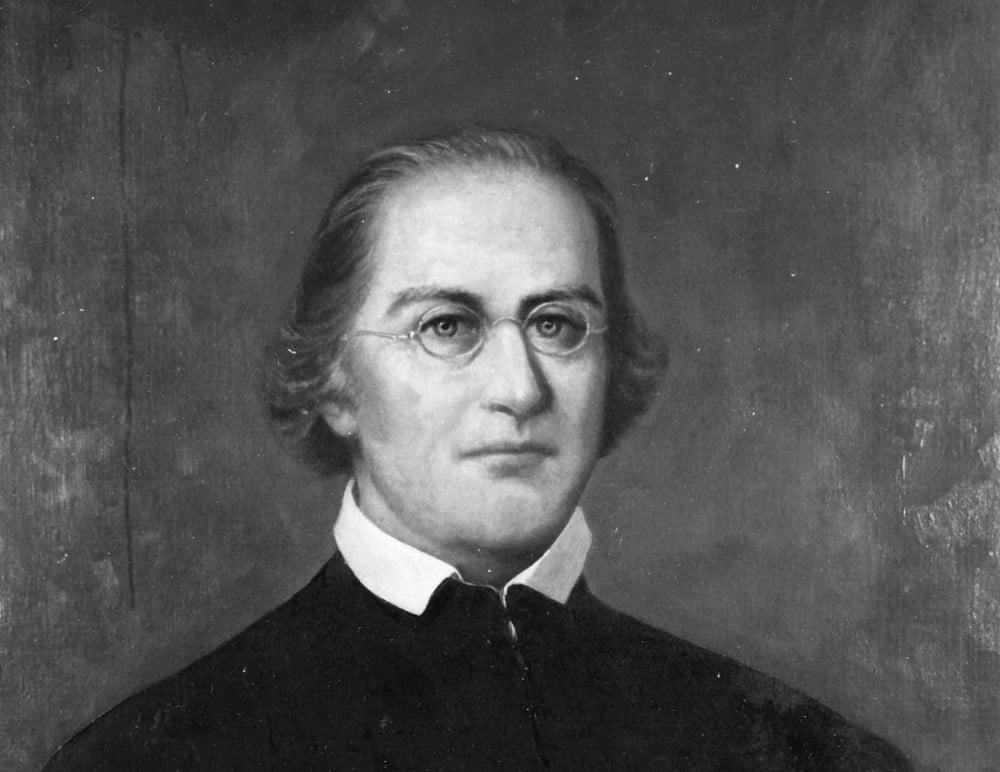

Anthony Kohlmann was born in France in 1771. He was ordained as a Jesuit priest in 1796, and he entered the Society of Jesus. He then went to the United States to aid in missionary activity and to teach seminarians. In New York, Father Kohlmann helped initiate the building of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and founded two schools and an orphanage. But this is not what Father Kohlmann was to be remembered for.

In 1813, Father Kohlmann’s dedication to the beliefs and practices of the Catholic faith were challenged. This began when James Keating, a parishioner of Kohlmann’s church, accused Daniel and Mary Phillips of having received stolen goods. However, Keating tried to drop the charges when the goods were returned with Father Kohlmann, his pastor, as a mediator. Officers were suspicious of Keating’s sudden determination to drop the charges, so they questioned Keating and learned how the goods had been returned. They then called Father Kohlmann in for questioning.

Father Kohlmann refused to give evidence about who had received the goods because he had learned of the crime during confession and did not want to break the seal of confession. The ecclesiastical law of the seal of confession, according to an article by Catholic apologist Trent Horn at catholic.com, is that “it is absolutely forbidden for a confessor to betray in any way a penitent in words or in any manner and for any reason.” Breaking the seal of confession immediately leads to excommunication from the Catholic Church, and reinstatement can only be granted by the pope.

