During an adult religious education session, the instructor was discussing the Immaculate Conception and said that the Blessed Mother was conceived without original sin, born without sin and lived without sin. One of those listening immediately responded: “Oh no, you got that wrong! The only person to live a sinless life was Jesus.”

Even after nearly 2,000 years, we still have trouble fully appreciating the beautiful Church teaching about the conception of Mary.

Not only are some of the faithful confused about the Mother of God being conceived, born and living without sin, but some think the Immaculate Conception refers to Jesus. Even certain Church Fathers and theologians had questions regarding Mary’s conception.

Today, many — especially outside the Church — seek to find flaws with this doctrine that evolved to become a belief by all Catholics. It took centuries of discussion, debate and devotion to the Blessed Mother and a groundswell from the laity and the clergy before the Church magisterium confirmed a dogma — an article of faith — to be believed by all the faithful, that Mary was immaculately conceived.

Church dogma is a truth revealed by God, declared as such by the infallible authority of the magisterium and considered necessary for salvation; the terms “official Church teaching” and “articles of faith” are sometimes used in a synonymous way.

Early beliefs about Jesus and Mary

The basic Christian beliefs regarding the divinity of Jesus and holiness of Mary were not widespread issues among the early followers of Christ, at least not until Constantine eliminated religious persecutions in the fourth century; suddenly, Christians began to publicly debate different aspects of Christian teaching.

Early on, the Arians contended that Jesus and God were not the same; a priest named Arius promoted this heretical belief, claiming Jesus was a great prophet and teacher but he was not God. It took the first ever Church-wide (ecumenical) council in 325, at Nicea, Turkey, to sort this issue. The Church bishops assembled and proclaimed that Jesus and God were equals, and then put a sharp point on the matter by issuing a creed that echoed their sentiment that Jesus is “consubstantial with the Father.” Arius was excommunicated, but the issue did not fully go away.

During the next century, Nestorius, the bishop of Constantinople, took another approach to reject the divinity of Jesus. He preached that Mary was the mother of Jesus but not the mother of God, meaning that Jesus and God were not the same. He had many supporters, and again, the Church bishops congregated (the Third Ecumenical Council), this time in the town of Ephesus, Turkey, in the summer of 431.

| An Act of Consecration |

|---|

|

The following is a portion of the decree used by the bishops of the United States at the First Council of Baltimore in 1846 to consecrate the country to Mary under her title of the Immaculate Conception. “Most Holy Trinity, Our Father in Heaven, who chose Mary as the fairest of your daughters; Holy Spirit, who chose Mary as your spouse; God the Son, who chose Mary as your Mother; in union with Mary, we adore your majesty and acknowledge your supreme, eternal dominion and authority. “Most Holy Trinity, we put the United States of America into the hands of Mary Immaculate in order that she may present the country to you. Through her we wish to thank you for the great resources of this land and for the freedom which has been its heritage. Through the intercession of Mary, have mercy on the Catholic Church in America. Grant us peace. Have mercy on our President and on all the officers of our government. Grant us a fruitful economy born of justice and charity. Have mercy on capital and industry and labor. Protect the family life of the nation. Guard the precious gift of many religious vocations. Through the intercession of our mother, have mercy on the sick, the poor, the tempted, sinners — on all who are in need. … “Protect us from all harm. O sorrowful and immaculate heart of Mary, you who bore the sufferings of your son in the depths of your heart, be our advocate. Pray for us, that acting always according to your will and the will of your divine son, we may live and die pleasing to God. Amen.” |

St. Cyril, bishop of Alexandria, opposed the false teaching of Nestorius and had written the misguided bishop several letters telling Nestorius he was preaching heresy. At the council, the bishops affirmed the decisions of Nicaea, that Jesus was consubstantial with the Father, and defined Mary as the Mother of God. While the doctrine of Mary’s Immaculate Conception was not addressed at either of these councils, the bishops had announced to the world that Jesus was divine and Mary was his mother. That she was somehow tainted with sin was not questioned until 300 years later when a celebration of the Conception of Mary began in the Church. As early as 388, St. Ambrose wrote, “Mary, a virgin not only undefiled but a virgin whom grace has made inviolate, free from every stain of sin.”

By the eighth century, the Eastern Church was celebrating what it called the feast of the Conception of Mary by St. Anne, and over the next 100 years, it spread to the West, first to Southern Italy, then Ireland, and by the 11th century to France and other European countries. As the feast broadened in Europe, the emphasis of the devotion changed from St. Anne to an emphasis on Mary and that she was conceived without sin.

It was in France that St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) raised objection to the belief about a sinless conception. He said: “I say that the virgin Mary could not be sanctified before her conception, inasmuch as she did not exist. If, all the more, she could not be sanctified in the moment of her conception by reason of the sin which is inseparable from conception, then it remains to believe that she was sanctified after she was conceived in the womb of her mother. This sanctification, if it annihilates sin, makes holy her birth, but not her conception. No one is given the right to be conceived in sanctity: only the Lord Christ was conceived of the Holy Spirit and he alone is holy from his very conception” (Letter to the Canons of Lyons).

