Like Christmas and other Catholic holy days, Easter is often misunderstood and mis-celebrated. Either its origins are said to be based on pagan holidays (a myth we will bust), or we treat it as a day to binge after a season of fasting. So, to fully embrace Easter, let’s look at how the early Christians understood and celebrated the day of Christ’s resurrection.

First of all, they didn’t call it Easter

What was Easter like in the early Church? Well, to begin with, they didn’t call it “Easter” — that word would be meaningless to them. The early Christians believed that Jesus’ passion and resurrection were the central part of the whole story of God’s saving activity in the world. These events were not seen as a single, isolated moment in history, but part of the great trajectory of God’s providential interventions.

More specifically, the passion and resurrection of Jesus were understood to be a continuation and fulfillment of the events of the Passover and the Exodus. And not coincidentally, the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus happened at the time of the festival of Passover, so when the early Christians referred to the annual commemoration of Jesus’ passion and the celebration of his resurrection, they simply called it Passover. It’s just like the way that Pentecost continues to be named after a Hebrew festival, even though it is given new meaning in the Church as the celebration of the gift of the Holy Spirit. And so in the early Church, the feast day of the Resurrection of the Lord was simply called Passover, or some translation of that word, as it still is to this day in most languages of the world. This is where we get the word “Paschal” in the Paschal Mystery. That just means, “the Passover Mystery.”

So what about the English word “Easter”? Where did that come from? Near as we can figure, it comes from an Old German word for “dawn,” as in, facing toward the dawn — facing east.

So then where did the English word “Easter” come from? Before we can answer that, we have to bust a myth or two. The word “Easter” is not derived from a pagan fertility gods or anything like that. It used to be popular to say that Christianity had borrowed holidays from paganism, supposedly as a way to make it easier for people to transition from paganism into Christianity, and the two most famous examples of that were said to be Christmas and Easter. The myth goes like this: The dates for Christmas and Easter were originally pagan festivals, perhaps the winter solstice and spring equinox, or maybe Roman festivals like Saturnalia and Lupercalia. Then, the name for the one that comes in the spring (“Easter”) supposedly came from one of the pagan deities — a fertility goddess who represented “new life” after winter is over.

But when one actually studies the early Church, it’s very easy to see that all of this is nonsense. The early Christians would be horrified for anyone to think they had borrowed from paganism, and the apologetic documents from the early Church prove this point in how critical they were of paganism. As far as the dates go, the date for Christmas is exactly nine months after the feast of the Annunciation (the conception of Jesus), and although there was a lot of debate over the date of Easter in the early Church — a debate we don’t need to go into here — the debate itself proves that the date was not based on anything other than the date of Passover. The question was not when to celebrate the Resurrection but how to calculate the precise date relative to Passover. In any case, nothing pagan to see here.

So what about the English word “Easter”? Where did that come from? Near as we can figure, it comes from an Old German word for “dawn,” as in, facing toward the dawn — facing east. This is a bit of an oversimplification, but think of the way we can talk about a storm that’s heading in the northeastern direction, and call it a “nor’easter.” By the same logic, the day we face the dawn in anticipation of our own resurrection is called easter. At least that’s how it comes into English, translated from Old German. But it helps to remember that “Easter” is only a word used in English. Most other languages still call it something that is a version of the word for Passover. For example, in Italian, it’s Pasqua. If it were up to me, I would banish the word “Easter” from our vocabulary, and go back to calling it the Pasch, or Resurrection Day.

It was never just one day

Just as the Eucharist was never just a “remembering” of the passion of Christ, the Pasch was never just an “anniversary celebration” of his resurrection. The celebration of the Pasch every spring was a way to relive the events of that week in a way that brings them back around so that we can participate in them — just like the celebration of the Passover brought back the events of the Exodus for faithful Jews. “Past history made present mystery,” as they say.

In fact, in Hebrew theology, a recurrence of the Passover happens in providential ways at certain significant times throughout history. In the Rabbinic commentaries on the Torah, there is a poetic expansion on the Exodus that speaks of not one, but four Passovers — and all of them were said to take place on the same date in the Hebrew calendar: the 14th day of the month of Nisan, the same day as the Passover at the time of the Exodus. This poem on the Passover is called “The Poem of the Four Nights.”

The first Passover “night” is the creation of the universe, and in Hebrew thought there is a specific date given for creation — also the 14th day of Nisan. This concept of tracing God’s saving acts in history all the way back to creation is why we start with Genesis when we read the whole story of salvation from the Scriptures during the Easter vigil.

The celebration of the Pasch every spring was a way to relive the events of that week in a way that brings them back around so that we can participate in them — just like the celebration of the Passover brought back the events of the Exodus for faithful Jews.

The second Passover “night” is the Binding of Isaac, when Abraham was tested by God’s command to sacrifice his son (cf. Gn 22). The Church fathers all saw this event as a foreshadowing of the passion of Christ. Just as a ram caught in the thorns became the substitute for the son of Abraham, so Jesus was the Lamb in the crown of thorns who became the substitution for all of Abraham’s children — both his literal descendants, and his spiritual children. And yes, the Hebrew scholars believed that this event also took place on the 14th day of Nisan.

