Monica Dix believes that if you’re the smartest person in the room, you’re in the wrong room.

That’s why the 53-year-old artist and teacher will sometimes tack up one of her in-progress drawings where her room full of eighth-graders can see it, saying, “Okay, five things. Critique my work.”

At first, they praise her art, and tell her she’s the best artist ever.

“Then they dig in,” she said.

They always find mistakes she didn’t see, and they’re not shy about letting her know she didn’t properly measure the space between the nose and the upper lip, or that something was off about the eyes.

“It’s great for my pride,” she said.

It’s also great for her students, because it shows them not only how to look critically at the objective elements that make or break a piece of art, but it shows them what it’s like to be an artist. Sometimes you can fix a mistake, but sometimes you have to start over.

“It’s that whole ‘walk the walk.’ I let them see that,” she said.

Sometimes, a kid will point out an error she’s made, and she realizes she’s not only executed something wrong, she’s been teaching it wrong. It’s like when one person raises his hand and asks a question, and it turns out there are ten people who also had that question, but were too self-conscious to ask.

“It helps everybody,” she said.

Looking at modern art

Dix has been teaching art to teenagers at Naples Classical Academy, a charter school in Naples, Florida, since 2021. In many ways, it’s an extraordinary school, where kids leave their cell phones behind and nobody aspires to be a TikTok star. The classical curriculum, provided by Hillsdale College, tends to attract families with a certain mindset, she said.

But in other ways, they bring the same attitudes and assumptions to her class that many Americans bring to art in general. Part of the curriculum includes modern art, and every year when she introduces abstract expressionism, someone will say, “I could do that!” or “A kindergartener could do that!”

She responds, “Then why didn’t they?” She asks her students to learn what was going on in the artist’s life and what was going on in the world. They study art on the same timeline as they study history, so they begin to make connections and understand why some artists chose to break with tradition, and why we still remember their work today.

“I come at it from a historical standpoint, from a cultural history standpoint. (These things are) worth looking at,” she said.

She also gets her students to do more than just look. If they have time, she invites them to re-create art that baffles them — for instance, the intricate, dynamic layers of drips and splashes in a Jackson Pollock action painting.

It’s harder than it looks. Her students are allowed to say whether they like or dislike a piece of art, but first they should know what they’re talking about.

