It was so hot and the air conditioning was so feeble I almost bailed out of line at the Salvation Army. Instead, I passed the time by checking out the jewelry case.

Blue rhinestone earrings. Some plastic bracelets. A grimy jackknife. And two relics.

Yes, relics. They were unmistakable to the Catholic eye. Two round, brass cases the size of a half dollar, each with a glass window showing a scrap of organic material mounted on red cloth with a tiny paper label underneath. I didn’t have my reading glasses, so I couldn’t see who they were. But they were clearly somebody.

They were $3 each, so I bought them, tucked them into my wallet and drove home — trembling.

At home, I took a closer look, and nearly fell down. One said “s.Helen.Imp” and the other “S. Petri Ap.” St. Helen? St. Peter? Was this possible?

I opened the backs, and each one revealed a blob of red wax imprinted with a seal holding in place two thin red cords. These were starting to look very real indeed.

I took careful photos and sent them to Sacra, a Minneapolis-based private organization that restores and documents relics. Then I went back to the store to tell the manager it’s not her fault she didn’t recognize these things as relics, but if she gets any more, she should call a priest; these were very likely human remains.

Strange that they ended up at a Salvation Army in rural New Hampshire; but perhaps stranger that the Catholic Church is in the habit of saving little bits of bodies and bones and scraps of hair and cloth, putting them under glass, and praying before them in our homes and in our churches.

Why do we do this? What does it mean?

Pagan dread

Catholics have collected and preserved relics of their holy dead since the earliest days of the Church.

“Anywhere you have the authentic Catholic faith, you have relics,” Sean Pilcher, founder of Sacra, told me.

When Emperor Trajan threw St. Ignatius of Antioch to the lions around the year 110, Christians recovered what was left of his body, and now his arm, breastbone and possibly his head repose in various churches. When St. Cyprian was beheaded in 259, Christians spread cloths to sop up his spilled blood.

St. Polycarp, a disciple of the apostle John, was martyred by burning in the year 155, and the faithful collected his ashes and venerated them, calling them “more valuable than gold,” according to Deacon Tom McDonald, a teacher, hospital minister and author of the Weird Catholic Substack.

What Christians were doing was something new, and their pagan neighbors were baffled and sometimes horrified to see them so comfortable with death. It’s one thing to have keepsakes of the beloved dead, but it’s another to keep pieces of the dead themselves. The Jewish people considered dead bodies ritually impure, and even cultures that worshipped their ancestors generally did so with more fear than reverence.

“The dead are protected against, chained down, covered in amulets to keep them from walking,” McDonald told me. “(Stories about) ghosts in the ancient world almost uniformly are based on failure to properly care for the body.”

But Christians were not only unafraid of the dead, they believed the remains of the dead were a connection to eternal life.

“Relics are inherently sacred things. If you say St. Andrew is in heaven, what you really mean is the soul of St. Andrew is experiencing the beatific vision; but his body is really him. It’s still on earth. So there is some way that Andrew, who is beholding the face of God, is still connected to his body,” Pilcher said.

The bodies of the saints — especially the martyrs, who willingly followed Christ in death — have a particular relation to the the risen body of Christ.

“We believe those remains will participate in the resurrection, and we anticipate that moment by preserving them and venerating them,” McDonald said.

“We don’t kick someone out just because they’re dead. They’re still going to come to Mass. We’re going to put them close to the altar, because that’s the first place the dead will rise. We won’t be afraid of them anymore. In fact we’re going to put their heads in glass cases and process them around the church. Take that, pagans!”

Modern squeamishness

If ancient people were afraid of making contact with dead bodies, modern people — even Catholics — often find it distasteful or disgusting. This unease is partly because modern people simply aren’t used to being close to death. We hide dead bodies away, and if they’re on view at funerals, they’re embalmed and heavily made up.

But even those who are comfortable with death might ask how Catholics can claim to respect the human body so highly, from conception to natural death, and then cut the best ones up into bits and send them around the world.

The simple answer is: If we believe something is holy, it’s natural to want to share it.

“We want to spread that holiness around as much as possible,” McDonald said.

