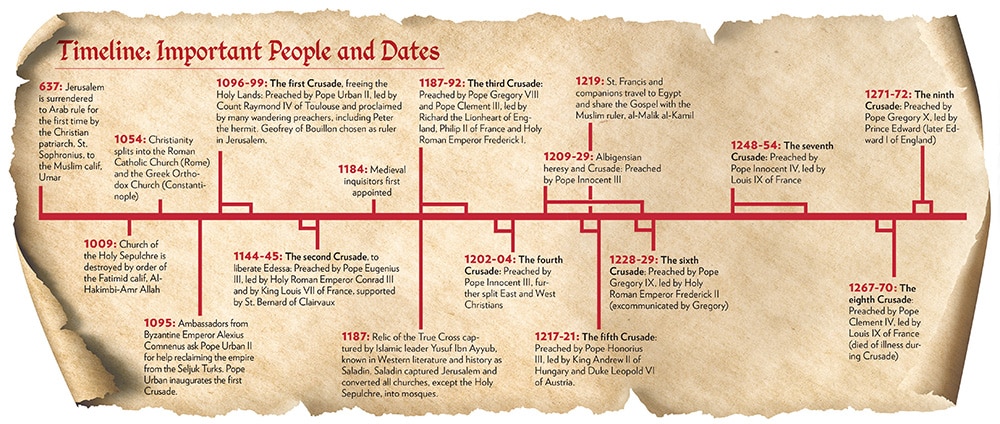

Most often we associate the term “Crusades” with an effort by the European Christians of the Middle Ages to take back the Holy Land, specifically Jerusalem, from the Muslims. Indeed, there were Crusades mounted for that reason. Popes from the 11th to the 13th centuries believed it was their duty to save the lands where Jesus had walked, had lived and was resurrected from the infidels, the non-Christians. There was also another Crusade toward the end of that same era mounted to confront heretics in Europe, especially in France. Enemies existed outside the Church from the Muslims and inside from heretics.

Crusades against Muslims

By the ninth century, Muslims controlled much of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine) and occupied many Christian cities, including Jerusalem. The Christians living in Jerusalem were allowed to coexist with the Egyptian Muslims (Fatimids-Arabs) and access to holy sites was permitted. But it was a precarious coexistence, depending on the leader of the Fatimids. At one point, the Muslims turned on the Christians, and in 1009 the Church of the Sepulcher was destroyed, only to be rebuilt with permission of the Fatimids.

In 1071, the Seljuk Turks became the dominate Muslim group in the Middle East, and they occupied Jerusalem. Their attitude toward Christians was one of belligerence and even hatred. They murdered Christians, desecrated some of the holy sites and stopped the Christian pilgrimages to all of those sites. Stories about the ill treatment of Christians were soon circulating in in Europe. At that time Emperor Alexius Comnenus (1081-1118) was the leader of the Eastern Roman Empire, an empire that largely had been reduced to the city of Constantinople. Alexius pleaded with Pope Urban II (r. 1088-99) for help against the Turkish aggression.

Pope Urban was revolted by the fact that Christians were being persecuted, murdered and denied access to Jerusalem, the holiest city in Christendom. This is the city where Jesus entered triumphantly on Palm Sunday before he was crucified, died and buried. This city contains the roots of Christian ministry from Christ’s first disciples.

Pope Urban was revolted by the fact that Christians were being persecuted, murdered and denied access to Jerusalem, the holiest city in Christendom. This is the city where Jesus entered triumphantly on Palm Sunday before he was crucified, died and buried. This city contains the roots of Christian ministry from Christ’s first disciples.

Psalm 137 speaks to all Christians: “If I forget you, Jerusalem, may my right hand forget. May my tongue stick to my palate if I do not remember you, If I do not exalt Jerusalem beyond my delights.” Jerusalem was so important to the Christians that popes encouraged warfare to keep the city open to the faithful.

