The early Christians experienced persecution for their faith, including martyrdom, first at the hands of the Jews and then at the hands of the Romans.

Some historians contend that the Church was born out of the persecutions and martyrdom of its first members. One could expand that contention by adding that the early Church actually thrived and grew out of such persecutions. Indeed, we often hear or read that quote from Tertullian, second century theologian and one of the Latin Church Fathers: “The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christians.”

What is a martyr?

A Christian martyr is someone who suffers death for their faith; that is, they are willing to die rather than deny Jesus Christ or his Gospel. The official teaching of the Church was espoused by Pope Benedict XIV (r. 1740-58), who defined martyrdom as “the voluntary enduring or tolerating of death on account of the Faith of Christ or another act of virtue in reference to God.”

Over 200 years later, Pope Benedict XVI (r. 2005-13), in a 2006 letter to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, confirmed the teaching of Benedict XIV, clarifying: “It is of course necessary to find irrefutable proof of readiness for martyrdom, such as an outpouring of blood and its acceptance by the victim. It is likewise necessary, directly or indirectly but always in a morally certain way, to ascertain the ‘odium Fidei‘ [hatred of the Faith] of the persecutor.”

We certainly understand a person giving up his or her life for a family member or even a friend. But thousands of people have been martyred for someone they have never met in the flesh, Jesus Christ. What is the magnetism of this man from Nazareth? What is so special about this itinerant preacher who was born in a stable? Those known as his apostles were persecuted and eventually martyred because of their love for him. But they weren’t the only early Christians who experienced ill treatment, even death.

| Martyrdom and the Catechism of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

“Martyrdom is the supreme witness given to the truth of the faith: it means bearing witness even unto death. The martyr bears witness to Christ who died and rose, to whom he is united by charity. He bears witness to the truth of the faith and of Christian doctrine. He endures death through an act of fortitude.”

— No. 2473

|

| MIRACLES OF THE MARTYRS |

|---|

|

St. Longinus (d. first century)

It is said that when the centurion Longinus threw his spear into Christ’s side at the Crucifixion, some of the blood and water from Jesus’ wound fell into Longinus’ eyes, healing him of his cataracts and leading to his conversion. One story says that when he was arrested for his faith, the governor commanded that they tear out his teeth and cut off his tongue, but Longinus continued to speak clearly. When Longinus destroyed several idols, the demons living within them blinded the governor, and his sight only returned after Longinus was beheaded and some of his blood got in the governor’s eyes. Another legend says that Longinus gave a large dinner for the soldiers seeking the faithful centurion — who did not know his identity — and then proceeded to turn himself in. Longinus’ spear is one of the many relics of Christ, and it can be found in St. Peter’s Basilica. The Virgin Martyrs

The early lives of the Virgin Martyrs follow similar narratives: These young women refused (or at least tried to refuse) to get married, and instead consecrated themselves to Christ. Some were from rich, noble families, and in one way or another, their rejection of the cultural norm of marriage and their staunch beliefs in Christianity led to their deaths: Cecelia (d. 2nd-3rd century) was unsuccessfully beheaded, dying three days later. Agatha (d. 251) was sent to a brothel before being tortured, including having her breasts cut off. Lucy’s (d. 304) eyes were plucked out before she was killed by the sword. Anastasia (d. 304) was either beheaded or burned alive. And Agnes (d. 304) was dragged naked through the streets, but her hair is said to have grown to cover her body; she was then beheaded. |

Persecution by the Jews

Jewish persecutions of Jesus’ followers began almost immediately after his ascension back to the Father. Jesus repeatedly had told his apostles that he would not leave them alone, and 10 days after ascending to heaven, he sent the Holy Spirit upon the apostles and the believers in Jerusalem to remain with mankind forever. Having deserted Jesus during his passion (except for St. John) the apostles’ faith had been shaken. But now that faith was renewed; they were strengthened by seeing and being with the resurrected Christ. Any uncertainty or fear was further extinguished by the flames and wind of the Holy Spirit, and the apostles were now fortified with the gifts of the Spirit and were ready to spread the Good News. In their newfound joy, each one came to understand the persecution that was before them. Jesus had said, “If the world hates you, realize that it hated me first” (Jn 15:18). They relished the idea of being able to imitate the sufferings of their savior.