Father Kohlmann was asked by the officers direct questions about who the person was, and more indirect ones, like whether the penitent was male or female or of what race they were. He respectfully refused to give any information at all. The case was sent to the grand jury, and Father Kohlmann was summoned to court.

Father Kohlmann assured the court that, in a personal, not professional capacity, he knew nothing of the crime or who committed it. He said that if he had been called to court based on what he knew unprofessionally, not in his status as a confessor, he would have been compelled by his religion to “respect and obey” civil law and to “declare whatever knowledge [he] might have,” according to William Sampson’s 1813 book “The Catholic Question in America.” However, as a minister of the Sacrament of Reconciliation, he could not disclose any information about the penitent because it would make him, in his words, “a traitor to my Church, to my sacred ministry and to my God.” He assured the court several times that he was not refusing to give evidence out of disrespect for civil law or for the court, but only because his faith compelled him not to.

Father Kohlmann then outlined the things that would happen to him should he reject this part of his faith: He would degrade himself in the eye of the Church; he would be stripped of his position as a priest; he would be “lodged in close confinement, shut up between four walls to do penance during the remainder of my life,” according to Sampson, and he would feel himself guilty of eternal damnation after death.

Sampson was a lawyer who had fought for religious liberty for years. Sampson pointed out that, even in Ireland, where Catholics had few rights at all, priests were not compelled to use as evidence something that they had been told in confession. The court unanimously voted in support of Father Kohlmann.

The mayor of New York, DeWitt Clinton, wrote the opinion of the court, stating that, because the free exercise of religion is protected by the Constitution of the United States, its “ceremonies as well as its essentials should be protected,” and that the sacraments in a religion are an essential part of it; therefore, the right to engage in the sacraments of a religion are also protected, Sampson wrote. Clinton went on to remark upon the difficult situation in which Father Kohlmann had been put: If he had followed the urges of civil law and given evidence, he would have been excommunicated, but if he had lied about the penitent, he would have been committing perjury. He had been put in a situation in which simply remaining silent was the best decision, and the only situation that did not involve serious moral questions.

In his opinion, Clinton expressed the fear that requiring a priest to give evidence in such a case would be seen as state coercion against a religious denomination. He pointed out that, although Protestants do not have confession, they have baptism and the Eucharist, and if the state tried to coerce something that violated one of their sacraments, that would be obviously against the right to free exercise of religion. That the court recognized that the case was based on freedom of religion and not “merely the protection of the minority or a conscience protection,” was extremely important, because any other form of protection would have belittled the importance of the seal of confession. Clinton concluded that “until men under the pretext of religion, act counter to the fundamental principles of morality and endanger the well-being of the state, they are to be protected in the free exercise of their religion,” according to Sampson. The case was closed, the right to free exercise of religion was protected, and the law of the seal of confession was upheld.

This court case led directly to a New York law 15 years later that stated that, in court, no priest of any denomination would be compelled to disclose information heard in confession.

Father Anthony Kohlmann’s example is one that every person of every religion should look up to. His dedication to the freedom to exercise his Catholic faith is admirable and inspirational. Everybody can follow his lead by standing up for their own religious freedom, even if it is simply by praying before a meal in public. This act, although small, is a way to recall the freedom to exercise religion to the forefront of the minds of the people around them.

As a Catholic in a time of extreme anti-Catholic sentiments, he was able to open the eyes of a jury of Protestants and show them the importance of respecting his freedom to exercise his religion. By following Father Kohlmann’s example, all people can respect the freedom of religion of those around them and feel free to exercise their own religion fearlessly.

Elizabeth Bernadette Rudolph writes from Tomball, Texas.

| RELIGIOUS FREEDOM WEEK 2022 |

|---|

|

Beginning June 22, the feast of Sts. Thomas More and John Fisher, the USCCB invites Catholics to pray, reflect, and act to promote religious freedom during its 2022 Religious Freedom Week. The theme of this year’s celebration is “Life and Dignity for All.” For more resources on Religious Freedom Week, visit USCCB.org. |