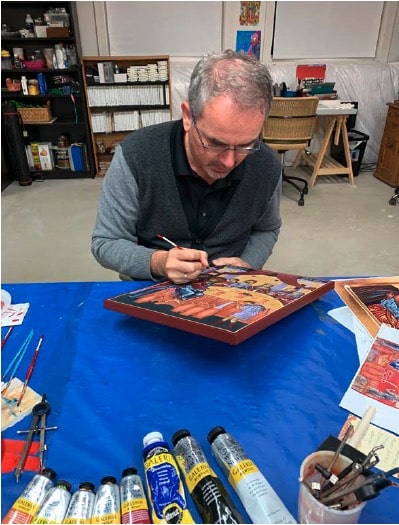

Father Marek Visnovsky was interested in drawing and painting when he was a child growing up in Czechoslovakia, and he was particularly intrigued with the icons in his church. It wasn’t until 2000 when he was in the seminary that he learned to write the ancient style of holy pictures.

“Once I got into them, when I later studied theology, the symbolism and spirituality were flabbergasting,” he said.

Father Visnovsky, who came to the United States in 2004, is pastor of Dormition Byzantine Catholic Church in Cleveland, under the Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Parma, Ohio, for the Ruthenians.

He has painted more than 700 icons that he displays in his home and in his church and other churches. He sometimes gives them as gifts or uses them to raise money for humanitarian causes. He is currently teaching classes to raise money for relief for the people of Ukraine.

“I believe that Christians have always tried to embrace iconography,” Father Visnovsky said. “In the first 300 years, when Christians were hiding in catacombs, they started painting images of those who gave their lives as witnesses for Christ. They painted the images on the walls, and they prayed to them. That’s how iconography started developing little by little.”

‘We are living icons’

Icons are “written,” not painted, and they follow the writing in Scriptures. For Christians who could not read or write, icons displayed in the church revealed those stories to them through pictures.

“The word of the Gospel is for the heart, and the icon is for the eye,” Father Visnovsky said.

Read more from our Spring Vocations Special Section here.

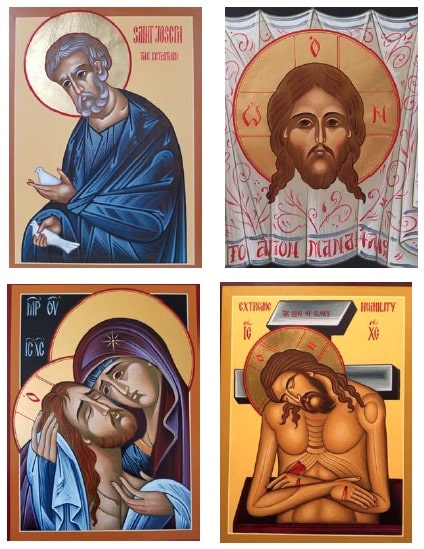

Icons are not just decorative or symbolic. They are described as windows into the next world and are used in meditation and prayer. They are stylized in a flat appearance with the subjects having elongated faces and small lips. Their eyes stare directly at the viewer, as if inviting them to a place of holiness. They are said to bridge the gap between the divine and humanity.

“Icons are still and quiet, yet they embrace us and bring us closer to God,” said Father Visnovsky, who noted that students in his classes experience the peace of being involved in something very sacred and holy.

“It’s a very slow pace, and there’s no rushing,” he said. “You come from a world where everything is rush, rush, rush and instant gratification. All of a sudden, you are sitting in front of a board with the image of Christ, or the image of the Mother of God, or the image of a particular saint. That puts you in a totally different perspective. All of a sudden, as you approach the icon as a human being, as a Christian, you see in the anthropologic character, the beauty and harmony of it. That’s what you want to be like as a human being. You don’t want to be distracted. You don’t want to be a mess. You want to be beautiful. When you are looking at an icon eschatologically, that reflects a world to come. Those particular saints are in the heavenly realm that you are foretasting.”

His students include people who are beginners, advanced and in between. They are Eastern and Roman rite Catholics, Orthodox and some other Christian denominations — even people who profess no faith at all.

“I like to encourage people to make an icon, but your life is like making an icon,” Father Visnovsky said. “There is the image that God gave us in his son, and we are created in God’s image, and God’s image is within you. We are the living icons. I am reminding myself as a priest that, for someone, you may be the only Bible they will read. The question is: Am I helping people to see God not by talking but by my example? I was created in God’s image. Do people see that image of Christ in me? Who do they see?”

‘Given to God’

Father John Bambrick, pastor of St. Aloysius Parish in Jackson, New Jersey, grew up in a Roman Catholic parish that had close ties to a Ruthenian Byzantine rite church and the Hungarian order, the Hermits of St. Paul.

“They had this little chapel, and there I was as a young kid, and I walked in, and I didn’t know if we were in heaven or on earth,” he said. “There were these beautiful icons covered in gold. They were wonderful, mysterious and marvelous.”

That’s where his interest in icons began.

“We think of icons today as being an Eastern art form, but you can actually trace back the beginning of iconography to the Romans in Egypt,” he said. “You can go to the oldest churches in Rome to see all those icons that were painted, or are mosaics, or were hammered into metal, or painted with egg tempera on plaster frescoes. This is an art form that is common in both East and West, but the West abandoned it after the split. Then there was a revival, and now you can see many icons in churches today.”

He also credits Pope St. Paul VI with building a bridge across the gap between the Western and Eastern churches.

Father Bambrick studied iconography under several prominent iconographers and has arranged for several workshops to be held in his parish.

There are specific traditions in creating icons, starting with linen representing the shroud being glued to a very white board that, he said, “creates the uncreated light of God.” Paints layered on can be colored with precious natural materials, like crushed lapis lazuli.

“It gets into really biblical themes. The most expensive thing, like frankincense, would be burned on the altar, completely destroyed and given to God,” Father Bambrick said. “In the same way, iconography takes very special natural materials, and these beautiful things are given to God.”

Maryann Gogniat Eidemiller writes from Pennsylvania.