Time flies. So do memories, especially after 60 years.

Time flies. So do memories, especially after 60 years.

During the afternoon of Oct. 22, 1962, the White House said that President John F. Kennedy would address the nation on a matter of grave importance. Every network telecast the speech. Rare was the American household not watching. When the president went off the air, rare was the American who slept soundly that night.

Kennedy revealed that the Russian government had positioned missiles, equipped with nuclear bombs, in Cuba, aiming them at targets in this country.

If fired, it was predicted, life in America would never be the same. Major cities — New York, Denver, Chicago, Dallas, Minneapolis, Los Angeles — would be no more. Because of radiation in the winds, McCall, Idaho; Cedarburg, Wisconsin; Exeter, New Hampshire; and Monroeville, Alabama also would be no more. Likely, a third of the population would be annihilated.

For 13 days, fear paralyzed everyone. Parents kept children home from school. One man in Ohio wrecked his car, rushing home from work to die with his family.

Catholic churches offered sacramental confessions around the clock. Like Christmas and Easter, churches were filled with parishioners on their knees.

During his remarks, Kennedy warned the Russians that firing any missile would prompt a “full retaliatory response” by this country — namely, American missiles fired at Russia, making the extinction of humanity a distinct possibility.

Kennedy demanded removal of the missiles. The Russians flatly refused. American allies Britain and France, with their own nuclear missiles, and others, were thinking about getting into the act.

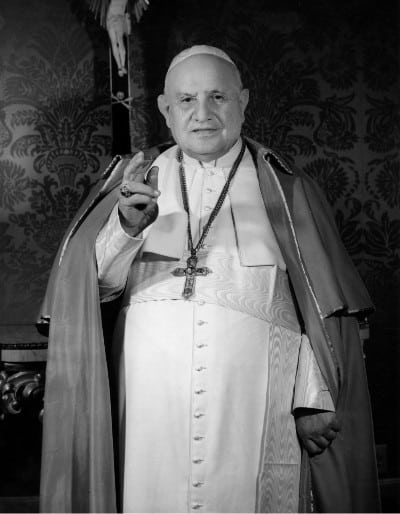

Approaching desperation, the president contacted Pope St. John XXIII, asking the pope to do anything that he could to get the missiles out of Cuba. “Good Pope John” reminded Kennedy that the Russians hardly were eager to hear papal advice, but, realizing that human life itself was at stake, the pope said that he would try to think of something, and he would appeal to God for mercy.

Apparently, Kennedy himself also appealed to God. Interrupting a critical meeting, he went to confession and Mass at Washington’s St. Stephen’s Church, near the White House.

Pope John was scheduled to give routine remarks in Rome on Oct. 25. The Vatican alerted the news media. The pope’s statement would be more than routine.

When he spoke, the pope pleaded with all leaders to realize that if missiles were fired, from anywhere, untold millions would die. Millions more would suffer unbearably. Life would be back in the Stone Age.

Someone in Moscow heard the pope. Russian newspapers, all tightly controlled by the government, published the pope’s speech — the first time ever that any Russian medium reported a papal comment. Most importantly, the Russians declared that they were bringing the missiles home.

Kennedy never forgot. St. John XXIII died the following June. Historically, the United States officially ignored papal events, but Kennedy announced that he was sending Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to represent the American people at the pope’s funeral. Protestant leaders were outraged that this country’s second highest official publicly would honor a deceased head of the Catholic Church! Politicians warned Kennedy that bigots would remember it when he ran again.

Kennedy stood his ground. Johnson went to the funeral. Kennedy defended Johnson’s presence at the funeral by noting that many Americans were Catholics who considered the late pontiff a great spokesman for peace, justice and compassion, and an inspiration, but people close to Kennedy knew that the president thought that John XXIII saved civilization.

The pope gave credit to Almighty God.

Following John XXIII was Pope St. Paul VI, who created his own reputation for championing the downtrodden and was acknowledged worldwide as an extraordinarily wise advocate for peace and justice. When he died in 1978, President Jimmy Carter, a Baptist, sent his wife, First Lady Rosalynn Carter, to represent the American people at the papal funeral. Nobody complained.

Msgr. Owen F. Campion is OSV’s chaplain.