In the 25 years since Pope St. John Paul II published an encyclical called Veritatis Splendor — “The Splendor of Truth” — the document has established itself as not just the most discussed piece of writing by this very prolific pope, but very likely the most important.

Over the centuries, other popes have often taught about specific issues of personal and social morality. But Veritatis Splendor stands alone among papal documents in that it sets out fundamental principles of moral reasoning that underlie the Church’s moral teaching and presents the philosophical and theological case against dissent.

‘Crisis of truth’

Explaining why he considered it necessary to take this step, Pope John Paul cited a “crisis of truth” that he said was afflicting contemporary society and had spread since the 1960s to Catholics via theological dissent.

“It is no longer a matter of limited and occasional dissent, but of an overall and systematic calling into question of traditional moral doctrine,” the pope wrote. On the contrary, he said, at its root are “currents of thought which end by detaching human freedom from its essential and constitutive relationship to truth” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 4).

The process of producing the encyclical reflects the seriousness with which John Paul viewed this problem.

He announced his intention to write such a document six years earlier, in 1987.

The years that followed brought the publication in 1992 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which contains a definitive statement of Catholic teaching on particular issues. Pope John Paul said it was important that this precede the encyclical.

During this time, too, the pope conducted a broad consultation on the encyclical with the bishops of the world. To them, as official teachers in the Church and voices of the magisterium, Veritatis Splendor is first of all directed.

Finally, on August 6, 1993, Pope John Paul signed the final text of the encyclical. It was publicly released by the Vatican on October 5 of that year.

Encyclical roots

The document arises in part from John Paul’s own experience in earning doctorates in philosophy and theology and teaching as a member of the philosophy faculty at the University of Lublin in his native Poland.

Overall, it is something of a hybrid, combining elements of a textbook in ethical theory with passages of a homiletic nature. While the sections that argue technical points in moral philosophy are likely to be difficult for some readers, the sections that are of an inspirational nature are uplifting and relatively simple.

Veritatis Splendor is notable also for its grounding in Scripture and its Christocentric character — its focus on Christ as source and model of Christian morality — which the Second Vatican Council said should characterize an updated moral theology.

The text leaves no doubt about the pope’s intention in writing it.

“The specific purpose of the present Encyclical,” it says, “is … to set forth, with regard to the problems being discussed, the principles of a moral teaching based upon Sacred Scripture and the living Apostolic Tradition, and at the same time to shed light on the presuppositions and consequences of the dissent which that teaching has met” (No. 5).

But although Veritatis Splendor aims at refuting errors, it takes an essentially positive approach to its subject — morality — stressing the attractiveness of a life lived according to authentic norms of ethical behavior. In doing so, it lays out an inspiring, though admittedly challenging, vision of the morally good life as the path that leads to human fulfillment in Christ and happiness in this world and the next.

Chapter I: Matthew’s Gospel and the rich young man

After an introduction explaining its background and John Paul’s reason for writing it, the encyclical has three chapters. The first is largely an extended reflection on the dialogue in Chapter 19 of St. Matthew’s Gospel between Christ and a rich young man who comes to him asking what he must do to “gain eternal life” (Mt 19:16).

In reply, Jesus tells him to keep the commandments. And when the young man asks which ones, Jesus answers by citing those that involve relationships with other people. But the young man says he already does that — what next? Jesus’ reply is not what he expected: “‘If you wish to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to [the] poor, and … come, follow me'” (Mt 19:21).

“When the young man heard this statement,” Matthew writes, “he went away sad, for he had many possessions” (Mt 19:22).

Commenting on this, John Paul says that Jesus extends an invitation to the young man to “enter upon the path of perfection.” And where in Scripture is that to be found? The pope’s answer is: in the Sermon on the Mount and the Beatitudes, which he calls “a sort of self-portrait of Christ.” As a program for Jesus’ followers, the Beatitudes require “mature human freedom” — but they also mark out precisely the way one grows in freedom.