Any of the theologians of that era who opposed Mary being conceived immaculately without original sin argued along these same lines, including, St. Albert the Great (1206-80) and St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-74). They pointed to the fact that original sin is inherent, universal to every man, save Jesus, and referred to Romans 5:12: “Therefore, just as through one person [Adam] sin entered the world, and through sin, death, and thus death came to all, inasmuch as all sinned.” Accordingly, all men needed the redemption given by Jesus Christ — all needed a savior.

How, then, could Mary have been free from original sin, if Jesus had not yet been born, had not yet died on the cross and resurrected? They could accept that she was cleansed from original sin sometime between conception and birth, which was the case with John the Baptist, but they couldn’t accept her being conceived with no sin.

An explanation by Blessed Duns Scotus

The complex issue was explained by the Blessed Duns Scotus, a Franciscan who lived from 1266 until 1308. He reasoned that because Mary was going to be the vessel that carried Jesus for nine months and was the source of the miraculous birth, that she could never be soiled with original sin or any sin. She was preserved from all sin at the moment of conception in her mother’s womb, redeemed in advance — a preserved redemption. At her conception, she was infused with supernatural grace in the manner of Eve; she was conceived without sin, born without sin, and, unlike Eve, lived without sin. While original sin is removed from us at baptism, she, because she was destined to become the Mother of God, was, in a unique and singular way, never allowed to acquire sin.

Duns Scotus used this example: “It is a more excellent gift to preserve someone from evil than to permit them to fall into evil and afterwards to deliver him from evil. Thus it is for Mary a more excellent gift to be preserved from original sin than to permit in her the contraction of original sin, and to purify her from it.” While this rationale was accepted by many, the Church did not define the Immaculate Conception as dogma or as an article of faith for another 500 years.

Middle Ages belief

In the 14th century, the feast was called the Feast of the Blessed Virgin’s Conception and added to the universal Church calendar, but Catholics were not required to accept it as official Church teaching. Then, as now, the thinking was not that Mary was conceived or born miraculously like Jesus; indeed, she was conceived by relations between her parents, born like every other human being. But unlike others, the sin of Adam was never transferred to her. At the moment, in her Mother’s womb, when her soul was united with flesh, she was infused with supernatural grace and protected from original sin.

It appeared that a major advancement in the Church — wide proclamation of this belief — was fermented at the Council of Basel (1431-49). The bishops made it clear that Mary, “through the workings of a singular preventive grace was never subject to original sin and always immune from original and actual sin.” The bishops went on to say that this belief had been long held in the Church: “We define that it is to be approved by all Catholics and that from now on no one should be allowed to preach or teach the contrary.” This seemed to move the belief forward toward an official proclamation, but unfortunately, at that time in history, the bishops were not in communion with the pope, and the decrees of the council were not binding.

Nearly 50 years later, Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-84) approved the feast of the Conception of the Immaculate Virgin Mary in the Diocese of Rome and encouraged all Christians to celebrate the feast and believe in the Immaculate Conception. Sixtus also directed that those celebrating the feast or believing in the Immaculate Conception would not be rebuffed by anyone in the Church.

At the Council of Trent, (1545-63) the bishops avoided discussion of original sin as it applied to Mary but referred to the guidance of Pope Sixtus IV: “The constitutions of Pope Sixtus IV of blessed memory are to be observed …” (fifth session, 1546). In 1661, Pope Alexander VII (r.1655-67) declared in a papal bull, Sollicitudo omnium Ecclesiarum, that Mary was conceived without original sin and that the feast of the conception celebrates that fact. This bull would have an impact on the eventual decision to declare the Immaculate Conception a Church dogma. Pope Clement XI (r. 1700-21) extended the feast of the Conception to the universal Church.

Increased devotion

Devotion to the Immaculate Conception continued to increase among the laity and clergy as the 19th century began. In 1830, the Blessed Mother appeared in several visions to a nun named Catherine Labouré — later named a saint — at the Daughters of Charity monastery in Chatillion-sur-Seine, France. On Nov. 27, Catherine saw Mary appearing as a picture inside an oval frame standing on a globe with light streaming from her hands. The vision included an inscription: “O’Mary conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee.” Our Lady asked Catherine to pursue the making of a medal based on the vision that Catherine was witnessing. This medal was initially called the Immaculate Conception Medal, but so many miracles came to those who wore it that it became known as the Miraculous Medal.

