Nearly 30 years ago, six women — three pro-life leaders and three pro-choice leaders — began meeting in secret in a windowless basement. In the aftermath of recent abortion clinic shootings, they quietly gathered to discuss the issue of abortion and how to prevent future violence.

By the time they shared their secret with the world, they not only respected one another but also called each other friends.

“In this world of polarizing conflicts, we have glimpsed a new possibility,” they later wrote in The Boston Globe, “a way in which people can disagree frankly and passionately, become clearer in heart and mind about their activism, and, at the same time, contribute to a more civil and compassionate society.”

Today, their story is the focus of a new docuseries called “The Basement Talks” available through Prime Video, Apple TV and Google Play from production company Matters Media. The six episodes follow the fatal shootings at two abortion clinics in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1994 by a man named John Salvi and how they prompted six local leaders on opposing sides of the abortion debate to meet and develop lifelong friendships.

Two of the women, Melissa Kogut, former executive director of NARAL Pro-Choice Massachusetts, and Frances X. Hogan, a legal professional who has served in leadership roles for several pro-life and Catholic organizations, including Women Affirming Life and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ (USCCB) Committee on Pro-Life Activities, spoke about the experience with Our Sunday Visitor.

The pro-life women, Hogan said, were initially concerned about causing a scandal if people found out about the meetings. She later realized the meetings presented an opportunity.

“It’s actually a way to model behavior in terms of treating everyone with dignity and respect, even those people with whom you profoundly disagree,” she said.

While the Catholic Church teaches that human life must be respected and protected from the moment of conception, Hogan emphasized that Pope Francis himself has encouraged people who disagree to enter into dialogue.

The conversations

Their dialogue was organized by the Public Conversations Project, known today as Essential Partners (EP), a nonprofit dedicated to helping people “build relationships across differences to address their communities’ most pressing challenges.” Together with mediator Susan Podziba, EP co-founder Laura Chasin designed and facilitated the conversations.

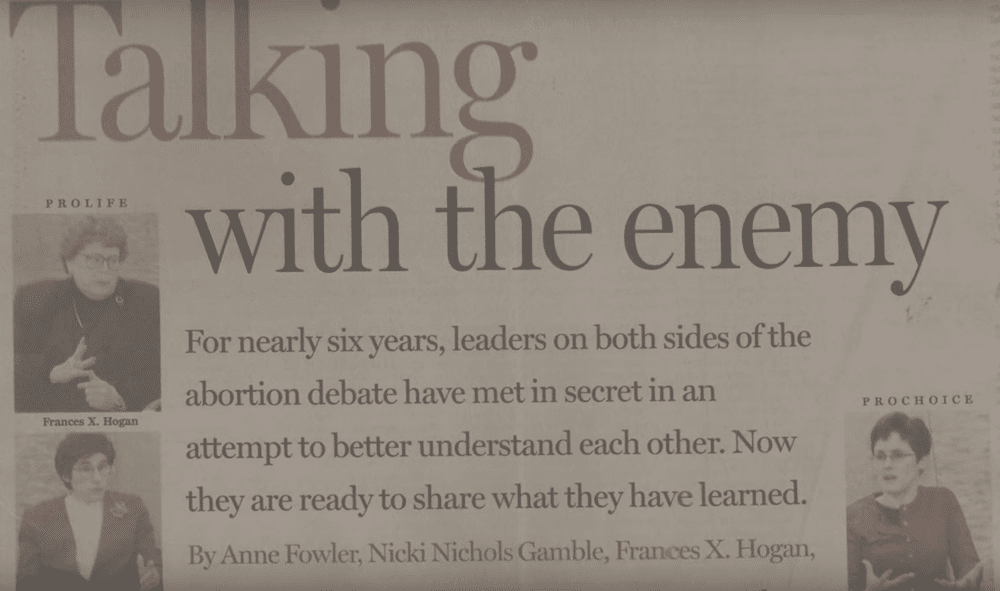

In 2001, after nearly six years of meeting in secret, these women shared what they learned publicly in a piece published by The Boston Globe called “Talking with the Enemy.”

The docuseries came into being more than 20 years later after husband-and-wife team Josh Sabey and Sarah Perkins, the co-directors of the series, who identify as Mormon, accidentally came across 150 hours of the conversations on cassette tapes in a storage unit.

“They shared a lot of personal stories,” Sabey told Our Sunday Visitor. “They actually kept the audio rolling during meals. There was a lot of laughter, they laughed and joked. They’re funny, charismatic people.”

Perkins added: “The dialogue that you hear happening on the tapes is much slower and more measured and careful and thoughtful than dialogues that you typically hear on controversial issues, in person or in the news.”