Additionally, Urban, like Pope St. Gregory VII (r.1073-85) before him, was looking for a way to reunite the Latin and Greek Churches, which had been separated since 1054. He saw the opportunity to bring the Greek Church back into the fold of the Holy See, rescue Eastern Christians and save Christian lands from the Turks. He decided he would use a Crusade — a holy war — in an attempt to do so.

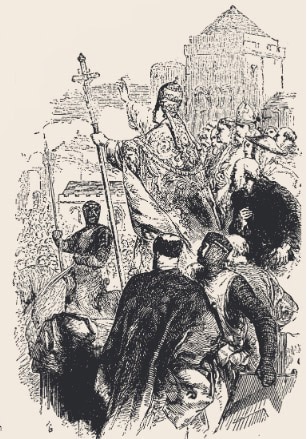

At the Council of Clermont, France, on Nov. 27, 1095, Pope Urban preached (crusades were ordered by “preaching”) the first Crusade. His words were inspirational to the audience, which mostly consisted of Frenchmen:

“From the confines of Jerusalem and from Constantinople a grievous report has gone forth that an accursed race, wholly alienated from God, has ardently invaded the lands of these Christians, and has depopulated them by pillage and fire. They have led away a part of the captives into their own country, and a part they have killed by cruel tortures. They destroy the altars, after having defiled them with their uncleanliness. The kingdom of the Greeks is now dismembered by them. …” He went on in a rousing speech to challenge Christians: “On whom, then, rests the labor of avenging these wrongs, and of recovering this territory, if not up upon you-you upon whom, above all others, God has conferred remarkable glory in arms, great bravery, and strength to humble the heads of those who resist you? … Let the Holy Sepulcher of Our Lord and Savior, now held by unclean nations, arouse you, and the holy places that are now stained with pollution. … Let none of your possessions keep you back, nor anxiety of your family affairs. …” He told his listeners that rather than fight one another, to turn their combined might against the invader. Pope Urban added: “Undertake this journey eagerly for the remission of your sins, and be assured of the reward of imperishable glory in the Kingdom of Heaven” (“The Age of Faith,” Will Durant).

Pope Urban envisioned a single army of knights supported by foot soldiers as comprising a Crusade, but it turned out to be somewhat different. People from every walk of life wanted to go; rich, poor, nobles, knights, serfs and religious all became Crusaders. Some considered this a protective or adventurous pilgrimage, while others joined out of greed or for glory. But most were motivated by the cause to take the Christian lands back from the Muslims. Many Crusaders left their homes and gave up their livelihoods, knowing they might not return. They left because they believed they were being called by God. The pope contributed to this attitude by offering an indulgence to anyone who went on the Crusade. He promised if they died in combat, all their sins would be forgiven and they would attain eternal life.

| Motivation for the Crusades against the Muslims |

|---|

Often writers play down the holy motivation of the Crusaders who “took up the cross” desiring to protect other Christians, to make a pilgrimage and to pray at the Holy Sepulcher. Instead, some writers focus on those participants, and there were many, who participated out of greed and glory. In his book “Indulgences, their Origin, Nature and Development,” Cardinal Alexius Lepicier responds to that perception: “Such writers as are wont to judge of a work by its effects, or reckon others’ ardour by their own coldness, will not see in the Crusades anything but the swelling of fanatic enthusiasm, and a door opened to licentiousness and to the relaxation of morals, similar to those observers whose judgment of a noble monument is guided only by the consideration of some defective details. “For us, apart from the result of these enterprises, and the defects inherent to every human institution, we cannot but recognize in the motives that prompted these immense levies of men, and in the disinterestedness with which these brave knights left the comforts of their homes, the signs of a generosity of heart and of a quickness of faith which is the greatest praise of the character, both civil and religious, of the Middle Ages. “However, the Crusades, acknowledged unanimously by the people to be God’s holy will, are among those events ordained by Divine Providence to be, for the Church, a means of asserting her vitality, of tending to fuller growth, and to an ampler display of her discipline.” For the individual Crusader, this was a Christian duty. |

The first Crusade

The first Crusade was not one army, but four different contingents recruited to fight the Muslims. The groups were from Germany, Italy and multiple regions in France. The total number of participants was estimated at as many as 100,000 individuals. But likely less than half of that number were true combatants. The noncombatants included people from all parts of society, including family members and servants. The different forces planned to rendezvous at Constantinople.

