When Jesus appeared to St. Faustina Kowalska and spoke to her of his unfathomable mercy and inexhaustible compassion, it was nothing new. The heart of the Gospel message has always been that God in his mercy runs after sinners to bring them back to himself.

But just because it’s old news doesn’t mean it’s not good news — or necessary news. Because while we know that Jesus pours out mercy in abundance for even the worst of sinners, we still refuse to believe. We refuse to believe that mercy is on offer to us in our sin, and we refuse to believe that God’s mercy could extend to those people we most love to hate. And so the Church reminds us again and again of God’s boundless mercy, showing us saints whose sins were appalling: Blessed Bartolo Longo, the Satanic high priest; St. Olga of Kiev, the mass murderer; St. Bruno Sserunkuuma, the violent bigamist; St. Longinus, the Roman soldier who nailed God to the cross.

These stories call to us in our despair, reminding us that there is nothing we can do that God won’t forgive. And so we bring him our sinfulness and our brokenness and he offers us only mercy and grace, washing us clean by his blood spilled on Calvary.

Still, we who have received God’s mercy often find a way to become stingy with this gift offered to us in abundance. Or perhaps we don’t begrudge anyone the mercy of God, we just don’t see it as our job to do anything about it. We pay our taxes, put up with our in-laws, and go to Mass on Sundays, congratulating ourselves on our virtue while ignoring the Great Commission to go into all the world offering the mercy of God to the lost and the broken.

Again, the Church calls us to more through the lives of the saints, through one person after another who experienced the mercy of God and knew he had to bring that mercy to the world. When we hear these stories, we begin to realize that the call to go out to all the world and tell the good news extends not just to distant pagan nations but to people whose politics or sexual ethics or line of work or personalities makes us inclined to despise or disdain them. As we rejoice in the gift of Divine Mercy, let’s learn about these saints who brought mercy to those least aware they needed it — or most convinced they didn’t deserve it. Let’s allow their witness to call us to be missionaries of mercy in our own lives.

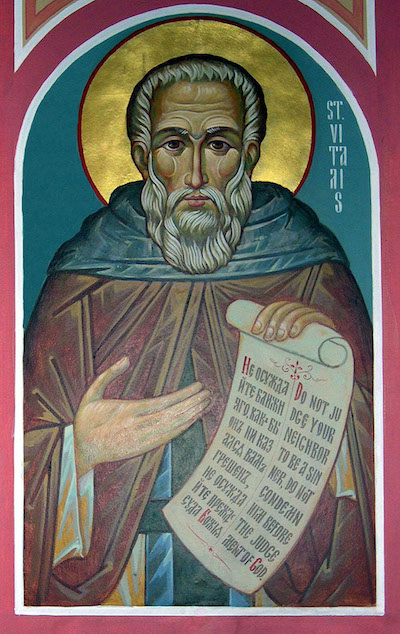

St. Vitalis of Gaza

St. Vitalis of Gaza (d. 625) spent every night with a different prostitute. We hear a claim like this and settle in for a great conversion story, but this isn’t the “before” of Vitalis’s story. This is what holiness looked like for him. A hermit who had spent decades in the desert, late in life Vitalis moved to Alexandria, where he spent his days working grueling jobs so that he could spend each night in a brothel.

The Christians of Alexandria were scandalized, but despite their complaints and criticism, Vitalis ignored them. Ultimately, Vitalis was killed in the street; when his body was found, he was clutching a scrap of paper with 1 Corinthians 4:5 on it: “Therefore, do not make any judgment before the appointed time, until the Lord comes, for he will bring to light what is hidden in darkness and will manifest the motives of our hearts.” The Christians who had lambasted him must have been bemused by his clinging to this verse, but they had already passed judgment: Vitalis was a fallen monk, and now it was too late for him to repent.

He offered them the mercy flowing from the wounded side of Christ, unconcerned that in doing so he would become as despised as they. They were worth it, after all.

But the disgraced cleric’s funeral was packed, filled with dozens (perhaps hundreds) of former prostitutes who wept over their loss. It seems that Vitalis hadn’t actually spent time with them out of lust. He had left the silence and peace of the desert to run after the lost sheep of the city, to come looking for each individual woman who had been so used and wounded. Every night, he had walked into a different woman’s room, offering her money for the evening with only one request: that she not touch him. When each baffled woman asked what he meant, he told her: He wasn’t there to use her. He wanted to buy her one night of freedom, one night without sin. And when they asked why, Vitalis would tell them: because they were loved. Because Jesus died to save them. Because they were worth more than what they’d done or what had been done to them.

