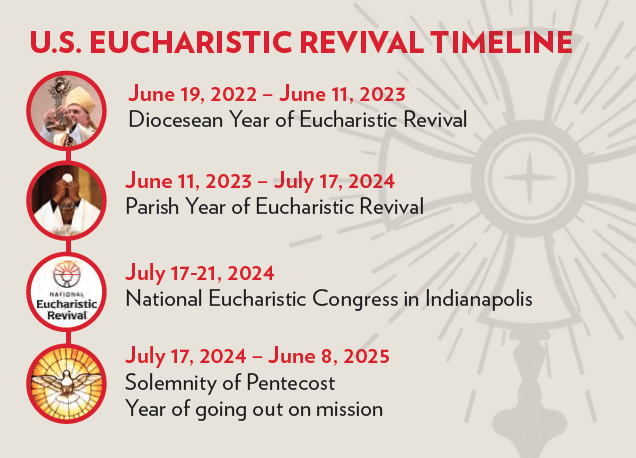

The 2023 celebration of the solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ (Corpus Christi Sunday) takes on added meaning as it marks approximately one year of the three-year National Eucharistic Revival. Launched last year by the U.S. bishops on Corpus Christi (which was celebrated on June 19), the revival is meant to cultivate in the heart of Catholics a deeper love for Christ physically present in the Eucharist, and to inspire active Catholics to share this love with others. And what better day to renew our commitment than on the day we honor the body and blood of Christ, which this year is Sunday, June 11. As we prepare for this great feast, let’s review some of the traditions and laws regarding the most holy Eucharist, as well as the history of the solemnity.

The Eucharist

Sacred Scripture identifies the Eucharist as the bread from heaven. We find this bread in the manna God feeds the Israelites when they were wandering in the wilderness. Manna, (meaning in Hebrew, “what is this?”) is described in the Book of Exodus (16:4-31): “The Lord said to Moses: I am going to rain down bread from heaven for you. … and when the layer of dew evaporated, fine flakes were on the surface of the wilderness, fine flakes like hoarfrost on the ground. On seeing it, the Israelites asked one another, ‘What is this?’ But Moses told them, ‘It is the bread which the Lord has given you to eat.’ … The house of Israel named this food manna. It was like coriander seed, white, and it tasted like wafers made with honey.”

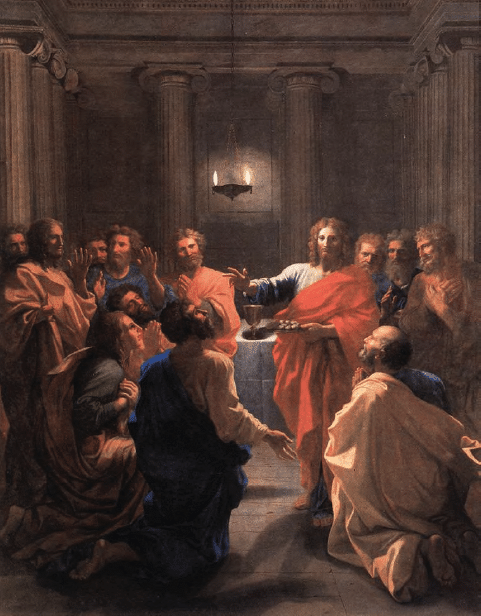

In the Gospel according to St. John (6:22-59), Jesus explains that he is the bread from heaven, he is the manna. “Your ancestors ate the manna in the desert, but they died; this is the bread that comes down from heaven so that one may eat it and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven.” Then he said, repeatedly, “unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, you do not have life within you.” These words were confusing, “this saying is hard,” and some followers turned away from Jesus. His apostles, even though they too were uncertain, did not leave and a year later during their final meal with Jesus, they grew to understand what he was saying.

At the Last Supper, Jesus took the unleavened bread, broke it and changed it into his own body, saying, “This is my body.” Now the apostles’ eyes were opened to what he meant earlier when he said that he is the living bread, bread from heaven. During this last meal with his apostles, Jesus miraculously changed the bread and wine into his body and blood and gave it to them. The Church holds that Jesus instituted the Eucharist at the Last Supper. During this meal, he also instituted the priesthood; our holy priests have continued for the last two thousand years to consecrate the bread and give it to the faithful.

Early in Church history, Catholic Christians regarded the Eucharist as food from Christ. In the second century, St. Justin Martyr explained: “This food we call the Eucharist, of whom no one is allowed to partake except one who believes that the things we teach are true, and has received the washing for forgiveness of sins and for rebirth, and who lives as Christ handed down to us. For we do not receive these things as common bread or common drink; but as Jesus Christ our Savior being incarnated by God’s word took flesh and blood for our salvation” (“The First Apology,” Chapter 66). Today, we continue such high esteem and love of the Eucharist, being careful how the precious body and blood are handled, fasting before holy Communion, making a gesture of adoration when receiving, politely denying this food from heaven to those who do not yet believe as we do, securing the consecrated host in our tabernacles, and signifying the Real Presence by an eternal flame.