According to the New Testament Book of Acts, on the day of Pentecost, Peter made an impassioned speech to the “Jews of every nation.” In the speech, he accused the Jewish leadership of murdering Jesus: “This man [Jesus], delivered up by the set plan and foreknowledge of God, you killed, using lawless men to crucify him. But God raised him up, releasing him from the throes of death, because it was impossible for him to be held by it” (2:23-24). Those listening “were cut to the heart” (2:37).

The apostles would continue to remind the Jewish leadership that they had caused the murder of Jesus. The Jews, especially members of the high court, the Sanhedrin, didn’t want to hear this; they didn’t want to be publicly associated with the murder. Also, the Sanhedrin were concerned, as they realized the impact the apostles were having on the common Jew. Guided by the Apostles, the followers of Christ took care of one another, shared what they had and worshipped one God. Some even performed miracles. Most impressive to anyone looking in was the fact that Christians loved everyone.

Given the charisma of the Christians, the high court repeatedly confronted the apostles, at first only ordering them not to preach the message of Jesus. The apostles ignored the warning and continued to perform “signs and wonders,” caring for the sick and needy, and increasing their number of followers. Soon the Sanhedrin wondered, “What are we to do with these men?” (Acts 4:16). They had the apostles thrown in jail, but an angel of the Lord helped them escape. Stunned, the high court sent soldiers to recapture them and, along with telling them to stop preaching, had the apostles flogged. The only impact these acts had on the apostles was to make them more dedicated to spreading the words of Christ; in fact they rejoiced over the fact they had suffered for Jesus (cf. Acts 5:17-42)

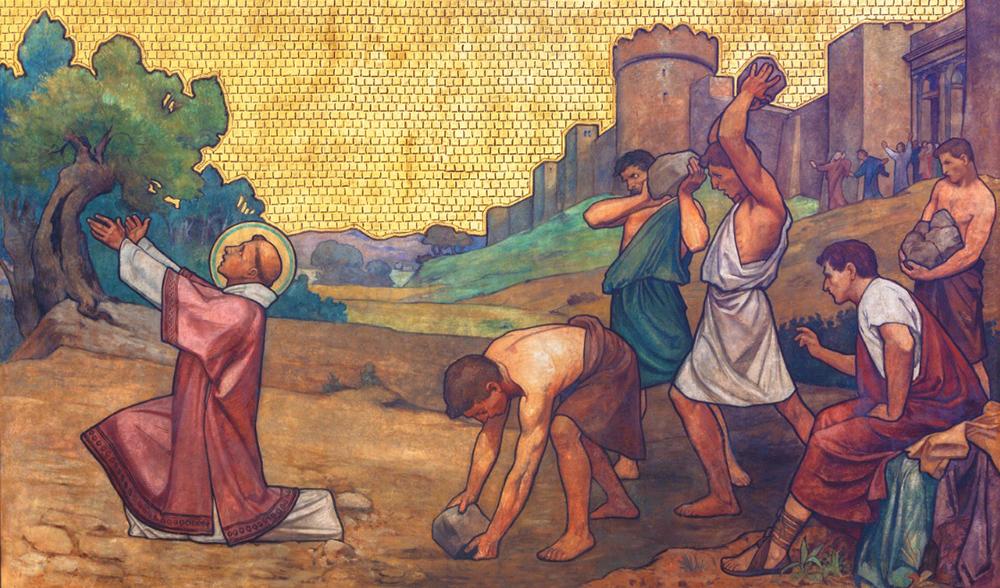

Eventually, the situation came to a head with St. Stephen, who was one of the first named as an assistant to the apostles. He was “working great wonders and signs among the people” (Acts 6:8) and zealously spreading the word of God. The Jews accused him of blasphemy against Moses. Stephen would not back down or be intimidated, and in a speech to the Sanhedrin he told them that in the history of Israel, the Jewish people continuously had rejected God’s chosen leaders. He called the Jews “stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears,” saying they had murdered the righteous one and did not observe the law that was “transmitted by angels” (Acts 7:51-53). Upset, the council members turned to violence. When he said, “‘Behold, I see the heavens opened and the son of man standing at the right hand of God’ … they covered their ears and rushed upon him together. They threw him out of the city and began to stone him” (Acts 7:55-58). As he was being unmercifully subjected to the stones and rocks, Stephen, in the manner of Jesus from the cross, said, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them …” (Acts 7:60). The Scriptures tell us that Saul (St. Paul) was there giving his ascent to the stoning as he guarded the cloaks of the murderers.