He would talk to them and listen, pray for them and pray with them. And when they were ready, he would help them get out. He’d find homes for them, dowries, even husbands or monasteries. All at the cost of his reputation and ultimately his life.

In a world that wrote these women off as fallen, that used and abused them and then despised them for it, Vitalis saw them. He saw them and loved them, and, like the Good Shepherd he’d modeled his life on, he went out to get them and bring them home. He offered them the mercy flowing from the wounded side of Christ, unconcerned that in doing so he would become as despised as they. They were worth it, after all.

St. Joseph Cafasso

St. Joseph Cafasso (1811-60) loved hardened sinners. He loved the angriest, cruelest, most violent criminals. And he loved them enough to risk his life by walking right into their cells and asking them to repent.

A small, sickly man, Cafasso’s heart was fixed on holiness from his earliest childhood. His virtue was so evident that after Cafasso’s ordination, his young friend St. John Bosco chose Cafasso for his spiritual director. But Father Cafasso didn’t just appeal to the already holy. He had a way of speaking about the mercy of God that softened even the hardest hearts.

On one occasion, a group of prisoners he had been preparing for confession became reluctant to bite the bullet and lay their sins bare before the cross. Father Cafasso walked right up to the largest man there, took him by the beard, and said, “I will not let go until you go to confession.” The man protested, then consented (awkwardly). Within a few moments he could be heard weeping in relief; when he returned to the group, he insisted to his friends that he had never been so happy in all his life. He was so eloquent in singing the praises of the sacrament that he persuaded all the other prisoners to go and Father Cafasso spent hours hearing confessions.

When criminals were in such despair of God’s mercy that they were on the point of killing themselves, the wardens called Father Cafasso. When the dying obstinately refused the sacrament, their families called Father Cafasso. And every time, he would gently persuade them, though at first they might rage and shout. Over the course of his ministry, Father Cafasso was blessed to work with 68 men who were destined for the gallows; each one died penitent, having made his confession and received the Blessed Sacrament. Father Cafasso would go with them all the way to their execution, holding a crucifix up before them and promising them heaven, insisting that God’s mercy was greater than whatever they had done.

Father Cafasso poured his heart into criminals whom the world had written off, but the mercy he offered was available to any who sought it (and sometimes even those who didn’t). He insisted to his fellow priests that they had an obligation to be Christlike in the confessional, writing, “When we hear Confessions, our Lord wants us to be loving and compassionate, to be fatherly towards all who come to us, without reference to who they are or what they have done. If we repel anybody, if any soul is lost through our fault, we shall be held to account — their blood will be upon our hands.”

Though he never downplayed a sin, neither did he berate the sinner. Instead he pleaded, earnestly begging God’s children to come home — even when he did so at great personal risk, surrounded as he often was by dangerous men. But Father Cafasso knew that his mission was worth any risk, and so he spent himself utterly to shower Divine Mercy on anyone who would receive it.

| THE MERCY CALL OF ALL THE BAPTIZED |

|---|

|

“‘Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good; for his mercy endures for ever!’ (Ps 117: 1). “Let us make our own the Psalmist’s exclamation which we sang in the Responsorial Psalm: the Lord’s mercy endures for ever! In order to understand thoroughly the truth of these words, let us be led by the liturgy to the heart of the event of salvation, which unites Christ’s Death and Resurrection with our lives and with the world’s history. This miracle of mercy has radically changed humanity’s destiny. It is a miracle in which is unfolded the fullness of the love of the Father who, for our redemption, does not even draw back before the sacrifice of his Only-begotten Son. “In the humiliated and suffering Christ, believers and non-believers can admire a surprising solidarity, which binds him to our human condition beyond all imaginable measure. The Cross, even after the Resurrection of the Son of God, ‘speaks and never ceases to speak of God the Father, who is absolutely faithful to his eternal love for man. … Believing in this love means believing in mercy’ (Dives in misericordia, n. 7). “Let us thank the Lord for his love, which is stronger than death and sin. It is revealed and put into practice as mercy in our daily lives, and prompts every person in turn to have ‘mercy’ towards the Crucified One. Is not loving God and loving one’s neighbor and even one’s ‘enemies’, after Jesus’ example, the programme of life of every baptized person and of the whole Church?” — Pope St. John Paul II, homily for Divine Mercy Sunday, April 22, 2001 |

Blessed Anna Maria Adorni

The life of Blessed Anna Maria Adorni (1805-93) was plagued by grief. She buried her mother, then her first baby. Her second child was healthy, but his birth was followed by nearly a decade of secondary infertility before she finally bore four more children in quick succession, burying one of these shortly after birth as well. Finally, after 18 years of marriage, Anna Maria lost her husband. And still she trusted in God’s goodness. Still she trusted in his love. Against all odds, she still wanted to lead people to him.