In his moral teaching, Jesus does not abolish the commandments but brings them to fulfillment while, at the same time, pointing beyond them. His program is not a kind of moral minimalism or legalism but something much greater: “The commandments must not be understood as a minimum limit not to be gone beyond,” John Paul writes, “but rather as a path involving a moral and spiritual journey toward perfection, at the heart of which is love” (No. 15).

Here the pope makes one of the most important points in the entire encyclical: The “journey toward perfection” is not meant only for a spiritual elite group but is intended for all Christians without exception. Another name for it is Christian life.

He writes:

“Both the commandments and Jesus’ invitation to the rich young man stand at the service of a single and indivisible charity, which spontaneously tends toward that perfection whose measure is God alone. … The way and at the same time the content of this perfection consist in the following of Jesus. … It involves holding fast to the very person of Jesus, partaking of his life and his destiny, sharing in his free and loving obedience to the will of the Father. … Jesus’ way of acting and his words, his deeds and his precepts constitute the moral rule of Christian life” (No. 18, 19, 20).

Chapter II: Against proportionalism and consequentialism

The second chapter, the encyclical’s longest, is titled “The Church and the discernment of certain tendencies in present-day moral theology.” Here is where John Paul sets out the case against dissent.

The fundamental point can be stated simply: Some ways of acting are “intrinsically evil” — they involve acts that can never be rightly chosen and performed. Theories of morality that argue otherwise are wrong and conflict with the “way” to which all Christians are called.

This leads John Paul to reject so-called “pastoral” solutions to people’s problems that proceed by separating moral precepts from particular cases and leaving it to the consciences of individuals to “make the final decisions about what is good and what is evil” (No. 56).

After considering the true nature and role of conscience, Veritatis Splendor moves on to an extended discussion — the very heart of the encyclical, the reader feels — of contemporary ethical theories that go by the names “proportionalism” and “consequentialism.”

As a practical matter, the most important thing about these offshoots of 19th-century utilitarianism — and also most alarming — is that they make it impossible to rule out in advance any kind of action on the grounds that it is always and everywhere wrong, in every time and place and under all circumstances.

This is not to say proportionalists and consequentialists are bad people looking for excuses to do bad things. But the moral theory they subscribe to says that, in every situation involving a choice among several options, one should weigh the consequences of different courses of action and choose the way of acting that promises to produce the best “proportion” of good results to bad.

The American ethicist and moral theologian Germain Grisez, who died earlier this year, was a strong opponent of proportionalist and consequentialist thinking who produced a devastating critique showing why these theories are wrong.

He argued, among other things, that they are unworkable: first, because they require something impossible — knowing what all the consequences of a particular act will be — and then because they require a kind of “apples and oranges” exercise in which fundamentally different goods are measured against one another.

In Veritatis Splendor, Pope John Paul reviews considerations like these and then concludes: “The morality of the human act depends primarily and fundamentally on the ‘object’ rationally chosen by the deliberate will. …” And the test of that object is whether it is “capable of being ordered to God” as its ultimate end (No. 78, 81). This, he adds, is why a good intention by itself does not make an otherwise immoral act good, like killing the innocent or adultery.

By way of example, John Paul mentions some intrinsically bad acts named in a non-exhaustive list, included by the Second Vatican Council in its Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World: “Whatever is hostile to life itself, such as any kind of homicide, genocide, abortion, euthanasia and voluntary suicide … whatever is offensive to human dignity, such as subhuman living conditions, arbitrary imprisonment, deportation, slavery, prostitution and trafficking in women and children; degrading conditions of work which treat laborers as mere instruments of profit and not as free responsible persons” (No. 80).

Under this heading, too, he cites the teaching that every act of contraception is intrinsically wrong.

Chapter III: The consequences of ethical relativism

The third and last chapter of the encyclical is “Moral good for the life of the Church and of the world.” As that suggests, having considered morality in its personal dimensions, Pope John Paul now turns his attention to morality’s social and political implications.

