God’s interventions that serve as turning points in people’s lives come in a multitude of forms. Sometimes it’s a single, dramatic event like St. Paul’s experience on the road to Damascus. Sometimes it’s the climax of a process stretching over months or even years — think of St. Augustine. And sometimes it’s a bit of both — dramatic event and process.

The conversion of St. Ignatius Loyola, from soldier to founder of the Jesuits, was a turning point of the third kind.

In God’s plan, Ignatius was meant to found — what historian Christopher Dawson calls “the most effective instrument for the reform of the Church” in the face of the Protestant Reformation — the Society of Jesus. But no one could have imagined Ignatius doing any such thing at the start or for many years after.

Early life

Ignatius was born in the Basque country of northern Spain on Oct. 23, 1491 — eight years after Martin Luther, the same year as King Henry VIII of England, and just a year before Columbus reached the New World. The family was members of the minor nobility whose menfolk traditionally took up soldiering as a trade. As a teenager, the boy became a page in the royal court of Castile, where for the next decade he busied himself with what his priest secretary — no doubt repeating his own words — calls “gaming, affairs with women, dueling, and armed affrays.”

Read more from the Turning Points series here.

Following the death of the royal official who’d been his patron, Ignatius, now 26, joined the army of the Viceroy of Navarre. The spring of 1521 found him leading the outnumbered, outgunned defenders of the city of Pamplona, then under siege by a French army. As was his custom, Ignatius fought valiantly — until a cannonball shattered his right leg. The conquering French, admiring his courage, transported him by litter to his family’s castle, and there he lay in an upper room, suffering alternately from pain — the injured leg had to be re-set, leaving him with a limp for the rest of his life — and from boredom.

Illumination

Before his injury, Ignatius had enjoyed reading romantic tales of knighthood and chivalry, but the only books in the castle were a life of Christ and a volume of saints’ lives. As he read these, he began to ask himself, “Mightn’t I do the same?” One night he had a vision of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus. And now he resolved to go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem as soon as he could.

First, though, he went to the great Marian shrine of Montserrat and there made a general confession. Before, he had worn elegant clothes. Now he dressed in rags, begged for alms and lived with the poor. Outside the nearby town of Manresa, he found a cave where he could be alone in prayer and meditation. Here for the first time he read Thomas à Kempis’ “Imitation of Christ” and was deeply impressed. Here, too, he received an “illumination” about some sort of spiritual militia in the service of God and began to write the book that became his famous Spiritual Exercises.

Spiritual Exercises

When finally he made it to the Holy Land, the Franciscans who had charge of pilgrims refused to let him stay and preach Christ to the Muslims as he had planned to do. Back in Spain and aware that he needed more than a rudimentary education if he was to be of service to the Lord, he began the long years of study that led him at last to the great University of Paris.

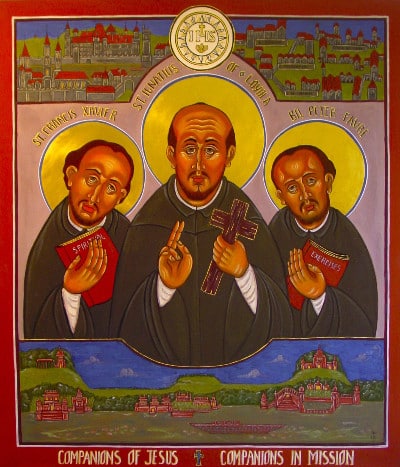

There Ignatius began attracting companions and disciples, among them Francis Xavier and Peter Faber, both destined to be canonized saints. For their formation, he used the Spiritual Exercises. This slim volume, widely used today just as when it was composed, is not a devotional work and can be dry reading for those who do not understand its purpose — to provide a guide for retreat masters seeking to elicit a lasting commitment to carry out God’s will on the part of someone making the exercises.

The book’s uncompromising spirit is suggested by the “Principle and Foundation” with which it begins:

“Man is created to praise, reverence, and serve God, our Lord, and by this means to save his soul. All other things on the face of the earth are created for man to help him fulfill the end for which he is created. … Man is to use these things to the extent they will help him to attain his end. Likewise, he must rid himself of them in so far as they prevent him from attaining it.”

Society of Jesus

After Mass on Aug. 15, 1534, Ignatius and his companions made a joint vow to commit themselves to God’s service. In 1537, the little group made its way to Rome, where they received the encouragement of Pope Paul III. Two years later, the Society of Jesus was formally established. Pope Paul III approved it in 1540, and Ignatius was chosen as Superior General for life.

At that time, the Jesuits were a novelty in many ways. Unlike other religious orders, they did not come together to recite the office. To the traditional three vows of poverty, chastity and obedience they added a fourth vow of loyalty to the pope by which they pledged to go wherever he sent them and take on whatever assignment he gave them.

Says Dawson: “All external rules and practices were reduced by [Ignatius] to a minimum. Everything was designed to make the Society as flexible and as united as possible so that it would be free to turn its energies in whatever direction they were needed.”

The Society spread rapidly throughout Europe and soon to the Americas and, via Francis Xavier, the Far East. Jesuits established schools, had important roles in the Council of Trent, wrote catechisms (St. Peter Canisius), preached and served as confessors and spiritual guides, and everywhere conducted retreats during which they led retreatants through the Ignatian Exercises. Although by no means the only force for Catholic reform, the Jesuits spearheaded the revival of Catholicism in the face of militant Protestantism that history knows (or anyway knew, before our ecumenical times) as the Counter-Reformation.

Ignatius now lived in Rome, supervising all this. Death came for him on July 31, 1556. By then, the Society he founded numbered 1,000 members engaged in a remarkable variety of activities, all directed, in the words of the Society’s motto, Ad majorem Dei gloriam — “To the greater glory of God.” One of his last acts was to write a fatherly letter to a young Jesuit encouraging him to persevere in his vocation.

Gifted guidance

Five hundred years later, a prominent American Jesuit, Father John LaFarge Jr., wrote of Ignatius that, thanks to the lessons he had learned in what he called “the School of Manresa,” he was “supremely fitted to guide, and teach countless others to guide, the human heart and will in the desperate struggle for decision, in the effective rejection of evil and total embracing of the good.”

St. Ignatius himself provided the best description of this particular “decision” and its substance in a well-known prayer that is part of the “Contemplation for Obtaining Love of God” near the end of the Spiritual Exercises:

“Take, O Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and all my will, all I have and possess. Thou hast given it all to me; to Thee, O Lord, I restore it: all is Thine; dispose of it according to Thy will. Give me Thy love and Thy grace, for this is enough for me.”

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.