As a single mother of four, Anna Maria would have been well within her rights to hunker down and just try to survive. If she was going to be radically generous, perhaps she could serve other mothers or nurture other small children. Instead, Anna Maria went into women’s prisons, offering the mercy of Jesus to the ignored and despised, pleading with the unrepentant to return to the Lord and demonstrating his love to those who felt unlovable. She brought friends with her, persuading her upper class peers that incarcerated women had dignity and so transforming the atmosphere of the prison that a warden observed, “That lady has changed the prison into a monastery!”

Over the course of her life, she lost nearly everything that could matter to a person — except her sense of conviction that the mercy of God was for everyone, that these women deserved it every bit as much as she did.

Even this wasn’t enough. Anna Maria began to see how most women’s suffering became even worse after their release. So she rented homes to serve as halfway houses (if halfway houses were run like convents) and finally moved in with the recently released inmates herself, bringing along her 10-year-old daughter, who was her only child still living at home.

As this work continued, Anna Maria began to reach out to women who hadn’t (yet) been arrested. She walked the streets building relationships with women at risk of turning to crime and found homes for them, too. For 13 years, Anna Maria did this work as a laywoman. During that time, she buried her children one after another until only one son remained. Grief was her constant companion, but her work brought her deep joy. Finally, she founded a religious order so that the women who had joined her in this work could have the stability of vowed life as they continued to serve these people the world had written off.

She did all this at the expense of her reputation and many of her relationships. Over the course of her life, she lost nearly everything that could matter to a person — except her sense of conviction that the mercy of God was for everyone, that these women deserved it every bit as much as she did. When her cause was opened for canonization, her postulator called her “the mother of the marginalized, exploited, of all who are subject to new forms of slavery and, in particular, of the incarcerated and women offended in their human dignity.”

St. Charles Lwanga

Mercy isn’t just about the distant other — the stranger, the victim, even the criminal who we can choose to interact with out of our own generosity. Some of us are called to seek out incarcerated people or people living with addiction, strippers or deadbeat parents, to seek out strangers who are far from Jesus and invite them to say, “Jesus, I trust in you.”

But every one of us is called to love the unlovable people in our own lives, the insufferable coworker, the judgmental sibling, the anti-Catholic neighbor, the snippy spouse. And while sometimes that love has to be from a distance, with boundaries in place so that we can be safe, often the radical mercy we’re asked to offer is courageous love that gently calls people back to Jesus. This mercy says, “I love you. And I’m not going anywhere. But your wife deserves better than that.” Or, “You were made for more than that.” Or perhaps, “You can always come home.”

This is where St. Charles Lwanga (1860-86) excelled. Best known for his leadership of a whole group of young pages at the palace of the predatory king of Buganda, Charles was more than just a leader of all — he was a friend to each. Lwanga had been raised to be a pagan priest and to that end had committed to remain celibate. When he arrived at the court of the king of Uganda, he encountered St. Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe and St. John Mary Muzeeyi, whose love of celibacy mirrored his own. Drawn by their witness, Lwanga began to study the Faith; after Balikuddembe’s death, Lwanga was baptized and took his place as leader of the Christian community in the palace.

He was charismatic and athletic, a favorite of all he met. But he wasn’t one to hoard his social capital; instead, Lwanga went looking for those the world rejected. Chief among these was St. Gyavira, another boy who had been raised to be a pagan priest. Gyavira was promised to the leopard-god Mayanja, and the other pages at court were afraid of him. But Lwanga wasn’t afraid. He and the Catholic pages befriended the lonely young man, and through their friendship they called him to sainthood. When Lwanga began to tell Gyavira about Jesus, Gyavira listened at first because of their friendship. But soon he saw that Lwanga, too, had planned to serve another god and had left his plans behind to follow the true God. Lwanga understood the cost of discipleship for Gyavira, who had been raised to expect women and wealth because of his role as a pagan priest.