The collection of relics is a respectful, almost liturgical process, and is done with great reverence, Pilcher said. Catholics really do care about bodies, because we believe God cares.

“It’s the basic idea that matter matters. We’re sacramental people. Matter is created by God; it’s the way he conveys grace,” said McDonald. This includes not only parts of their bodies, which are called first-class relics, but things holy people owned. These are second-class relics.

The ancient Jews certainly collected these. The Ark of the Covenant, said Pilcher, is nothing if not a reliquary; it contained Aaron’s staff, the tablets of the Ten Commandments, and some manna. These relics were so sacred that when Uzzah, who was not a member of the priestly tribe, impiously touched the Ark, he was instantly killed (2 Sm 6:6-8).

The practice of collecting and reverencing second-class relics continues into the New Testament. In Acts, the faithful touched handkerchiefs to St. Paul and brought them to the sick, who were healed (19:12). The woman with the hemorrhage reached out and touched Jesus’ cloak, and she was healed (Mt 9:19-21). People would even lay the sick on mats where St. Peter was passing by, in hopes that his shadow would touch them and heal them (Acts 5:15).

“God doesn’t need physical things, but he chooses to work through them,” Pilcher said. “We’re an incarnational faith. Relics are the crossover between the communion of the saints and the Incarnation.”

Relic collection began in the early days of the Church, but it picked up speed in the fifth century, when a shrine was built over the tomb of Martin of Tours. It also housed half his cloak, which he famously shared with a beggar who was revealed in a dream to be Christ himself.

The miraculous healing pilgrims received led to a great flowering of devotion to saints that spread through the western world — and, importantly, there was copious documentation of the miracles that occurred. So many people recorded evidence of the real effects of praying to a saint. Historians point to this era as vital to the development of the cult of saints, namely, the practice of praying to a particular saint for intercession and building churches in their honor. In fact, the word “chapel” is derived from “cappella,” or “little cloak.” This etymological tidbit points to a broader connection: Churches for worshipping God are built literally on top of the relics of saints. That’s how central relics are to the Church, and that’s how powerful they can be.

St. Thomas Aquinas went so far as to call relics “organs of the Holy Spirit” — instruments through which God works. But he also worried the faithful could go off the rails, falling into idolatry.

Catholic exuberance

By the late Middle Ages, that had certainly come to pass. The unrestricted commercialization, forgery, and general blinging-out of relics was widespread and unrestrained. Martin Luther, for all his errors, wasn’t wrong when he sneered that Catholics would pay good money to see “a feather from Gabriel’s wing.”

The trade in fake relics was so prevalent that the Pardoner in Chaucer’s fictional “Canterbury Tales” boasts he only needs some Latin-sounding words and official-looking documents to make a tidy profit off a holy mitten whose wearer “shal have multipliyng of his greyn.”

So the Church cracked down. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 said current practices were inflicting “great injury” on the Faith, and that relics must be authenticated and documented and not displayed for money. The third session of the Council of Trent in the mid-1500s repeated these points and decreed that bishops must authorize any relic’s display, the family of the dead must consent before bodies are dismembered, and any relic that couldn’t be authenticated should be discarded. They wanted to avoid “all lasciviousness” and any taint of “filthy lucre.”

Did Catholics listen?

In 1578, Roman workers uncovered the “Catacomb Saints,” a trove of skeletons believed to be of early martyrs. European Catholics whose shrines had been despoiled by the Reformation eagerly collected the bones, reassembled them, bedazzled them with the most extravagant gems and posed them dramatically in wigs and brocades, reclining, gesturing beneficently, or in one case even proffering a glass vial of (according to rumor) his own blood.

But although these displays look ludicrously excessive to modern eyes, they didn’t contradict Church teaching, Pilcher told me.

“You can have some crazy baroque place in Austria with a saint all glitzed up in crowns and tiaras, but that’s not really that different from a statue of Mary wearing a crown. In fact, a relic is probably better, because it’s an inherently sacred thing.”

Fashions and cultural sensibilities within the Church fluctuate, but relics themselves have always been central. Even when the aesthetics surrounding them are at their most lavish, they always point to the Incarnation.

