It’s time we admit it.

The Catholic Church … well, there’s divisions in the ranks — the highest ranks, too. Previously hidden under corporate smiles and corporate speak, a see-through solidarity that didn’t fool anybody anyway, now the fight has broken out between bishops.

All of it, of course, profitably retweeted, countlessly liked by partisans of the conflict, Twitter’s wars have now drawn bishops into its fray. There’s no use pretending. We read it, we hear it; we see what earlier we only assumed. A spectacle now is our Catholic Church in America.

None of this, though, should dishearten you, only those historically unalert. Bishops fighting is more central to the tradition than cramped institutional unity. From Paul and Peter to Clement’s first epistle; from Cyprian’s criticisms of Stephen to the entire fourth century; from Stephen VI’s “cadaver synod” to Avignon and beyond, episcopal combat is more norm than aberration. And, quite often, name-calling — calling one’s opponent a “new Judas,” things like that — was the least offensive thing about it. Most of Christian history, you must remember, we clergy were not gentlemen. In that regard, today’s fighting is quite traditional.

And there’s something good and bad to it, all this episcopal fighting — something fruitful and destructive. Fruitfully, such conflict is just the grist of tradition. As Alasdair MacIntyre taught, tradition is but an extended argument. Augustine talked about the “usefulness” of heretics; Newman, about the dogmatic value of controversy. Conflict is necessary to the discernment of truth. In that respect, bishops’ fighting might be, in reality, a sign of life, the undoing of sham institutionalism in favor of real tradition.

But, as I said, there’s something destructive about it, dangerous. Read, for instance, the end of Basil the Great’s “On the Holy Spirit,” where he likens the Church to a naval battle, in which, ruined by megalomaniacal leaders, everyone sinks. Read Clement’s warning: “Your disunity has led many astray.” Gregory Nazianzen, in his day, lamented how the Church was made a spectacle by such fighting. Spiritually a disaster, it only strengthened the devil: “The enemy laps up what we say,” he wrote. All of it poison the devil would one day spit back in Church’s face.

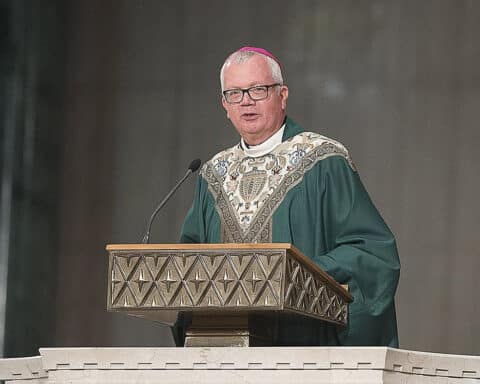

So, what to make of the conflict between the cardinal-archbishop of San Diego and the bishop of Springfield, Illinois? It’s best to be candid but not overdramatize it. Also, avoiding the quasi-scholastic murmuring of experts, the many canonists and credentialed theologians eager to explain it all, how can we put it simply? What does it mean?

It means we’re at a fork in the road. I know; I’ve seen it before. Allow me to speak personally. I’m a convert. Once an Episcopal priest, trained in England, Anglicanism was my spiritual nest. However, ecclesiology made me a Catholic: Irenaeus and Newman changed my mind. I didn’t escape Anglicanism, as is often said about people like me; rather, the beautiful truth of the Church enraptured me. That’s why I submitted to Rome, nothing else.

Which is why, in charity — calling no one names, accepting the goodwill of all — I need to raise my hand in brotherly warning to say this: What Cardinal McElroy is suggesting, it appears to me, is that we follow the path of the Episcopal Church, becoming more like Anglicans than Catholics. I’m not talking immediately about his progressive views but about his interpretation of the “culture of synodality,” which I fear too much displaces the magisterium’s lead role in seeking and safeguarding truth. His desire for inclusion, I share; his method, however, I’ve seen before, and it doesn’t work. Not genuinely inclusive, it reorders power only. Renewing nothing, it leads only to decline. Just ask the Episcopalians, the few who are left.

A serious charge, I know, and one I don’t have sufficient space to defend. And I don’t mean to insult either Episcopalians or Cardinal McElroy. But his words reek of what ruined a once beautiful Anglicanism, a sham inclusiveness, which as Cardinal Ratzinger observed, only led Anglicans into endless “chronic conflicts” from which it hardly ever escaped its integrity intact.

Make not these mistakes. We could indeed learn much from Anglicanism, but not this. I don’t fear inclusion, only the cardinal’s method. Because it doesn’t work; rather, it simply incites Machiavellian conflict and dilutes the Faith, rendering it first uncredible and then ultimately incredible. And it makes me fear that what Ronald Knox said of the Church of England almost a century ago could one day become true of Catholics: “You do not believe what your grandfathers believed, and you have no reason to hope that your grandsons will believe what you do.”

Which is why I don’t mind an episcopal fight or two. In fact, we may need a few more. Because of what’s at stake.

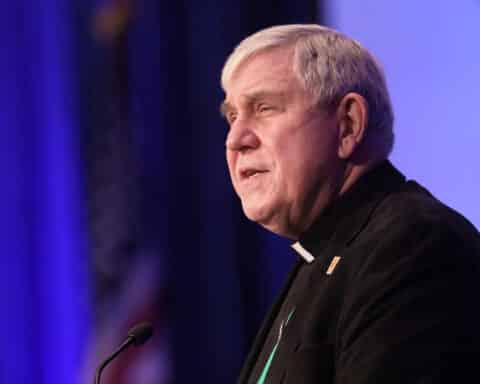

Father Joshua J. Whitfield is pastor of St. Rita Catholic Community in Dallas and author of “The Crisis of Bad Preaching” (Ave Maria Press, $17.95) and other books.