The third Passover night was exactly the one you’d think — the one associated with the Exodus, the main event remembered in the ongoing Jewish tradition of the Passover, which was always celebrated on the 14th day of Nisan.

Then the fourth Passover “night” was to be in the future, from the perspective of the Hebrews; this would be the messianic banquet at the “Day of the Lord.” Of course, they didn’t expect that the “Day of the Lord” would actually be two “days”: a first advent of the Messiah, and a later second coming, at which time the final revelation of the Kingdom of God would take place. We live in the time between these two “days.”

So we, as Christians, actually have five Passovers. The hope of the messianic banquet was partly fulfilled at the Last Supper, when Jesus instituted the Sacrament of the Eucharist. But then he said he would not drink from that cup again until the final consummation at the wedding banquet of the Lamb when the kingdom of God is fully revealed, after the final resurrection. (Jesus hinted at this in his parable of the wedding banquet in Matthew 22.)

There was also a certain way in which the early Christians treated Resurrection Day like the beginning of a new year, in the same sense that we might make New Year’s resolutions to improve ourselves and our habits. So the early Christians used Lent, and then the Pasch, to solidify ways in which they wanted to take their spiritual lives to the next level.

In a beautiful Paschal sermon preached by Pope St. Leo the Great in the fifth century, he encouraged the people to use the season to make real changes in their lives, and after Lent, not just go back to their old ways. So it could be said that a homily for Resurrection Day was a real call to conversion, for as St. Leo said, no one who is proud, or greedy, or who denies the reality of Christ’s divinity and his bodily resurrection, can properly celebrate his Resurrection Day. Here is an excerpt from St. Leo’s sermon (I’ve paraphrased it a bit to make it easier to understand in English):

“I want everyone to remember that you are a new creation in Christ, and in all seriousness, understand what this means — that by identifying with Jesus Christ in your baptism you have been adopted by God the Father. Therefore, do not let anything that God makes new in you slide back into the old ways. This is what Jesus meant when he said that no one who puts his hand to the plow looks backward — to do the work of plowing you need to keep your eyes on the row ahead of you. Don’t fall back into the old version of you, no matter how hard it is, or how weak you think you are — if you think you’re weak or not healthy enough — remember that being strong and healthy means following Jesus through death into resurrection. You did this in your baptism, back when it was easier. Now you need to keep following in the path of resurrection that Jesus set for you. Then no matter how slippery the path of life is, you won’t slide into the quicksand, but your feet will stay on solid ground. Keep all this in mind, my beloved, not only for this Paschal season, but all year round and all your life, for the sake of your sanctification.”

| WISDOM FROM THE EARLY CHURCH |

|---|

|

“Death trampled our Lord underfoot, but he in his turn treated death as a highroad for his own feet. He submitted to it, enduring it willingly, because by this means he would be able to destroy death in spite of itself.” “Death had its own way when our Lord went out from Jerusalem carrying his cross; but when by a loud cry from that cross he summoned the dead from the underworld, death was powerless to prevent it.” “The season before Easter signifies the troubles in which we live here and now, while the time after Easter which we are celebrating at present signifies the happiness that will be ours in the future. What we commemorate before Easter is what we experience in this life; what we celebrate after Easter points to something we do not yet possess. This is why we keep the first season with fasting and prayer; but now the fast is over and we devote the present season to praise. Such is the meaning of the Alleluia we sing.” “I command you: Awake, sleeper, I have not made you to be held a prisoner in the underworld. Arise from the dead; I am the life of the dead. Arise, O man, work of my hands, arise, you who were fashioned in my image. Rise, let us go hence; for you in me and I in you, together we are one undivided person.” |

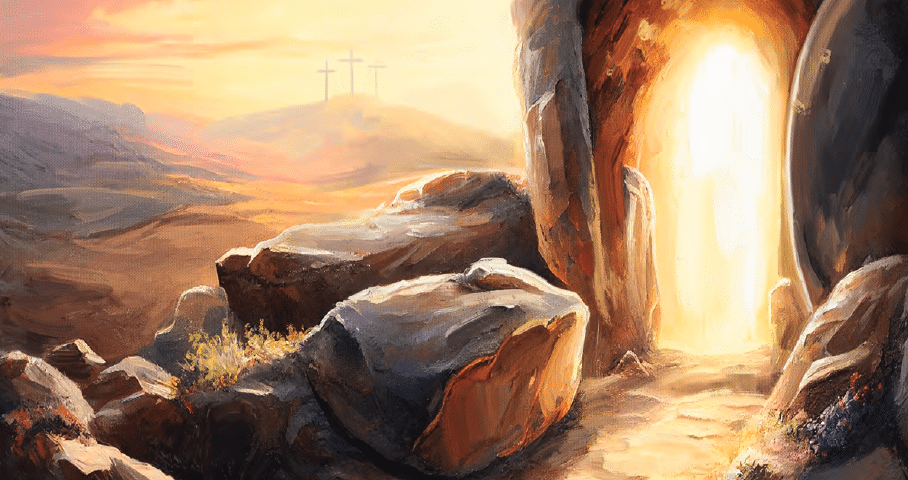

It’s more than the empty tomb

So on the one hand, the Pasch is not just one day, or even the anniversary of one day; it is a part of the recurring cycle of God’s past providential intervention in history, and the seasonal rhythm of our present participation in it.