Gradually, Gyavira came to embrace the Faith, despite his father’s rage. Though it made him an outcast from his clan, Gyavira burned all the instruments of witchcraft that he owned and began to prepare for baptism. And when the king ordered the death of the Christians at court, Gyavira stood beside his friend Lwanga and joined him in martyrdom.

But Lwanga didn’t only appeal to pagans, inviting them to come to Jesus. He did what’s often harder: called Christians back.

St. Bruno Sserunkuuma was an arrogant, violent, stubborn man before he was baptized. And since baptism isn’t magical, those tendencies remained even after he was a Christian. For some time after his baptism, Sserunkuuma fought against his baser nature. But he still used extortion when his work as a royal guard required him to collect taxes. And when Ugandan King Kabaka Mwanga gave him two young women as a sort of prize, Sserunkuuma’s attempts at chastity went out the window. He took them both as his wives (though neither was a valid marriage), and soon one of the women was pregnant.

Mercifully, Sserunkuuma wasn’t a Christian in a vacuum. His friends St. Charles Lwanga and St. Andrew Kaggwa were disturbed at his behavior and confronted him, issuing fraternal correction so convicting that Sserunkuuma separated from both women. He left them in his home and made something of a monastic cell for himself in the palace, where he lived after making a good confession. Because his friends had spoken firmly but lovingly to him about the man he was called to be, Sserunkuuma was living for Christ and he was ready to die for Christ. Though he wasn’t arrested for his faith, he confessed himself a Christian just the same and was killed alongside Kaggwa and Lwanga, men whose love of Divine Mercy had led them to risk their friendship to save a friend.

Blessed Sandra Sabattini

Blessed Sandra Sabattini (1961-84) was a beautiful, outgoing, intelligent woman with a loving fiancé. But she spent her time serving addicts, people disdained by the world because of their struggle with substance abuse.

Sandra had been a generous and faith-filled child. At only 13 she went on a trip to serve disabled children and found herself changed; though the week was exhausting, Sandra knew she had to continue seeking out the suffering and rejected.

Many people find the innocence of disabled children appealing, but young Sandra wasn’t drawn only to sweet children. She wanted to serve those who suffered, whatever the cause. And so she became more vocal about the plight of the poor and more devoted to serving people living in poverty. But when Sandra was 20, she began to serve a far less “desirable” group: people who were addicted to drugs. Sandra was unusual in her love for people dealing with addiction, her sympathy for their struggle and her desire to be in relationship with them. Nor was she the product of a culture that understood addiction as the physiological issue that it is. No, Sandra’s society had little patience with people living with addiction. There was little understanding of the trauma that often leads to substance abuse issues or the ways that addiction impairs our freedom, making many who are dependent on drugs all but incapable of stopping without help. Still, Sandra saw the dignity of those she served.

She lived a life of radical mercy and deep meaning, all because she never tried to distinguish between the “deserving” and the “undeserving” poor. She just poured out the mercy of Jesus on anyone she could find.

By this time, she was a medical student with a fiancé, a popular young woman with the world at her feet. But despite her full life (and her busy schedule), Sandra couldn’t look away from the suffering she saw in the rehab center where she worked. She wouldn’t turn from these people, even when they raged at her, ignored her or ridiculed her. She refused to dismiss them as being unworthy of her love because she was driven by the love of Jesus, who holds nothing back. But this was no condescending act of charity; Sandra was grateful for the friendships she built, speaking of each man by name and pointing out the sweetness of one, the simplicity of another, and the need to listen and understand that drove a third. It was her smile and her eagerness to listen that helped the patients to open up. One man later wrote of her contagious joy, which enabled him to work toward recovery; he has now been sober for 40 years, a fact he attributes to Sandra.

Many of us would hear of work like Sandra’s and suggest that she take a break while finishing medical school and planning her wedding. But it’s a good thing she didn’t. Had she waited to serve until a more opportune time in her life, she never would have begun to serve at all. Sandra was killed in a car accident at only 22. She was never able to finish medical school, never married her fiancé. But she lived a life of radical mercy and deep meaning, all because she never tried to distinguish between the “deserving” and the “undeserving” poor. She just poured out the mercy of Jesus on anyone she could find.

________

As we read these stories of dramatic moments and impressive ministries, it’s easy to admire these saints from afar and excuse ourselves from any similar call. But if there’s one thing we can learn from St. Faustina, it’s that sharing the mercy of God is worth any cost. This Divine Mercy Sunday, take some time to ask the Lord: What person or people do I least want to extend mercy to? And how exactly can I start?