Some Crusaders started out in advance of the four main groups. They were disorganized, poorly prepared, undisciplined and included few professional soldiers. Inspired to confront any nonbelievers in the Middle East, they attacked Jews living in Europe. Because Jews had killed Christ, these Crusaders demanded that the Jews they encountered either convert to Christianity or die, despite protective papal edicts. Many Jews were murdered. The news of the atrocities committed by this group preceded them into the countries where they needed support, since they lacked necessary provisions. This was not a good start.

All the different groups comprising the first Crusade were impacted by famine and disease. There was little communication between groups, inconsistent leadership and confrontations with the Turks. There were also many desertions, but eventually a contingent of some 12,000 combatants reached Jerusalem on June 7, 1099, and attacked the Muslim forces holding the city. The Christians overran and pillaged the city, executing the nonbelievers. The atrocities committed by the Crusaders further fueled Muslim hatred for Christians.

After conquering the holy city, the victors urged their leader, Geofrey of Bouillon, to take the title “King of Jerusalem.” He refused, saying: “I will never wear a golden crown where the Redeemer was crowned with thorns.” He preferred to be called “Defender or Baron of the Holy Sepulcher.” Jerusalem was established as a kingdom that included the countries of Edessa and Tripoli, and the principality of Antioch. These areas became known as Crusader States.

Having taken Jerusalem, the Crusaders began to depart back to Europe, leaving around 300 knights behind. The time between 1100 and 1120 saw the formation in Jerusalem of several military orders: Hospitallers, Templars and Teutonic Knights. Even with these highly regarded groups, the Byzantine and Crusader Christians could not hold the Crusader States indefinitely. For a while, the Christians were aided by the internal debates and divisions among the Muslims. Soon, strong Islamic leaders emerged, and by the middle of the 12th century, Muslims were recapturing the lands taken by the Crusaders and would soon threaten the entire Middle East.

| Why did people volunteer for the Crusades? |

|---|

“Although there is no simple explanation for the overwhelming response to Urban’s call for the Crusade, one factor outweighs others and provides the most meaningful answer: faith. Medieval people were steeped in the Catholic faith; it permeated every aspect of society and their daily lives. They saw Urban’s call to the Crusade as a unique, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to provide for their spiritual health and increase their chance of salvation. In this vicious and violent age, most laymen, especially the nobility, believed it was extremely difficult for those not in a monastery to go to heaven. The Church constantly warned warriors that warfare over land holdings against fellow Christians placed their souls in danger, providing sufficient motivation for many to take the cross. … Crusaders went to war not only for reasons that men have gone to war for centuries — glory, adventure, love of country — but also because they embraced the Crusade as a unique opportunity to participate in their salvation and give a witness of their love for God.” “Although there is no simple explanation for the overwhelming response to Urban’s call for the Crusade, one factor outweighs others and provides the most meaningful answer: faith. Medieval people were steeped in the Catholic faith; it permeated every aspect of society and their daily lives. They saw Urban’s call to the Crusade as a unique, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to provide for their spiritual health and increase their chance of salvation. In this vicious and violent age, most laymen, especially the nobility, believed it was extremely difficult for those not in a monastery to go to heaven. The Church constantly warned warriors that warfare over land holdings against fellow Christians placed their souls in danger, providing sufficient motivation for many to take the cross. … Crusaders went to war not only for reasons that men have gone to war for centuries — glory, adventure, love of country — but also because they embraced the Crusade as a unique opportunity to participate in their salvation and give a witness of their love for God.”

Read more in “Timeless: A History of the Catholic Church” (OSV, $19.95) by Steve Weidenkopf from osvcatholicbookstore.com. |

Second and subsequent Crusades

Following the first Crusade, there were at least six more major attempts to recapture the sacred sites of Jesus. None were successful in terms of establishing a permanent Christian reign in the Middle East.

