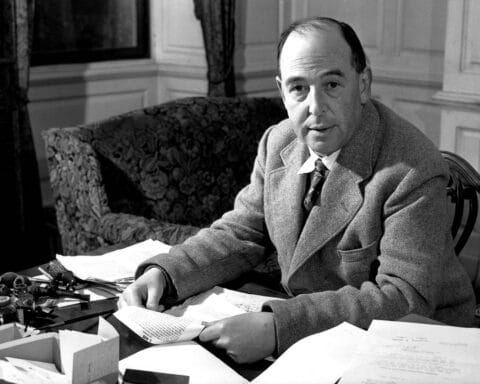

The last Sunday of the Church year is the great solemnity of Christ the King. This year, the day after the feast is the anniversary of the death of one of my favorite authors, C.S. Lewis. With that chronological coincidence in mind, I turn to Mr. Lewis to help illuminate some aspects of the feast that tend to bother or confuse Americans.

Christ the King is a feast a lot of Americans don’t particularly identify with. Historically we’re kind of anti-king. Today’s readings don’t help make the image more palatable — riding on clouds, receiving dominion and power, the Lord is king in splendor robed! These are the traditional images of a king with which so many today feel uncomfortable.

May I be bold enough to suggest that the folks who don’t like those images, who feel really uncomfortable with this whole imagery of king triumphant and power and hierarchy — those folks actually have it right.

Let me tell you a story — it’s a C.S. Lewis story, and it was the first one I ever read. I discovered it in fifth grade, and I thought it was about the most exciting thing I had ever read — and then I discovered there were seven books in the series!

What I “discovered” in fifth grade has since become common fare, and pretty much everybody knows the Chronicles of Narnia. The first book I read was the first in the Narnia series, “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.”

For those unfamiliar with the story, four English children during the Second World War, moved from London to a house in the country, discover that they can travel into a magical land by going through the back of a wardrobe. The land (which has talking animals) is frozen, under the spell of a wicked witch. But there are rumors in the land that the great lion, Aslan, will soon come and free the land and return it to the natural state that was present at the creation of this magic country.

Aslan does come, but the witch, with the use of lies and sweet candy — Turkish delight — has captured one of the children, Edmund, and is going to kill him. Aslan meets with the witch and offers a trade — his life for Edmund’s. They meet at a great stone table, ancient with traditions and stories of deep magic. Edmund is freed, and Aslan gives himself over to the power of the witch. She shaves off his mane, ties him, and kills him on the great stone table.

The word goes out and the land is desolate. But people notice that the snow is melting, flowers are starting to break through the snow, and eventually, of course, Aslan reappears, roars, the spell is broken, and the land is freed from the curse. It is a great story of faith and resurrection, and even as a child, I immediately realized the parallel between the story of Aslan and Narnia and the other story of Jesus Christ and our world.

The point, of course, is that the king — Aslan, the Lion — has the power, and he can only really use it when he gives it away. Think about that for a bit. Power does not consist in winning, or in beating people up, or intimidating them with how strong and mighty and rich and fancy you are. Power — real power, true power — God’s power — is something else. Loving. Serving. Being willing to trust in God rather than in muscles or in bullets or in — whatever.

That’s what the Gospel is about. Last summer when I was on retreat, I came across a line in the breviary. I know it had been there before. I just wasn’t ready to see it or hear it or understand it. That’s why we keep reading Scripture — not that “it” changes, but hopefully, we do. The line said, “Help us to overcome evil by good.”

Not by strength or by riches, or by programs or foundations or service projects or community action groups. By good. We begin with ourselves, and we work at becoming better. Becoming good. Being good. Living good lives, doing good things, being good people. Sounds really simple, doesn’t it. Not very sexy or glamorous or trendy. Nothing new there. Everywhere I turn there are new books and new programs and new philosophies, and the message is that all we have to do is sign up for this program or this philosophy and everything in our lives will be good. Most of us, most of the time, we know what it means to be good. We don’t need a degree program or a reference book or a panel discussion — we know what that means.

Be good.

When Jesus was brought before Pilate, it was Aslan at the stone table. He had the power, and he chose not to use it. His power came from being good — from trusting in God — from not buying in to someone else’s definition of power or strength or might or what it was to be a king. Surrendering to God brought victory, the victory over evil, and even more, the victory over death.

We are called to follow Christ — to empty ourselves, as he did so that there is nothing to get in the way of God. It is not the model of the world, the image that we see on television or in movies about what “success” means in our world. Surrender is not what we usually associate with kings or rulers or leaders. Yet the model is clear — we must surrender everything to God if we are to “win.”

Always be careful of people who want to set the definitions. This is what it is to be cool or trendy or popular. This is what it means to be successful. This is what it means to be happy. Those are not the definitions we find with Jesus Christ, so be very careful about letting someone else set the definitions.

We are called to be like Jesus Christ, this Christ who said he was called into the world to bear witness to the truth. If that means we should be kings — so be it. But we should be kings like Jesus Christ, not the other guys.

Father John R. Sheehan, SJ, is the chaplain of the University of Saint Francis in Fort Wayne, Indiana.