On the other hand, it was also not just one feast day, as in “Easter Sunday.” For the early Christians, it was the whole Triduum. Technically the Triduum is from sundown on Holy Thursday to sundown on Resurrection Sunday. But in the early Church, not all Christians reckoned the day in the Jewish way, beginning at sundown, and so it wasn’t even limited to three days. For them, the Pasch extended from Jesus’ betrayal on Wednesday, through the Last Supper and Jesus’ unjust condemnation and all that he suffered up through his crucifixion, all the way to the end of Resurrection Day. That whole thing was considered a single “holiday/holy day” in which Christians participated in Christ’s passion and resurrection.

In fact, the big picture includes much more than Holy Week. For the Church fathers, salvation was not just about the crucifixion, or even just about the cross and the empty tomb. It was the whole of the Incarnation and life of Christ, starting with his conception at the Annunciation. And notice that we don’t usually wear little empty tombs around our necks, or make the “sign of the empty tomb.” The sign of the cross is the sign that encompasses every aspect of the Incarnation — Christ’s life, as much as his death, and of course his resurrection.

Methodius, in a Paschal homily from the early fourth century, wrote that the cross is both a trophy of victory and a ladder to heaven. And this is why we make the sign of the cross on our bodies. Back then, Christians made the sign of the cross on their foreheads, and the Church fathers taught that the forehead of a person was like the lintel of the doorway to his life — in other words, just as the sign in blood on the door lintels at the Exodus saved the children of Israel, making the sign of the cross on the “lintel” of our bodies is a sign of what saves us — But, again, what saves us is not only the death of Jesus, but his whole life. So the Resurrection was never disconnected from the Passion, and the Passion was never disconnected from the Incarnation. And this sign — just like the ashes we got at the beginning of Lent, which were in the shape of the cross — is a witness to the world that we “proclaim the death of the Lord until he comes” (1 Cor 11:26).

So what about this year?

What we call “Easter” is not only for the moment, as if it can just come and go like any other weekend. It’s about the past, present and future. It brings the past forward, connecting us in the present to the great interventions of God in history. Then the present becomes focused on the future, as we face the dawn, in an “easterly” direction, in the hope of the wedding banquet of the Lamb, that eternal family reunion.

And so as the Pasch approaches for this year, I want to encourage you to think about it — and try to observe it — the way the early Christians did. Here are a few suggestions:

1. Think of Resurrection Day as part of the grand trajectory of all of salvation history. Make a point to go to the vigil on Saturday night, especially if you usually don’t. Pay serious attention to all the Scripture readings, and think about how God is continually getting involved in the world. Think about the great “cloud of witnesses” who have gone before us, and the saints who pray for us, including your loved ones who wait for you at the heavenly reunion. Celebrate with those who are coming into the Church at the vigil.

2. Make a point to observe not only “Easter Sunday,” but Holy Thursday and Good Friday, as well. Again, especially if it’s usually only one day for you, make an effort to observe the whole of the Triduum. Go to Mass on Holy Thursday. Go to a Stations of the Cross or other liturgy on Good Friday. Take off of work if you have to (it’s a great testimony to your coworkers), and don’t use up the weekend trying to get work done — give yourself the breathing space to really think about what God has done for you in Christ.

3. Come out of Lent changed. After the Resurrection celebration (and if you’re like my family, after all the leftover ravioli are eaten), don’t just go back to the same old way everything was before Lent, as if now you can simply go back to having whatever you gave up until next year when it’s time to give up something again. Instead of going back, go forward — create some new habits, such as praying the Sign of the Cross more often as a sign to the world of your faith and devotion to Christ. Don’t give yourself permission to miss Mass so often, or if you’ve already gotten into the groove of regular Sunday Mass, give daily Mass a try, or attend Eucharistic adoration.

4. Live in gratitude. Make a conscious effort to ground your faith in what God has done in the past. Remember that gratitude for the past empowers faith in the present, and trust in God for the future. If you’re not a regular Rosary person, make a point to pray the Rosary more often, or the Divine Mercy chaplet, or at least incorporate something into your daily devotions that will remind you to count your blessings and be grateful. In fact, let your whole life be driven by gratitude. And if you don’t yet have daily devotions, make a start by doing what the early Christians did by at least praying the Our Father every day.

I wish you a blessed Paschal season!

James L. Papandrea, PhD., is the author and professor of “Church History and Historical Theology” on the YouTube channel: “The Original Church.”