Receiving holy Communion

At the Council of Trent in 1551, the bishops proclaimed: “In the Blessed Sacrament of the Eucharist after the consecration of the bread and wine, our Lord Jesus Christ, true God and true man, is truly, really, and substantially contained under the appearances of those perceptible realities.” Those of us approaching this most august mystery must be in a state of grace and follow all the norms of the Church.

When receiving Communion, we should consider the adoration of the Magi who “prostrated themselves and did Him homage” (Mt 2:11) or in the manner of Peter who “fell at the knees of Jesus” (Lk 5:8). The Book of Revelation reveals about adoring Jesus: “All the angels stood around the throne and around the elders and the four living creatures. They prostrated themselves before the throne, worshiped God, and exclaimed: ‘Amen. Blessing and glory, wisdom and thanksgiving, honor, power, and might be to our God forever and ever. Amen'” (7:11-12). A gesture that demonstrates reverence, humbleness and adoration are ways we express our love of the Eucharist. If we receive holy Communion while standing, then we adore Jesus by bowing our head when the minister raises the sacred host before us. St. Augustine wrote, “Nobody eats this flesh without previously adoring it.”

The way we conduct ourselves, our dress, our acts of adoration in his royal court reflect our love for the King of kings.

In the universal Roman Church, the normal method to receive holy Communion is while kneeling and the Eucharist placed on our tongue. In the United States, the norm, with Vatican permission, is to receive while standing and in the hand. This U.S. norm does not exclude receiving in the mouth (on the tongue) while standing or kneeling. Many Church leaders have and continue to encourage receiving on the tongue, which was the universal method for centuries. Receiving the Eucharist on the tongue, they argue, negates possible accidents like the host or separated fragments falling to the ground. Also, the recipient can’t carry the host back to the pew or outside the church, which has happened, and there is no danger of unclean hands touching the body and blood of Christ.

Before receiving this gift of holy Communion, we are encouraged to do an examination of conscience to ensure we are in a state of grace. We are also required to fast for at least one hour in advance, during which we are allowed only water and medicine. Some people believe coffee and tea are OK during the fast, but not so. The Code of Canon Law reads, “A person who is to receive the Most Holy Sacrament is to abstain for at least one hour before holy Communion from any food and drink, except for water and medicine” (Canon 919).

This Eucharistic Revival is a time for U.S. Catholics to examine the way we respect and ways we fail to respect the body and blood of Christ. Coming before the Blessed Sacrament is meant to be a sacred time, in a sacred place, in sacred silence. The Catechism tells us that “bodily demeanor (gestures, and clothing) ought to convey the respect, solemnity, and joy of this moment when Christ becomes our guest” (No. 1387). Simply, the way we conduct ourselves, our dress, our acts of adoration in his royal court reflect our love for the King of kings.

| Prayer after holy Communion |

|---|

|

Following receipt of holy Communion, humbly and weak, kneeling back in our pew, we can offer up our words of thanksgiving for this miracle in which we have just participated; this is a special time to relish. Here is a prayer from Thomas à Kempis in his book “The Imitation of Christ”: “To You, O Lord, the Father of mercy, I raise my eyes, and in You alone, my God, I put my trust. Bless and sanctify my soul with Your heavenly benediction; may it become a holy place where you may dwell-the place of Your eternal glory. Let nothing be found in this temple that may offend the eyes of Your Divine Mercy. Look down upon Your poor servant, Lord, exiled in the land of the shadow of death, and according to the greatness of Your goodness and Your manifold mercies, graciously hear my prayer. Defend and preserve my soul amid the many dangers of this corruptible life, and direct me by your grace along the path of peace, to the land of everlasting light. Amen.” |

St. Josemaria Escriva wrote about preparing for Communion: “When I was a child, frequent Communion was still not a widespread practice. I remember how people used to prepare to go to Communion. Everything had to be just right, body, soul: the best clothes, hair well-combed — even physical cleanliness was important — maybe even a few drops of cologne. … These were manifestations of love, full of finesse and refinement, on the part of manly souls who knew how to repay Love with love.”

The gift of Eucharistic adoration

“You have given them bread from Heaven,” the priest says during the benediction of the Eucharist.

