Those who know me well know of my love for the magnificent land that is our 50th state, Hawaii. I have developed a true Hawaiian “ohana,” a family, on my 10 trips to this paradise, and we all have two things in common: our love for Hawaii’s two saints, St. Damien and St. Marianne Cope, and our hope for a possible third saint.

On my first two trips to Hawaii in 2008 and 2012, I researched both future saints before their canonizations — Damien in 2009 and Marianne in 2012. I visited all the sites linked to their lives and read whatever I could, especially personal writings and diaries. Theirs were such courageous stories — years dedicated to ministering to the victims of Hansen’s disease (leprosy) who lived in exile, mostly in unspeakable conditions, on a handkerchief-sized piece of land in the Pacific.

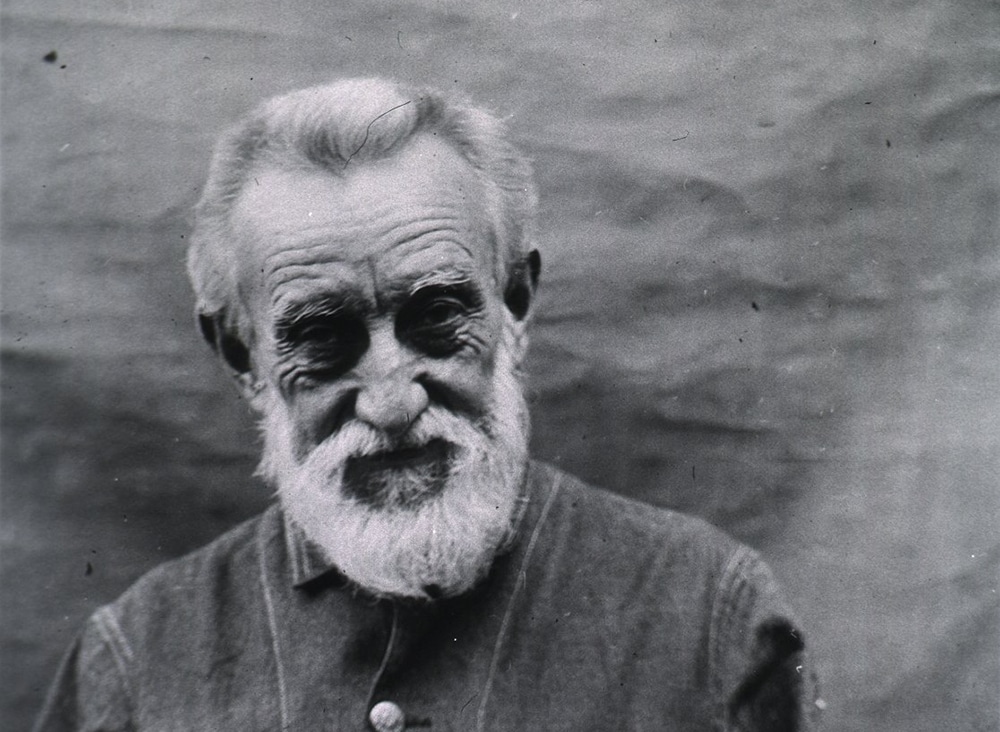

I also heard the stirring story of a layman, Joseph Dutton, who spent the last 44 years of his 88 years of life caring for the exiled and abandoned leprosy patients, assisting Father Damien in his last days on Kalaupapa, a peninsula on the island of Moloka’i, and then working with Mother Marianne and her Sisters of St. Francis for 30 years. Kalaupapa is where the victims of leprosy were exiled for life because of a law enacted in 1865 by King Kamehameha V and the Hawaiian legislature. More than 8,000 people are buried here, though many tombstones were washed away a long time ago in a tsunami.

During their fall assembly in Baltimore, the U.S. bishops will be presented with an update on Dutton’s canonization cause, which was initiated by the Diocese of Honolulu.

But who was Joseph Dutton, called “Brother Joseph” by St. Damien, “because you are like a brother to everyone here”?

Born Ira Dutton in 1843 to Protestant parents in Stowe, Vermont, some of his early years were spent in Janesville, Wisconsin, where he joined the Janesville Zouaves who later became the 13th Wisconsin Infantry in the Civil War. Dutton attained the rank of second lieutenant and received impressive assignments at a very young age, lauded for “his self-reliance, his initiative, and his ability to get willing service out of others.” One brigadier general said of Dutton, “He can be trusted in any position.” These qualities, along with “his confidence and thoroughness in everything he undertook” would serve him well in his later decades on Kalaupapa.

Dutton’s post-war years were traumatic times, “dark years” and “the degenerate decade” in his words. They were years when drinking became his nemesis. He even wrote at one point that “only God and I know what really happened in those years.”

However, Ira Dutton had an epiphany, a moment of awakening that he wrote about: “I lived for some years a wild life and felt that I should make some sort of reparation for it. … Throughout my life I was a firm believer in thoroughness in everything, and so I decided that my penance should be thorough; in other words, that the remainder of my life should be devoted to that, and to nothing else.”

Dutton realized he had to do penance for his past, and he saw that as happening in the Catholic Church.

Ira Dutton became a Catholic on his 40th birthday in April 1883 and took the name of a saint he loved: Joseph. He joined a Trappist monastery in Gethsemani, Kentucky, where he remained for 20 months. He left without taking vows, and on a visit to New Orleans, he read an article in a Catholic newspaper about Father Damien’s work with victims of leprosy in the Hawaiian islands.

According to Joseph: “It was a new subject and attracted me wonderfully. … After weighing it for a while I became convinced that it would suit my wants — for labor, for a penitential life and for seclusion as well as complete separation from scenes of all past experiences.”

Joseph now knew what he would do with the rest of his life. He took a train to San Francisco, a boat to Kalaupapa, and when he met Father Damien, who was always in port when a ship arrived, he told him: “I know what you do. I am here to help.”

And so he did, for more than 40 years. Wherever he saw a need, he rolled up his sleeves and helped out as cook, gardener, a sometimes doctor, carpenter, pharmacist, stonemason, accountant and secretary. He changed bandages on lepers and soothed fears. Joseph was a prolific writer — not only diaries but letters to anyone in the world (literally) who might be able to help the outcasts of Kalaupapa, from royalty to U.S. presidents to well-known authors. He became known worldwide for his humanitarian work.

“Brother Joseph” was loved by all for his constant smile, his ever-present serenity and his unfailing optimism.

He was Father Damien’s shadow until the saint’s death in 1889, as he was for 30 years afterwards with Mother Marianne. At one point, Mother Marianne helped him become a Third Order Franciscan.

As one Dutton prayer says, it was God’s grace that “raised him from the darkness of war, betrayal, addiction and despair to the liberating joy of charity in the service of the abandoned and isolated chronically ill.”

Today, with his cause for canonization underway, he is not just “Brother Joseph,” he is a Servant of God.

Joan Lewis writes from Rome.