Among those advocating a second Crusade, no one was more influential than St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153). He, along with Blessed Pope Eugenius III (r. 1145-53), began to recruit volunteers almost immediately after Edessa fell to the Turks in 1144. Bernard said to potential Crusaders: “The earth trembles and is shaken because the King of Heaven has lost his land, the land where he once walked. … The great eye of Providence observes these acts in silence; it wishes to see if anyone who seeks God, who suffers with him in his sorrow, will render him his heritage. … I tell you, the Lord is testing you” (“A History of Medieval Europe,” R.H.C. Davis). Two expeditions, one commanded by German Emperor Conrad III (r. 1138-52) and the other by King Louis VII of France (r. 1137-80), set out in 1147. Their common destination was Constantinople, but there was almost no coordination or common course of action, and many soldiers were killed along the way. While some Crusaders eventually placed Damascus under siege, they later abandoned the effort and returned to Europe in 1149.

| St. Bernard of Clairvaux |

|---|

Born in France to a noble family, Bernard joined the Cistercian order, where he embraced the austere lifestyle. He even convinced four of his brothers, an uncle and several other young noblemen to commit their lives to the order. After professing vows, the abbot sent him and 12 others to establish a monastery in Clairvaux. Bernard became abbot of this monastery, and he soon founded numerous other monasteries. He wrote Pope Eugene III and asked him to preach the second Crusade, and he traveled through France and Germany to encourage Christians to fight for their faith. He died in 1153 and is considered a Doctor of the Church.

|

A third Crusade was preached by Pope Clement III (r.1187-91) after Jerusalem fell to the Muslims led by Saladin in October of 1187. Frederick Barbarossa (r. 1152-90), King Philip Augustus of France (1180-1223) and King Richard the Lion-Hearted of England (1189-99) agreed to lead this Crusade. While they were all able to successfully reach the Middle East, they constantly questioned each other and refused to cooperate or compromise. Ultimately, even with overwhelming forces, the Crusaders failed to capture Jerusalem. Saladin remained in control.

The fourth Crusade, which took place from 1202 until 1204, was urged by Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216). Unfortunately, the crusading armies — against the wishes of Innocent — attacked and sacked Constantinople, the Byzantine capital. Indeed, the Latin Christians murdered Greek Christians. The Crusaders established one of their own as a Latin emperor over the Byzantine empire. The Crusaders had produced another obstacle to the unification of Western and Eastern Christians under the papacy. The Latin control of Constantinople lasted for 50 years, until the Byzantines wrested it back.

After four failed attempts, the West concluded that Egypt was the key to winning in the Middle East. In 1217, Pope Innocent III encouraged a fifth Crusade designed to capture the Muslim forces in Egypt. Made up of Crusaders from Hungary, Austria and Germany, they first met with success by conquering cities on eastern mouth of the Nile. From here, they attacked Cairo. But again, lack of leadership and infighting brought failure to the Crusaders, and by 1221 they had evacuated Egypt in defeat.

In 1228, Frederick II, Emperor of the Roman Empire — and who had been excommunicated — led the sixth Crusade into Palestine, where he signed a treaty with the Muslims that restored the cities of Nazareth, Bethlehem and much of Jerusalem to the Christians. All prisoners were released, and 10 years of peace was promised. Pilgrims could once more visit the sacred sites of Jesus. An excommunicated ruler had more success in less time with fewer casualties than any of the other Crusades. The peace lasted until 1244, when the Turks rose up and Jerusalem once more belonged to the Muslims.

During the years 1248 to 1254, and from 1267 to 1270, the great St. Louis IX, King of France, led two Crusades into Egypt. In 1248 he captured Damietta, at the mouth of the Nile, but was stopped by flooding. During a six-month delay, his forces were depleted by disease and desertion. The Crusaders were soon defeated and many of them, including King Louis, were captured. After paying a huge ransom, he and his men were released. Louis remained in the Middle East for four years, constantly asking for reinforcements. None arrived. In 1254 he marched back to France.