As Catholics, we can worship the real presence of Jesus whether he is hidden in the tabernacle or exposed on the altar. Whenever a Roman Catholic enters a church, their eyes search for the glowing lamp identifying the Real Presence in the tabernacle. Canon 937 states: “Unless there is grave reason to the contrary, a church in which the Blessed Eucharist is reserved is to be open to the faithful for at least some hours every day, so that they can pray before the Blessed Sacrament.” The moments before and after Mass, before and after confession, or anytime the church is open are opportunities to spend before the tabernacle, giving thanks, telling Our Lord that we love him. Before Mass, we can forget the noise of the secular world and give our attention to Jesus, who we will shortly receive in holy Communion. Similarly, the time after Communion is an opportunity to carefully reflect on the Eucharist we just received; certainly it is not a time to leave the Mass.

Few periods in our life are more exquisite than those spent before the Blessed Sacrament, before our awesome God, exposed outside the tabernacle. Placed on our altars, most often in a monstrance, we come before a living person, Jesus, not before some passive object like the golden statue King Nebuchadnezzar had made (cf. Dan 3:1) or the calf melded together by the Israelites (cf. Ex 32: 3-4). During Eucharistic adoration, we can relate to a comment by a parishioner in St. John Vianney’s parish at Ars, France. When asked what he did sitting in the church all day, the parishioner responded: “I look at the good God, and he looks at me.” The parishioner knew that what he was looking at and adoring was not a symbol, not an image, but the living Lord, the Real Presence.

Few periods in our life are more exquisite than those spent before the Blessed Sacrament, before our awesome God, exposed outside the tabernacle.

Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament for extended periods can be traced back to the 14th century. Often the intent was to expose the Blessed Sacrament in times of famine, epidemics or threats of war. Records of a crisis in the 16th-century indicate that during the threat of an overwhelming invading army, St. Charles Borromeo, Bishop of Milan, Italy, encouraged people to come pray before the exposed Blessed Sacrament. The people responded and the invaders turned away. These times of exposition were often for 40 hours with many churches involved. Exposition would end in one church and, at the same time, begin in another. While every parish was once required to annually hold a 40-hour devotion, today Canon Law only recommends periods of expanded Eucharistic adoration: “It is recommended in these churches and oratories, there is to be each year a solemn exposition of the blessed Sacrament for an appropriate, even if not for a continuous time, so that the local community may more attentively meditate on and adore the eucharistic mystery” (Canon 942). Today many parishes have exposition of the Blessed Sacrament on a perpetual basis, that is, 24 hours a day, year around.

The history of Corpus Christi

The greatest of all our liturgical celebrations during Ordinary Time is the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ. Eight hundred years ago, Pope Urban IV (r. 1261-64) sought to establish, through his papal bull, Transiturus, what was then called the feast of Corpus Christi, a celebration of the Eucharist. Several events motivated Pope Urban.

In the 11th century, there were heretical groups like the Berengarians that denied or questioned the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist; they had a large number of followers, and it took some effort by the Church to turn this situation around. Early in the next century, many of the faithful believed in the Eucharist but concluded that they were not worthy to receive the body and blood of Christ. People in large numbers stopped going to holy Communion. Now this development has to be viewed in the context that in that era most people received Communion only two or three times a year; but not going at all alarmed the Church. At the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, the bishops mandated that every Catholic receive holy Communion at least once a year, during the Easter season: “All the faithful of either sex who have reached the age of discretion, must faithfully confess all their sins at least once a year to their own parish priest, carefully perform, as far as they are able, the penance which is imposed on them, and reverently receive the Sacrament of the Eucharist at Easter. … Otherwise, they are forbidden to enter the church, if they are alive, and to be deprived of burial by the Church, if they are dead.”

| Year One of the Eucharistic Revival |

|---|

The first year of the National Eucharistic Revival, which started on June 19, 2022, was focussed on the diocesan level. Diocesan staff, bishops and priests were invited to respond to the Lord’s personal invitation in the Eucharist and were equipped to share this love with the faithful. As the revival enters its second year with a focus on each parish, these diocesan staff, bishops and priests can begin cultivating the revival at each Catholic church through events, such as Eucharistic processions, 40-hours devotions, book studies on the Eucharist, and more, all leading up to the 2024 National Eucharistic Congress, which will be held in Indianapolis. Find out more at eucharisticrevival.org. |

At the same time, a strange cult developed among the faithful. Instead of consuming the body and blood of Christ, they wanted to look at it, a kind-of seeing or gazing adoration. Around 1220, the priest accompanied by a bell being rung, started elevating the consecrated host in the Mass. This act was largely in defiance to those claiming the Eucharist was not the body and blood of Christ. While not prompted by the Church, many in attendance would adore the host in the elevation and then go from church to church timing their arrival with the moment of elevation. In some places the laity offered the priest a stipend to extend the time of elevation.

While these circumstances caused concern among Church leaders as to how people regarded the Eucharist, two other events were the likely catalysts for the institution of a special Eucharistic feast day.