All the apostles were susceptible to Jewish persecution, as they were seeking to convert both Jews and gentiles. St. Paul, who had converted from being a zealous Jew seeking to persecute Christians to being an evangelist for Christ, would suffer greatly at the hands of the Jews. Not only because of the message he was spreading, but because he had turned against them. He was chastised, jailed several times, whipped, run out of town, shipwrecked and once left for dead after being stoned. Among the Twelve, only James (the Greater) was actually killed by the Jews: “About that time King Herod laid hands upon some members of the church to harm them. He had James, the brother of John, killed by the sword” (Acts 12:1-2). The king was Herod Agrippa of Judea (r. 41-44), who, upon seeing the positive reaction by the Jews to James’ death, arrested Peter and planned to kill him, but a miracle foiled his plan.

King Herod Agrippa had Peter secured by four squads of soldiers and imprisoned with chains. During the night an angel came and brought him out of the prison. This rescue is similar to that of the apostles earlier, as well as that of Paul and Silas in Philippi (Acts 16:16-40). In each case, God came to the aid of the apostles. The next day, when Herod couldn’t put Peter to the sword, he angrily had the soldiers killed who had been charged with securing Peter (Acts 12:6-19). Certainly, many Jews, stirred up by the Pharisees, hated the followers of Christ.

Persecution and even martyrdom came to be expected by those calling themselves Christians. Those early followers of Jesus understood that suffering and witnessing for the Faith couldn’t be separated.

|

“From the earliest times, then, some Christians have been called upon — and some will always be called upon — to give the supreme testimony of this love to all men, but especially to persecutors. The Church, then, considers martyrdom as an exceptional gift and as the fullest proof of love. By martyrdom a disciple is transformed into an image of his Master by freely accepting death for the salvation of the world — as well as his conformity to Christ in the shedding of his blood. Though few are presented such an opportunity, nevertheless all must be prepared to confess Christ before men. They must be prepared to make this profession of faith even in the midst of persecutions, which will never be lacking to the Church, in following the way of the cross.”

— Lumen Gentium, No. 42 |

| MIRACLES OF THE MARTYRS |

|---|

|

Sts. Perpetua and Felicity (d. 203)

No one was exempt from persecution if they were a Christian. Among the earliest surviving writings from the Church are the records of Perpetua, a woman from a noble family, and her slave, Felicity. Perpetua had recently had a baby, and Felicity was pregnant at the time of their trial. However, after she gave birth, Felicity was allowed to be executed with her fellow Christians. After being whipped and trampled by a wild beast, they were killed by the sword. However, Perpetua’s executioner missed, cutting between her bones and failing to kill her on the first stroke. Legend says that she guided the man’s sword back to her neck to help with the final blow. St. Quiteria (d. 2nd century)

The tame version of Quiteria’s story is that she was beheaded after she refused her father’s wishes that she marry and denounce Christianity. Another version is nothing less than bizarre. Not only was she the youngest of nonuplet sisters — that’s nine girls born at once — but she and her sisters were rejected by their mother, a noble woman who ordered the nurse to drown them. However, the nurse was a Christian woman, and she brought the girls to a village where they were raised in the Faith. As the girls got older, Quiteria and her sisters formed a sisterly warrior gang to break Christians out of prison and crush Roman idols in the process. When they were arrested, their father, who was a local leader, somehow recognized them as his daughters and tried to convince them to marry pagan men. Instead, they broke out of jail (possibly with the help of an angel) and waged guerilla warfare against the local government until they were recaptured and eventually beheaded. It is said that Quiteria’s body and dismembered head were thrown into the sea, but she walked out from the water and went to the Church of the Virgin Mary, carrying her head in her hands. She, along with two of her sisters, Marina and Liberata, are revered as saints. |

Roman persecution of Christians

Initially, the Romans tolerated the Christians; they considered them as part of Judaism. A Roman governor’s chief responsibilities were to maintain order and collect taxes. The governor didn’t much care about the Christians as long as they did not act against Rome and paid their taxes. This situation changed with Emperor Nero (r. 54-68). In A.D. 64, much of Rome was burned to the ground. Some Roman citizens believed Nero started the fire for his own amusement; others believed that he wanted to build a new Rome and a palace for himself. In any case, Nero was suspected of the act. In order to divert accusations from himself, Nero blamed the Christians who had a community in Rome. Many Christians were rounded up, arrested and tortured until they falsely accused others of setting the fire, who were in turn rounded up and tortured. Some of the accused were sent to fight the beast in the arena; some had their heads chopped off; others became human torches to light up the night.