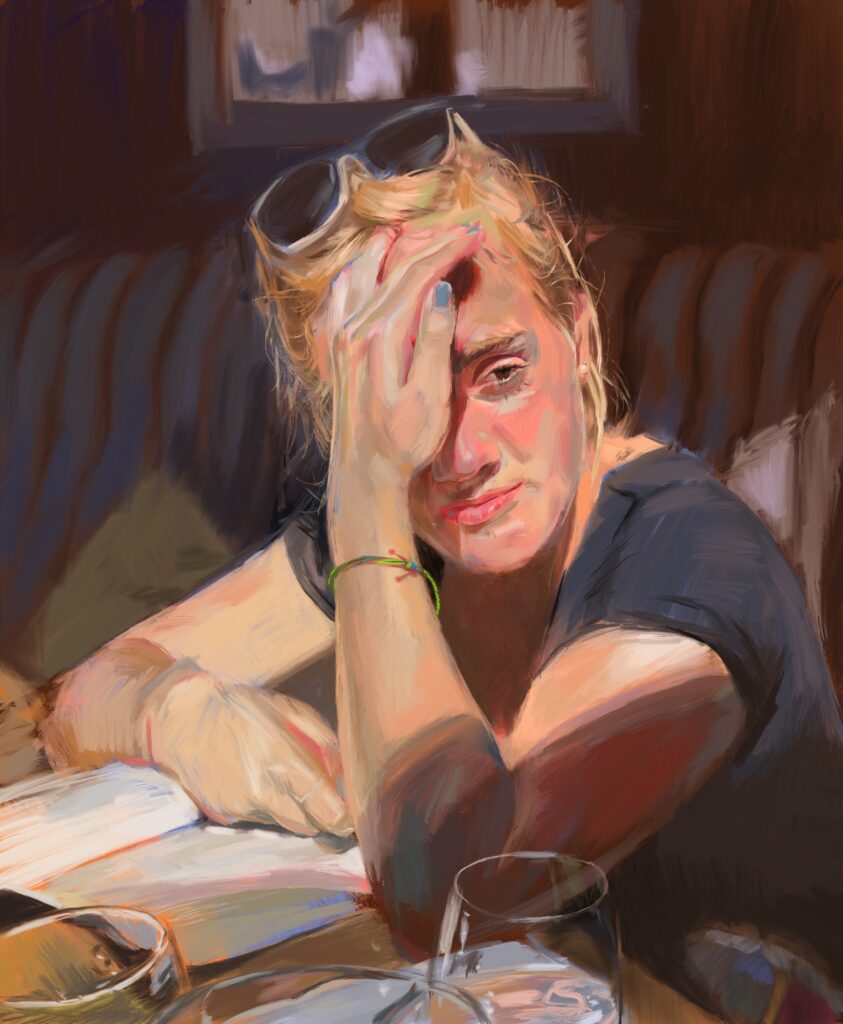

Dix makes herself walk the walk, too. When her youngest child was born in 2014, she challenged herself to draw a portrait every day for one hundred days, and painfully but vastly improved her skill. This was before teaching was even on her radar, but she was glad she had done it, because when she took a look at the curriculum, she saw she’d have to teach portraiture.

“Good thing I started on that! I taught it to myself; now I teach it to my students,” she said.

A preference for figurative art

At the end of eighth grade, she has her students reflect on how their attitudes toward art have changed — what they believed coming in, and what they believe now.

Her own training was mostly classical, and she leans toward representational and figurative art. Most of her students eventually land there, too; but it’s important for them to find their own way. She presents the facts to them and gets them in the habit of finding evidence for their assertions. At the end of the year, they often say they’re glad they understand more of the cultural and historical context for the art they used to dismiss out of hand.

“But they still prefer looking at a beautiful still life,” she said. “No one says, ‘I want to spend all day putting paint on a canvas and scraping it off.’ They get bored with it.”

There is no secret message in the curriculum to guide them toward a particular theory of art, she said.

“We just show them beautiful art, and that’s enough. We don’t have to tell them what to think.”

Most of her eighth graders are enthralled with realism, because it’s hard to do and beautiful to see; and so they spend at least a quarter of the year on observational drawing.

“My hope is, when they’re faced with a decision about what to put on a blank wall in their first apartment, they have some kind of sense of, ‘I know what to do. I know what art is,'” she said.

The entire curriculum is designed to show over and over again what the purpose of art is, as a human activity, and what it means to make it, to look at it, to live with it. It’s countercultural to insist on the importance of something without any utilitarian value; and it’s a hard sell to persuade her students that art isn’t some rarified luxury for rich people, and not off-limits to the working class.

A glut of images

Part of the problem is the glut of images we’re all exposed to every day. She tells her students that the impressionist master Monet would get up in the morning, see the paintings in his house, look outside, and begin to paint. By the end of the day, he had seen maybe a dozen images.

“The rest of us, even non-artists — how many images have you seen? Probably thousands. We’re inundated. It numbs us,” she said.

It sounds odd for an artist to beg people not to look at so many things, but that’s what she does. “Be contemplative and selective about what you look at. It’s the ultimate mortification: “Continence of the gaze,” she said.

It’s an impulse that hasn’t disappeared entirely from modern society.

“We still send people to art school when we could send them to Target,” she said.

Learning to make art ourselves — or even to bake bread or make crafts — is a way of rediscovering our own humanity.

“In slowing it down, being more aware of the human activity in making art and in receiving art, the dignity of the person comes through,” she said.

She even feels the same way about cooking.

“All people should work in a restaurant, or never go out to eat,” she said. “If you’re going to be a good diner, you should be on the other side, and understand what you’re really asking.”

Doing the prep work, cooking, cleaning up afterward is dignified work, and maybe harder and more meaningful than it looks.

Most of her students aren’t Catholic, and she’s not there to proselytize, but she believes she’s expressing her faith when she teaches this deliberate, intentional approach to art.

“I see it as ‘do unto others,'” she said. “It’s not exclusively Catholic, but it’s a good way for me to express my beliefs in a way that’s walking the walk.”

The one message she tries hard to make sure all her students hear: “Do it yourself, and pay attention.”