Here the pope identifies a cluster of values that he says are important in political society — truthfulness, openness, respect for opponents, fairness in judicial proceedings and refusal to pursue “power at any cost.”

Here, too, he makes an important point that needs to be heeded today in the United States and other Western democracies, where controversies erupt over government efforts to force people with conscientious objections to cooperate with legalized abortion and same-sex marriage. In the United States, cases raising this issue came before the Supreme Court during its last term.

| On Martyrs |

|---|

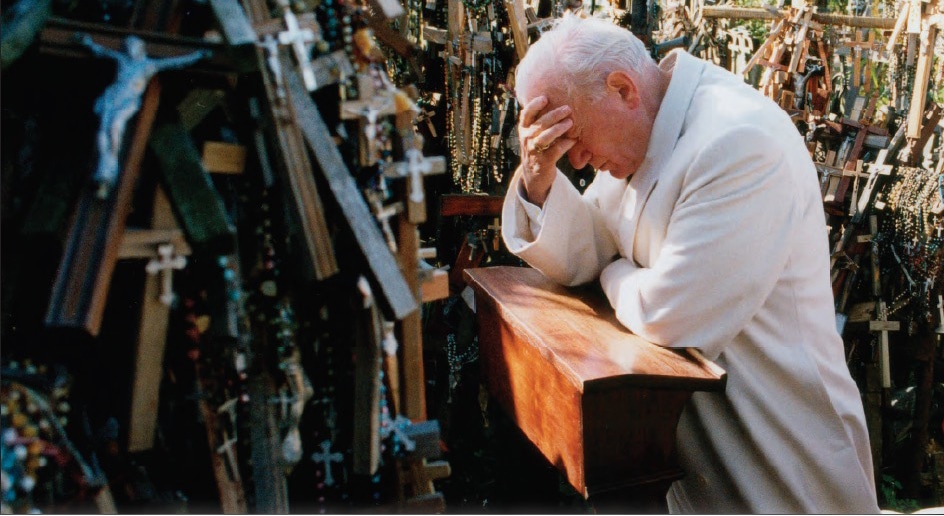

|

Near the end of Veritatis Splendor, Pope St. John Paul II includes a section on the martyrs. The purpose is not just to make the pious point that these men and women lived morally good lives capped by accepting death rather than sinning, but also to underline another point that lies at the heart of the encyclical.That point, in John Paul’s words, is the absolute inviolability of “those moral norms which prohibit without exception actions which are intrinsically evil.” Recalling an argument that he makes at length earlier in the document, he says the existence of absolute norms that are always wrong and may never be violated underlines the error of “proportionalist” and “consequentialist” ethical theories that underlie much contemporary dissent from the Church’s moral doctrine (No. 90). Moreover, the pope goes on to say, in canonizing the martyrs, the Church testifies to “the truth of their judgment, according to which the love of God entails the responsibility to respect his commandments, even in the most dire of circumstances, and the refusal to betray those commandments, even for the sake of saving one’s own life” (No. 91). “Martyrdom rejects as false and illusory whatever ‘human meaning’ one might claim to attribute, even in ‘exceptional’ conditions, to an act morally evil in itself,” he says (No. 92). |

“This is the risk of an alliance between democracy and ethical relativism, which would remove any sure moral reference point from political and social life, and on a deeper level make the acknowledgment of truth impossible,” John Paul says (No. 101).

Then he adds a warning taken from his 1991 encyclical Centesimus Annus on the fall of communism: “As history demonstrates, a democracy without values easily turns into open or thinly disguised totalitarianism” (No. 101).

After discussing the service that moral theologians can and should render to the whole Church, John Paul concludes the encyclical by invoking the intercession of the Blessed Virgin. Being sinless herself, he says, “she is on the side of truth and shares the Church’s burden in recalling always and to everyone the demands of morality” (No. 120).

Like morality, Veritatis Splendor is frequently challenging. But — also like morality — the rewards for those who make the effort to absorb what the encyclical says are also very great.