Blaming Christians was an easy sell, as many Romans saw them as a secretive, superstitious group, worshipping only one God and carrying out orgies and committing acts of cannibalism. Eventually, Nero included Peter and Paul in those arrested. During Nero’s reign, Peter suffered martyrdom by being crucified upside down, and Paul was beheaded. Despite these atrocities, Nero issued no universal edict about Christians, but more and more governors in the Roman occupied areas began to treat Christians with increased suspicion. For the next 247 years, persecution of Christians was sporadic, depending on the emperor and the time.

In 112, a governor named Pliny in modern-day Turkey sent Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117) an inquiry on how to deal with the Christians in his area. Pliny had executed some Christians, saying, “For I was persuaded, whatever the nature of their opinions might be, a contumacious [stubbornness] and inflexible obstinacy certainly deserved correction.” Pliny addressed certain of the others arrested, who claimed to no longer be Christians and were willing to pray to the Roman gods, “and offered religious rites with wine and incense before your statue … and even reviled the name of Christ.” The governor wanted guidance on how to deal with this last group. He also mentioned that names of individuals alleged to be Christians had surfaced through anonymous sources. Trajan’s response indicated there were no specific rules but Pliny had done the right thing. Trajan wrote, “Do not go out of your way to look for them [Christians].” He went on, saying that if someone is accused of being a Christian, he or she should be punished unless they deny that “he is a Christian and make it evident that he is not, by invoking our gods, let him be pardoned upon his repentance.” Trajan added: “Anonymous information ought not to be received in any sort of prosecution. It is introducing a very dangerous precedent, and is quite foreign to the spirit of our age” (“Letters and Treatises of Cicero and Pliny”).

This exchange of letters is evidence that Roman persecution of Christians was not necessarily constant; that is, in the early second century Christians were not being hunted down. At the same time, the content of the letters indicate that Christians were considered a criminal element. Any of the Christians of that era would have reveled in Pliny’s comment that they were stubborn, possessing inflexible obstinacy in defending their faith and their Lord, Jesus Christ.

While no widespread, continuous acts of persecution took place, the era was not without violence against Christians. Among those martyred during the second century was an early Christian philosopher named Justin. Around A.D. 165 he and other Christians were brought before the Roman prefect, Rusticus. They were threatened and coerced to profess faith to the Roman gods and to the emperor. Justin refused. Rusticus told him to obey or “be tortured without mercy.” Justin said: “‘We hope to suffer torment for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ, and so to be saved. For this will bring us salvation and confidence as we stand before the more terrible and universal judgement-seat of our Lord and Savior.’ … The other martyrs also said: ‘Do what you will. We are Christians; we do not offer sacrifice to idols.’ … They were beheaded, and so fulfilled their witness of martyrdom in confessing their faith in their Savior.”

In his work “Apology,” written in A.D. 197, Tertullian claimed that the Romans blamed the Christians for everything: “They [the Romans] consider the Christians to be the cause of every public disaster and of every misfortune which has befallen the people from the earliest times. If the Tiber rises to the city walls, if the Nile does not rise to the fields, if the weather continues without change, if there is an earthquake, if famine, if pestilence, immediately, ‘Christians to the lions!'”

Beginning around A.D. 249, the attitude of the Romans toward Christians changed for the worse. Emperor Decius (r. 249-51), in an effort to strengthen and consolidate his rule over the empire, required everyone living under Roman authority to acknowledge, even make a sacrifice to, the Roman gods and the Roman emperor. This acknowledgement had to take place in public before a Roman magistrate. It could be done by burning incense before an image of Decius or one of the pagan gods. Saying, “Caesar is god” was another way of showing allegiance to Rome. The individual citizen would then be issued a certificate; those who didn’t comply would be persecuted. Numerous historians believe that Decius saw the growth of Christianity as a threat to Rome and he blamed the Christians for most anything that had an impact on the empire, confirming what Tertullian had written about earlier. Although the edict of Decius was short-lived, worse situations for the followers of Christ were coming.

It was Emperor Diocletian who instituted the most far-ranging, severest persecutions on the Christians. His reign, from 284-305, witnessed an increase in Christians being martyred. Some historians claim numbers of over 3,000 martyrs by the early fourth century. Like Decius before him, Diocletian believed that Christianity was a threat that had to be dealt with. Although there had been no organized effort to overthrow Rome, the emperor concluded that he either had to embrace Christianity, or crush it. The threat against paganism, against the Roman culture, was too great and Diocletian chose to seek out and suppress Christianity.