In addition to Hogan and Kogut, the docuseries features the other four women involved: Rev. Anne Fowler, an Episcopal priest and pro-choice advocate; Madeline McComish, former president of Massachusetts Citizens for Life; Nicki Nichols Gamble, former president of Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts; and Barbara Thorp, former director of the Archdiocese of Boston’s Pro-Life Office, who has served on the boards of several pro-life groups.

The importance of language

The six leaders originally agreed to four meetings. One of the first things they discussed was how to speak with one another — and which words to use or avoid.

“We all were using certain terms to talk to our own base of supporters for the purpose of mobilizing them,” Kogut said. “That’s not the same thing as having a nuanced conversation with people, and you want to be respectful of them in order to have a relationship — and we had to learn how to do that, to be able to listen to one another.”

Words like “fetus,” Kogut said, triggered the pro-life leaders, while words like “baby killer” triggered the pro-choice leaders.

“We agreed to which terms we would use for the purposes strictly of talking to one another and being able to listen,” she said. “A lot of trust was built in those early days.”

The six women learned to compromise. One of the lessons she learned, Hogan said, was to call people what they wanted to be called even if she disagreed with it. They decided on “pro-life” and “pro-choice.”

“We wouldn’t agree with ‘pro-choice’ for the title of our opponents,” she remembered. “But let’s get past those labels, and let’s move on to the substance of what we’re discussing and the content of it.”

While the pro-life women wanted to use the term “unborn child” and the pro-choice women wanted to say “fetus,” they finally agreed upon “human fetus” — which none of them liked, Hogan said.

She said that there were hundreds of terms that they couldn’t use when speaking with one another.

“At one point, I wasn’t sure we were even going to be able to talk because all the terms were being taken away from us,” she said. “But it made you dig deeply for words that you could have a conversation about.”

The importance of listening

After the four meetings, the six women agreed to continue. Their lives, they said, changed.

“I was surprised how interesting [the meetings] were because I thought I knew everything I needed to know already based on the news,” Kogut remembered.

Hogan also learned something new.

“They taught us how to listen to what the other person was saying, and not just be preparing your answers and your arguments, but to really listen,” Hogan said. “It was very often that we found out they weren’t saying what we thought they were saying.”

“I think in my life and in my activism,” she added, “that’s helped me to listen to what the person is saying and actually respond to that, and not to what you think they’re saying.”

Respect for the ‘other side’

Hogan and Kogut shared how people who feel strongly about abortion should think about those they disagree with — or how pro-lifers should think about pro-choicers and how pro-choicers should think about pro-lifers.

“I feel very strongly that we should have respect for every human being on the face of the earth, no matter what their position [is] on any issue,” Hogan said, “and they deserve the same respect as what I would say about the unborn child.”

“Do I respect the positions they take? No,” she added. “Do I respect that human person? Absolutely.”

Hogan identified one of their achievements as the chance to say, “I don’t agree with you, but I respect you and I want to know why you believe what you believe.'”

Adding to that, Kogut said one of the most important things she learned was how to be curious.

“When you’re in the middle of a political, polarized situation, there’s not a lot of curiosity about your opponents,” she said. “It’s, ‘Okay, how do we win this — how do we win this legislative battle? How do we get the points in the news?'”

The aftermath of ‘Roe v. Wade’

Hogan and Kogut called civil discourse between people who disagree about abortion more important than ever, two years after the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision that previously legalized abortion nationwide.

“Now we’re in battles in all 50 states basically, because it’s coming back to the states,” Hogan said of the issue of abortion. “I think that the civil discourse is so important now especially. “

Kogut also saw a need.

“It’s hard to have a civil conversation when there’s so much at stake,” she said. “But I think in general there needs to be a commitment across the board, not just around abortion, for a civil society, which we’re not at all experiencing right now.”

A central message

Both Hogan and Kogut hoped that the new docuseries would impact viewers. For her part, Hogan wanted people to walk away with the idea of engaging in civil dialogue as well as the need to continue the conversation on the substance of the abortion issue. Kogut wanted the series to leave people inspired.

“Inspired to see that one of the most polarized issues ever, the abortion debate, we were able to spend this time together to learn about one another and how meaningful that was,” she said. “If more people did that, that would be amazing.”

They agreed that dialogue is a way to move forward even as people continue to disagree.

“That’s one of the things that I learned is the beliefs on both sides, the values are so strong,” Kogut said. “I think all that we can hope for is that, as we as a society figure out how we’re going to operate regarding this issue, that we do it civilly and respectfully.”