A parishioner asked me once if I’d ever refuse holy Communion to President Joe Biden. Her tone made clear it was a test.

In the headlines again, I assume she just wanted to know where I stood. The problem was, though, I didn’t know where I stood. To this day, I don’t know where I stand or even if I should stand at all. Maybe it’d be better to find a cave somewhere. At least that’s how I felt at the time.

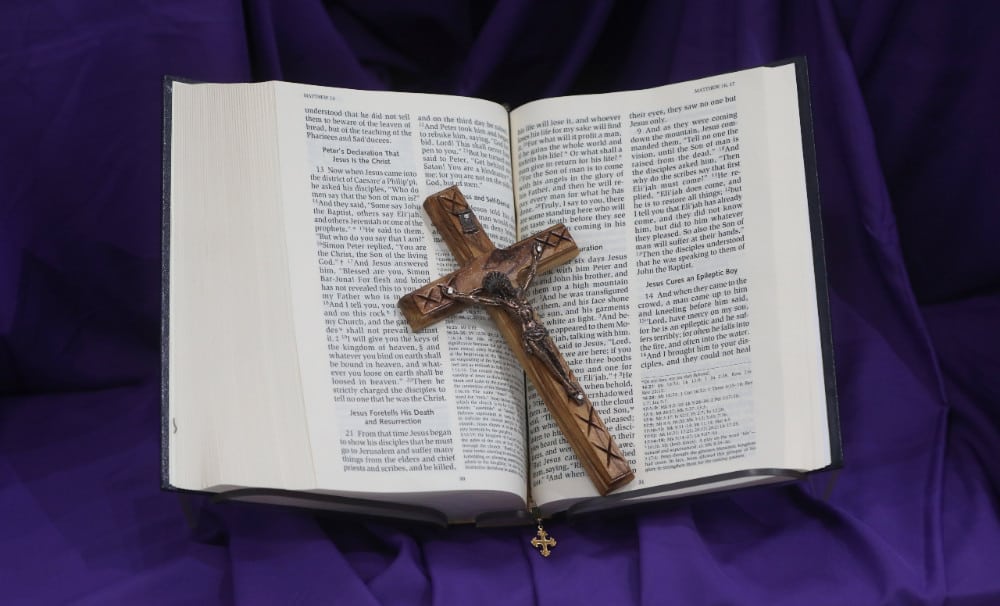

The question unsettled me, still does. You see, to be a priest, to give the body of Christ to someone, that’s a beautiful moment for me, each moment singular and unpoliced. It’s hard to describe, but I find the question — would I give or deny so-and-so Communion — nauseating and spiritually traumatic. Call me weak and wavering if you want; I barely know what to tell you aggressive types about anything anyway. It’s just that offering Communion to the People of God, for me, is something far removed from such agitated questions. What would I do if the president came to my parish? I don’t know; only God knows. And he’s not told me.

However, don’t count me among those up in arms over Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone of San Francisco prohibiting Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi from Communion. That’s not me, either. As a bishop, it’s quite within his authority; it may even be his duty. To accuse the archbishop of politics, that it’s out of bounds for him to exercise episcopal authority in this manner — in relation to a politician not only actively dissenting from clear Catholic teaching but also justifying it by a plainly bizarre, mistaken read of her own professed Catholicism — is clearly to mistake the tradition. And, I suspect, willfully.

Ever since Christ called Herod a fox, since he stood bloody before Pilate, preachers of the Gospel have, on occasion, necessarily opposed the political powers of the world, and not just by preaching but also by discipline. Any reader of First Corinthians knows this. Any reader of the tradition knows this: Augustine each Christmas preached against gladiatorial shows; the Cappadocians and Chrysostom preached against the rich and imperial; Gregory VII against Henry IV; Oscar Romero against the military junta of El Salvador. The bishops of Chile excommunicated agents of the secret police, and the archbishop of New Orleans once excommunicated segregationists. This is what real Christianity sometimes looks like: genuine Eucharistic life that is morally serious, that includes actual discipline. Now, we conditioned individualists, good Western pietists both Catholic and Protestant, have difficulty accepting this; we can barely fathom sacramental discipline at all. But that’s because we’ve mostly sentimentalized the Faith into meaninglessness. Because the Faith’s become for many of us merely aesthetic, a therapy, family legacy, cultural reflex.

Spiritually disciplining politicians, then, is nothing new or scandalous; rather, it’s the biblically traditional modus operandi of the Church. The question, then, is not whether a bishop can exercise apostolic authority but whether this particular application of ecclesiastical discipline is appropriate. And here, I only say that I’m grateful I’m not a bishop, that I’ll never be one; and also, that my opinion doesn’t really matter.

But, for what it’s worth, I do think applying Eucharistic discipline to politicians like Pelosi is appropriate. My only wish is that we would exercise such discipline more widely, and for matters not just related to abortion. For we have a lot of bad Catholics in public office — being from Texas, I should know — and they could probably benefit from similar discipline.

It’s appropriate because when a Catholic politician justifies something gravely contrary to the faith he or she professes, it bears false witness in such a public manner that it confuses not only the moral witness of the Church but also the integrity of its visible communion. That’s how Nancy Pelosi is different from other less public Catholics simply struggling to agree with Church teaching. Barring someone from Communion, especially a public figure, can be an act of radical reconciliation and healing in the Church. Because it makes truth visible, clarifying that the person excluded from the Eucharist has already excluded himself or herself from the Church by his or her own actions, and that what he or she is doing is unacceptable for members of the Church. The Church, by this act of discipline, is simply making that clear, and in that sense, is practicing mercy. For it’s seeking to protect such people from participating in the Eucharist unreconciled, which Paul made clear was a dangerous thing to do (cf. 1 Cor 11:29-30).

So, is barring Pelosi from holy Communion appropriate? Maybe not. But then again, maybe it’s the most honest invitation to follow Jesus she’s ever received from the Church. Maybe this is the first time in a long time the Catholic Church has ever been honest with her. Again, I don’t know. As I said, I’m glad I’m not a bishop. But maybe we should want to see more politicians called to account. Maybe we should desire such discipline for ourselves, or at least that we all take the moral demands of Catholicism a bit more seriously. Which might be just what the world needs.

Father Joshua J. Whitfield is pastor of St. Rita Catholic Community in Dallas and author of “The Crisis of Bad Preaching” (Ave Maria Press, $17.95) and other books.