In 1270, Louis headed another Crusade, landing his forces into Tunisia and seeking to attack Egypt from the west. Almost as soon as they arrived, Louis fell sick and died of a stomach disease. The Crusaders continued their march and some committed terrible atrocities against Muslim communities. The Muslim leaders wanted the culprits, and when the Christians refused, many Crusaders were massacred. Some 60,000 were taken as slaves. This was the last significant Crusade against Islam to take back the Holy Land.

It is difficult to argue with those who say the Crusades were a military failure. Following 200 years of Crusades, during which over a million people died, Muslims still controlled Jerusalem and the Middle East. The desire of the papacy to reunite Christians of the East and West was also negated by the Crusades.

However, there were some positive results. European Christians united in a common cause; instead of fighting one another, they fought the nonbelievers who were persecuting other Christians. A spiritual revival of sorts took place; the Crusaders confronted Islam in the Middle East and kept their forces from increasingly expanding into Europe. A new world of knowledge was discovered, as well as expansion of commerce.

European Crusade against heretics

During the 12th century, a group of heretics rose up that countered many beliefs of the Church. Known as the Albigensians and named after the town of Albi in France, they followed the long-held views of the Cathari (from a Greek word meaning “pure”). Cathari doctrine was anti-Catholic. For example, they rejected the sacraments, including marriage, and preached against procreation and the family unit. On the other hand, they taught that concubinage, abortion and suicide were acceptable. Such ideas contradicted the teachings of Jesus and were abhorrent to most people. Europe was totally Roman Catholic and the Church was woven into every part of society; thus, an attack on religion was an attack on the state.

The Albigensians promoted dualism, claiming that the world was divided into good and evil, and that all spiritual things are created by God and are good. Conversely, the visible or material world was created by Satan and is bad. These heretics rejected Church authority by intentionally defying the pope and refuting the belief in the Incarnation. They denied the Real Presence in the Eucharist, the humanity of Christ and that he was crucified, died and resurrected. Jesus, they claimed, was a spirit or an angel, but not God. They also opposed many civil laws, rejecting the right of the state to wage war or impose capital punishment. In sum, their beliefs and practices were contrary to both the Gospel and good order. Unfortunately, they had a growing group of followers who favored this heretical conglomeration over the Catholic Church, which many considered corrupt and polluted. Because of their worldly lifestyles, priests were seen as liars and hypocrites.

Initially, Church bishops were responsible for dealing with the heretics and attempted to do so through peaceful reforms, missionary efforts and excommunication. These ad hoc methods were mostly ineffective. Pope Innocent III tried to solve the Albigensian problem for 10 years. He dispatched personal representatives to France, appointed new bishops and directed public interface with the heretics. But all these actions failed. The foundation of the Church, the teachings of Jesus and peace within the nation-state were increasingly at risk.

Finally, in 1209, Pope Innocent preached for a Crusade against the Albigensians, recruiting assistance from Northern France and various countries of Europe. Some individuals refused to wage war against other Christians, so Innocent offered a plenary indulgence to those who would participate. This was a disaster, as the Crusaders massacred men, women and children, with little regard as to whether or not they were heretics. Some towns in southern France were burned to the ground. A papal legate allegedly said to “Kill them all, God knows his own.” As towns were taken, some of the heretics were offered the chance to give allegiance to the Catholic Church or suffer death. Thousands chose death. Such warring efforts continued off and on for several years. Finally, in 1229, peace was achieved. The anti-Church groups were scattered but not totally suppressed. Pope Gregory IX (r. 1227-41) was confronted by the survivors of the heretical groups in southern France, as well as new elements in Italy and the Balkans. To deal with these dissenters, the Church turned to papal inquisitions. This Crusade wiped out much of the Albigensian heresy, but the cost was enormous.

D.D. Emmons writes from Pennsylvania.