The first was the Eucharistic miracle at Bolsena, Italy, in 1263. Father Peter of Prague, who questioned that he could change bread and water into the body and blood of Christ, was celebrating Mass in the church of St. Christina and had just spoken the words of consecration, when the precious blood of Jesus spilled out of the host and onto the priest’s hand, the corporal and the altar cloth. Pope Urban IV was staying in nearby Orvieto, and Father Peter went to him explaining what had occurred. Pope Urban had the incident investigated and determined that it was a miracle.

The other event that influenced the pope was his personal knowledge of the visions of a nun in the Diocese of Liege, Belgium nearly 35 years earlier.

In the mid-13th century, St. Juliana, a nun in the Augustinian monastery near Liege, claimed she had repeated visions for 20 years during which she saw a full moon with a stripe on it. At one point in her visions a voice, which she believed was Jesus, explained that the full moon represented the Church and the stripe indicated that there was no feast or celebration honoring the Eucharist, even though there were hundreds of other celebrations. He wanted Juliana to pursue the establishment of a feast to honor the Eucharist. Juliana made her visions known to officials in the Liege diocese, and while some rejected what she said, Bishop Robert de Thorte realized the importance of such a celebration. Eventually, in 1246, Bishop de Thorte acted to institute a feast honoring the Eucharist inside his diocese, but he died within the year and there was little interest in pursuing a universal feast day. There was, however, another person in the diocese who recognized the merits of a Church-wide special devotion. That person was an archdeacon named James Panteleon, later Pope Urban IV.

In his 1264 papal bull, Transiturus, the pope wrote, “Therefore, in order to strengthen and exalt the True Faith, we have thought it just and reasonable to ordain that, besides the commemoration which the Church daily makes of this Holy Sacrament, a particular day, namely, on the fifth day of the week after the octave of Pentecost, on which day pious people will vie with each other to hasten in great crowds to our churches, where the clergy and laity will send forth their holy hymns of joy and praise. On this memorable day, faith shall triumph, hope be enhanced, charity will shine, piety shall exult, our temples shall re-echo with hymns of exultation and pure souls shall tremble with holy joy.” St. Thomas Aquinas was commissioned to write music for the celebration, and we still sing his hymns whenever there is exposition of the Blessed Sacrament. Pope Urban IV died in 1264, the same year his papal bull was written, and the feast of Corpus Christi did not achieve Church-wide acclaim until the reign of Pope John XXII (r. 1316-1334). Many countries celebrate the feast as a holy day of obligation on the Thursday after Holy Trinity Sunday; in the United States, it is held on the Sunday after the Solemnity of the Holy Trinity.

Minsk, Belarus. CNS photo/Vasily Fedosenko, Reuters

Processions and indulgences

While the feast of Corpus Christi was introduced into the Church as early as the 13th century, it was the next century before a procession was included as part of the celebration. Taking the Eucharist outside the church in a public procession likely began when the bread of life was taken to the sick. Reverencing the Eucharist in a procession on the feast of Corpus Christi began in the late 14th century when the Blessed Sacrament was carried through European villages and towns. Over the centuries, the processions became common in many countries and grew into elaborate spectacles that rivaled any honoring earthly monarchs.

Processions often began with children spreading rose buds on the ground in front of the marchers. Then came incense and candle bearers, the cross, bell ringers, the bishop (under a canopy, carrying a monstrance with the Blessed Sacrament), the clergy, civic leaders, members of local guilds, police and firemen, military units, a band(s), church groups, and, of course, the laity. Often these groups vied with each other for the best position, closest to the Blessed Sacrament. The route of the procession was onto city streets that were decked with flowers and banners. Only essential business transactions were accomplished during the time of the parade. There were typically four altars along the way where the procession would pause, everyone would kneel, Scripture was read and the people were blessed. The parades lasted for hours and ended with benediction, a blessing of the people with the monstrance containing the Blessed Sacrament. These solemn processions, then and now, publicly testify to our love for Jesus in the Eucharist.

“A procession through the streets is to be held as a public witness of veneration toward the Most Holy Eucharist, specially on the solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ.”

Today, Canon 944 encourages Eucharistic processions: “When it can be done in the judgment of the diocesan bishop, a procession through the streets is to be held as a public witness of veneration toward the Most Holy Eucharist, especially on the solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ.”

According to the USCCB’s “Manual of Indulgences,” “A Plenary Indulgence is granted to the faithful who devoutly … participate in a solemn Eucharistic procession, held inside or outside a church, of greatest importance on the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ” (No. 7.1.3).

This year, as the Eucharistic revival focuses on parish life, prioritize time in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. Participate in a Corpus Christi procession at your parish or a church nearby. And let the Lord speak to your heart, drawing you closer to his real presence in the Eucharist.