At first, Diocletian directed the destruction of churches, the sacred books and the sacred vessels used in Christian worship services. Bishops and priests were jailed and tortured until they denied Christ and gave honor to Caesar. Those who didn’t obey became martyrs. Later, Diocletian reinstituted or enforced the early edicts that every person living in Roman-occupied areas had to make a public sacrifice to the Roman gods and the emperor. Imprisonment, torture and murder became commonplace among those who were unwilling to comply with the edict. While this was the time of awful murders, hangings, beheadings and people being drawn and quartered, it was also the time of increased numbers of people joining the Christian faith. The martyrs, the thousands who were persecuted from every walk of life, gave witness to the Gospel message of Jesus and caused more and more people to take notice. Eventually, in 311, Emperor Galerius halted the persecutions. However, this act did not end the persecution of Christians that continues today.

| MIRACLES OF THE MARTYRS |

|---|

|

St. Lawrence (d. 258)

When Lawrence, a deacon, heard that Emperor Valerian was commandeering all of the Church’s property, he began to give away the money and treasures of the Church to the poor. The emperor heard the news and ordered Lawrence to bring to him all the Church’s treasures, gold and silver. After three days, Lawrence produced an unexpected surprise: the poor, who are the true treasures of the Church. In his rage, Valerian ordered that Lawrence be burned alive. Tradition recalls the saint’s humor even during his martyrdom, as he said, “Turn me over, I’m done on this side.” St. Sebastian (d. 288)

Serving in the Roman Army under Emperor Diocletian, Sebastian used his position to help persecuted Christians. He even converted parents of the imprisoned and other important individuals to Christianity. Once Dioceletian discovered Sebastian’s disloyalty, he ordered the soldier’s body to be used as target practice. The archers left his body in the field, believing he was dead, but Sebastian was discovered and nursed back to health by Irene of Rome. Upon recovery, he confronted the emperor, who once again ordered his execution — this time by being beaten to death and thrown into a sewer. |

The Lapsed

One problem for the growing Christian Church came out of the Roman requirement that everyone give allegiance to the Roman emperor and Roman gods. While many Christians were willing to go to jail and die rather than reject Jesus, some Christians gave their allegiance to Rome. When the serious persecutions subsided, which they did for years at a time, many of those who had honored Caesar wanted to come back and be recognized once again as Christians. Leaders of the Church had strong, differing opinions on how these people, known as the “Lapsed” or “Lapsi,” should be handled. They had committed the mortal sin of apostasy and thus they had to at least make a confession and accomplish a penance. One group led by Antipope Novation (r. 251-58) was against their return at all, claiming the Church did not have authority to forgive such a mortal sin. Pope Cornelius (r. 251-53), took an opposite view, that the Church could forgive any sin and should, like Christ, be merciful to the sinner. He did insist on penance from each sinner, and the kind and length of the penance was based on the individual who had lapsed. This mid-third-century issue would lead to the Church dogma that in the Sacrament of Penance, through the priest acting in persona Christi, any sin can be forgiven.

D. D. Emmons writes from Pennsylvania.

| Martyrs are more than history |

|---|

|

Early in his pontificate, on May 12, 2013, Pope Francis canonized 800 Italian martyrs — St. Antonio Primaldo and his companions, who are known as the Martyrs of Otranto. The city was seized by Ottoman forces in the 1400s, and rather than renounce Christ and convert to Islam, they accepted death. This is one of the largest groups of martyrs to be recognized as saints.

However, martyrs are not relegated to the distant past. As Pope St. John Paul II said in a homily commemorating the witnesses of martyrs throughout the 20th century, “The experience of the martyrs and the witnesses to the faith is not a characteristic only of the Church’s beginnings but marks every epoch of her history” (No. 2). He even established a Commission for the New Martyrs of the Great Jubilee in 2000, which researched and catalogued those who had died for the Faith throughout the 20th century. The results: The “20th century has produced double the number of Christian martyrs [than] all the previous 19 centuries put together.” Modern martyrs include the witnesses of two native-born Americans: Christian Brother James Miller of Wisconsin, who was declared a martyr on Nov. 7, 2018, and Father Stanley Rother of Oklahoma, who was beatified in 2017. Both were martyred while serving in Guatemala in the 1980s, about seven months apart. |