Between 1834 and 1847, the Holy See reportedly received 300 petitions seeking permission to insert the word “immaculate” into the Preface of the Mass on the feast day of Our Lady of the Conception. The people of the United States were devoted to the Immaculate Conception, and in 1846 the bishops of this country chose the Blessed Virgin Conceived without Original Sin as the patroness of the United States. They requested and received permission from the Vatican to add “immaculate” before the word conception in the Office of the Conception of the Blessed Mother and in the preface of the feast day Mass. All this widespread devotion, as well as that of Christians for centuries, took place before the Church defined the Immaculate Conception as dogma to be believed by every Catholic.

Declaring the dogma

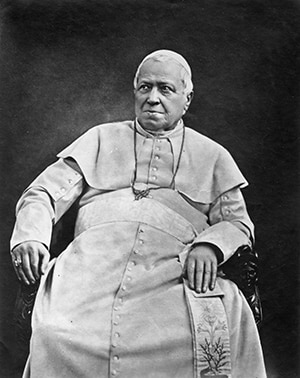

Pope Pius IX (r. 1846-78), witnessing the continuous Church-wide love and affection for the Blessed Mother as the Immaculate Conception, issued a letter to the worldwide bishops requesting their feedback, that of their clergy and the laity, as to whether or not this long held belief should be adopted as a Church dogma. Pius also convened a group of theologians to study the history and Church documents to determine if the belief could be dogmatically defined. The responses were overwhelmingly positive. People throughout the world prayed that the pope would approve and adopt this belief as universal throughout the Church.

| ‘Ineffabilis Deus’ and declaring a dogma |

|---|

|

|

On Dec. 8, 1854, in the presence of 40,000 people including hundreds of bishops and cardinals, Pope Pius, with great emotion, read his degree, Ineffabilis Deus (“Ineffable God”), in which he eloquently pronounced the Blessed Mother “preserved from all stain of original sin,” that she was immaculately conceived (see sidebar). Catholics rejoiced at this infallible act by the Holy Father, an act that affirmed what had been believed by Christians from antiquity, promoted and avowed by popes, Church councils and especially the faithful whose love for the Blessed Mother has continued and grown through the centuries. This papal letter elevated Mary’s perfection to new heights throughout the world, defining that the Mother of God was perfect — is perfect in every way even from her conception.

Just four years after Pope Pius IX’s papal bull, God affirmed this dogma at Lourdes, France, where a young woman, Bernadette Soubirous, experienced a series of visions of Our Lady. On March 25, 1858, Bernadette asked the Lady her name, and the Blessed Virgin responded, “I am the Immaculate Conception.” The 14-year-old Bernadette, as well as her parents, had allegedly never heard that name before. The Church has authenticated this Marian apparition; Bernadette was declared a saint in 1933, and Catholics annually celebrate the memorial of Our Lady of Lourdes on Feb. 11.

Every Advent, as we await the birth of Our Savior, the holy season is punctuated by the solemnity of the Immaculate Conception. On Dec. 8, we are called to this beautiful holy day of obligation, to celebrate once again the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Mother and how God almighty prepared her for her role in salvation history, her role as the Mother of the Messiah. The Mass collect on that day reads: “O God, who by the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin prepared a worthy dwelling for your Son, grant we pray, that as you preserved her from every stain of sin by virtue of the death of your Son, which you foresaw, so, through her intercession, we, too, may be cleansed and admitted to your presence.” Amen.

D. D. Emmons writes from Pennsylvania.

| A Prayer to the Immaculate Conception |

|---|

|

O Mary Immaculate, — Given by Pope Francis on Dec. 8, 2019 |

The words at the heart of this beautiful papal bull of Pope Pius IX and those most often repeated are found in that part of the document titled “The Definition”: “Accordingly, by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, for the honor of the Holy and individual Trinity, for the glory and adornment of the Virgin Mother, for the exaltation of the Catholic faith, and for the furtherance of the Catholic religion, by the authority of Jesus Christ, Our Lord, of the blessed apostles Peter and Paul and by our own: We pronounce and define that the doctrine which holds that the Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first moment of her conception, by a singular privilege and grace of Almighty God, in view of the merits of Christ Jesus, Our Savior, was preserved immaculate from all stain of original sin, is revealed by God and therefore is to be firmly and confidently believed by all the faithful.”

The words at the heart of this beautiful papal bull of Pope Pius IX and those most often repeated are found in that part of the document titled “The Definition”: “Accordingly, by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, for the honor of the Holy and individual Trinity, for the glory and adornment of the Virgin Mother, for the exaltation of the Catholic faith, and for the furtherance of the Catholic religion, by the authority of Jesus Christ, Our Lord, of the blessed apostles Peter and Paul and by our own: We pronounce and define that the doctrine which holds that the Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first moment of her conception, by a singular privilege and grace of Almighty God, in view of the merits of Christ Jesus, Our Savior, was preserved immaculate from all stain of original sin, is revealed by God and therefore is to be firmly and confidently believed by all the faithful.”