“The Catholic faith does not hinge on the authenticity of this or that relic, but they’re not really a peripheral teaching. They’re not optional; they’re biblical,” Pilcher said.

And they are more powerful than we might realize.

“If we had supernatural grace goggles, we’d be kind of spooked by them. St. John of Damascus calls them ‘fountains of salvation,'” Pilcher said.

There will always be careless or malicious actors, but the Universal Church has a real interest in keeping her sons and daughters from idolatry, he said.

Scientific rigor

The Church does not require us to blindly accept that relics are what we say they are. In fact, authentication is objective and rigorous.

“It’s like studying any other historical artifact,” Pilcher said.

He heads a small staff of experts in heraldry, Latin, Church history, art history, archival skills and paleography. When they receive a relic, they first examine its physical accidents.

“I have a microscope, and that solves a good number of problems for me,” Pilcher said.

But chemical tests like carbon dating are less helpful than people may imagine. They might, for instance, verify that a bone is from a first-century Palestinian, but they can’t prove that it’s some specific person; and the process might damage the relic. Pilcher said the best clues are often found through research.

“It’s a question of tracing a line of provenance between wherever the saint died or where his body is, to the thing I have in front of me,” he said. “A lot of that is based on who prepared the relic.”

The Church moves slowly and ponderously, and a relic from a millennium ago may only have changed hands once or twice, leaving a clearly documented trail. Officially moving a relic is called “translating” it, and it doesn’t happen without a fuss; almost nothing happens without someone writing it down.

“We’re the longest existing institution in the whole world. We have stuff on record from forever ago,” Pilcher said.

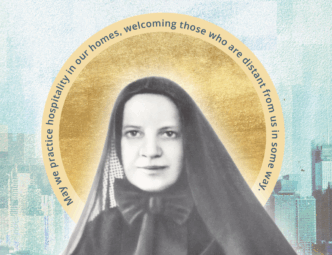

Pilcher’s team determined that one relic I sent them was indeed Saint Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine and traditionally recognized as the finder of the true cross. And it is a first-class relic, a fragment of her bone.

But the one of St. Peter is a bit of wood from his altar. Not the altar at the Basilica in Rome, but the altar on which St. Peter the Apostle said Mass. It is a second-class relic, and a monumental one.

“The entire Catholic claim stands upon apostolic succession from St. Peter, so the fact that we have that altar, and people can venerate it, might make it one of the more Catholic relics around,” Pilcher said.

“It lays to rest the idea that Jesus didn’t really need to found the Church. Peter was a bishop, and this is where he said Mass,” he said.

Catholics often speak of “third class relics” — something that has been touched to a first-class relic. But these strict classifications, while a helpful shorthand, can be misleading.

“The Church doesn’t really use those terms,” Pilcher said.

What some call a “third-class relic” is really more of a devotional practice.

“It’s like making a pilgrimage. You’re mindfully and deliberately entering into a relationship with that saint; your praying or touching an object is your encounter,” he said. It’s praiseworthy, but it doesn’t make sense to say such an encounter is somehow rated lower than a second or first-class relic. It’s just a different kind of thing.

This mindful spiritual relationship can keep us from treating relics superstitiously.

“A faithless or non-religious person couldn’t steal a relic and heal somebody. It’s not a talisman,” Pilcher said. “For believers — in a state of grace, especially — it’s a channel God can use to convey his grace and physical or spiritual healing.”

When the woman with the hemorrhage catches up with Jesus and touches his cloak, he says, “Take heart, daughter; your faith has made you well” (Mt 9:22). And even the hypocritical Pardoner from Canterbury Tales warns potential customers that if they “hath doon synne horrible,” they will “have no poer ne no grace” from his “relics.”

There are, as often happens with God, some dramatic exceptions to what we perceive as “rules.” In 2 Kings 13, a group of Israelites is attempting to bury a man, but they’re surprised by raiders, so they quickly toss the body into a handy grave — which happens to belong to the prophet Elisha. The dead man instantly springs up, alive again. 4th-century theologian Ephrem the Syrian says that “the power the Lord gives to the bones of Elisha is the symbol and seed of resurrection.”

Even before Jesus was born, relics pointed to the Resurrection.

Divine providence

A few friends nervously warned me I was violating canon law by buying the two relics for $6, but this isn’t accurate. I wasn’t trying to profit off them; I was only trying to keep them from being profaned. I learned it’s sadly common for relics to turn up in places like the Salvation Army. As the world becomes more secular, and convents and churches close, countless relics have been ignorantly donated or put up for auction, “alienated” from their proper context, Pilcher said.

Nevertheless, he discourages the faithful from going on personal crusades to rescue relics from eBay. That just encourages scammers to produce more fakes.

“Relics of the saints have a way of finding where they need to go,” he said.

Why did they find their way to me? I can’t say for sure, but they were marked with the episcopal seal of Bishop Giuseppe Placido Nicolini, who founded The Assisi Network, which saved more than 300 Jews from the Nazis and even helped them preserve their own religious practice. My own family may have been part of that 300.

If a layperson does find a real relic, he’s not obligated to turn it over to the Church unless it’s something major like an arm (and most relics in the United States are fragments, not entire limbs). But it should be treated with dignity and kept somewhere designated for prayer, like a home altar or prayer corner. It’s good practice to light a candle when it’s on display and to bow to it.

“We should be aware of the presence of the saint,” he said. “It shouldn’t just be out and about, hanging out.”

That’s why I felt uneasy keeping my relics in our house. It was too easy to forget they were there, and I didn’t want them to be forgotten.

So I asked my pastor, Father Alan Tremblay, if I could entrust them to the parish. He enthusiastically agreed, and then told me a little story. Not long ago, he was in his chapel thinking about how other parishes have relics they’ve cherished for generations.

“I was kind of lamenting we didn’t have that, and I prayed, ‘Lord, I would love to have some relics, if you want to send some our way,'” he said.

He got 18.

Within weeks, he received a tremendous bequest from a parishioner who left 16 relics to the parish: First-class relics of Sts. Bridget, Bernadette, Peregrine, Anthony, Maria Goretti, Mary Magdalen, Monica, Augustine and Cecilia; a second class relic of Therese of Lisieux; and, incredibly, first class relics of six of the apostles: Phillip, Thomas, James, Bartholomew, Andrew and John.

“It’s hard not to see it as providence,” Father Tremblay said.

All 18, including the relics of St. Peter and St. Helen, are now displayed together in two reliquaries on the high altar of St. Bernard Church in Keene, New Hampshire, and Fr. Tremblay has been gratified at the parish’s response.

“We didn’t need a relic,” he said; but there is something about the tangible presence of the saints that fosters reverence.

The school kids, in particular, are impressed by relics.

“The children were deeply moved. Catholic or not, they wanted to learn more and were kind of awed,” he said.

Father Tremblay said, as a pastor, he tends to be overcautious, worrying people will fall into superstition. But sometimes caution can be a hindrance to devotion.

“We have to open our hearts up to the reality: This is real. There’s grace in devotion to the saints,” he said. “The saints are the church. And every now and then, they kind of show up,” Father Tremblay said.

The wave of fanciful miracles associated with relics in the Middle Ages has receded, but miracles still do occur. St. Carlo Acutis, who was canonized in September, healed a dying Brazilian boy who kissed a piece of Acutis’ clothing and prayed for healing.

McDonald said that God uses relics to tell us, “Yes, the resurrection is real, and I’m gonna give you a little taste of its power.”

Sometimes a relic is an obvious conduit of grace; sometimes it isn’t so obvious. Sometimes it takes a while.

You’ve got to give relics “time to breathe,” McDonald said. They have a tendency to resurface when they have some particular grace to impart.

He compares the phenomenon to a painting which, up close, looks like nothing but a field of black and white dots. But when you back away and give it some space, an image emerges.

“It might be one hundred years down the road, or when we’re standing in front of the throne of majesty” before we understand what a relic is meant to do, he said. In the meantime, it works on us in ways we don’t understand.

“And that’s okay,” he said. “I like to leave a little space for mystery.”

Correction: In an earlier version of this article, Deacon Tom McDonald was incorrectly identified as a “hospice minister.” He is a hospital minister.