This is the fourth in a series looking at the Church’s 12 most recent popes and the marks they’ve made on the Church. The series appeared each month throughout 2018.

“Are there are any Catholics here?” Given the setting — the Vatican’s apostolic palace — the question was more than slightly gauche. It was spoken by Woodrow Wilson near the end of the first-ever meeting between a U.S. president and a pope — in this case, Benedict XV. Their encounter on Jan. 4, 1919, occurred as Wilson was on his way to Versailles, France, for the ill-fated peace conference after World War I.

At the end of the audience, Pope Benedict said he would give his blessing. Wilson, a Presbyterian who was none too fond of the Catholic Church, looked uncertain. The pope assured him the blessing would be for non-Catholics as well as Catholics. The president then turned to his entourage and told the Catholics to step forward and get blessed. As he surely knew, that included his faithful personal secretary, the Irish-American Joseph Tumulty.

As promised, Benedict blessed the group. The Catholics knelt. Wilson remained standing, head bowed.

What had these two very dissimilar men, Woodrow Wilson and Benedict XV, talked about before the blessing? Obviously, peace. Each had authored peace proposals. Benedict’s were dismissed by the victorious allies, who considered it too accommodating to Germany. Wilson intended to press his 14-point plan at Versailles. But as things turned out, it was set aside by the others in favor of a punitive settlement that embittered the Germans and set the stage for a still deadlier war just two decades later.

Fairly or not, historians assign much of the blame for the fiasco at Versailles to Wilson’s high-minded bungling. As for Pope Benedict, he badly had wanted to be represented there, but the anti-clerical French and Italian governments were having none of that. For the Church, it may have been a blessing in disguise. At least no one could blame the pope for the disastrous peace-that-was-no-peace.

Path of diplomacy

Benedict XV often is said to be an unknown pope. He deserves better. Heading the Church at a critical moment in world history, he responded to the monumental human suffering of the so-called war to end all wars with notable intelligence and compassion, while his diplomacy, though not successful, marked the Holy See’s re-entry into serious world affairs after a century of being excluded.

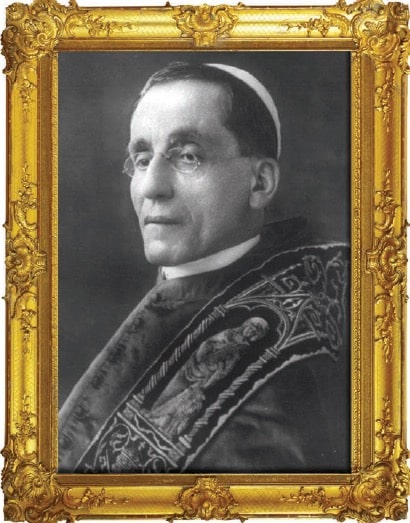

| Benedict XV at a glance |

|---|

|

Born Giacomo Giambattista della Chiesa on Nov. 21, 1854 Ordained a priest in 1878, a bishop in 1907 and made a cardinal in 1914 Pope from Sept. 3, 1914-Jan. 22, 1922 Promulgated the first Code of Canon Law in 1917 Intensified the Vatican’s diplomatic and humanitarian efforts in response to World War I. |

Giacomo della Chiesa was born in Pegli, Italy, on Nov. 21, 1854, to a noble but far from wealthy family. His birth was premature, and the child grew up diminutive in stature and frequently in poor health. His father, a lawyer, wanted his son to follow him in the legal profession, so he obediently studied law at the University of Genoa, earning a doctorate in civil law in 1875. But then the young man’s preferences prevailed, and he entered the seminary, studying in Rome and receiving doctorates in theology and canon law.

Ordained a priest in 1878, he trained for the papal diplomatic corps at the “Accademia” — the Academy of Noble Ecclesiastics, where future Vatican diplomats studied. There he attracted the attention of Archbishop Mariano Rampolla, who chose the young man as his secretary upon becoming papal nuncio in Spain.

In 1887, Rampolla was named cardinal and secretary of state, and della Chiesa returned with him to Rome, eventually becoming undersecretary. He continued in that position under Pope St. Pius X and Rampolla’s successor, Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, until 1907, when the pope named him archbishop of Bologna, Italy — a promotion dictated at least in part by the desire to get him out of Rome. Although Bologna traditionally was headed by a cardinal, internal Vatican politics delayed his elevation to that rank until 1914.

Pius X died just three months later, on Aug. 20. As often happens in papal elections, the cardinals in the conclave that followed wanted a change, and, with war underway, turned to Cardinal della Chiesa, a seasoned diplomat known to have been at odds with the policies of the previous pontificate.

Canon law, missions, war

Although World War I and its immediate aftermath dominated the pontificate of Benedict XV, he found time to tend to other issues. Generally speaking, he continued the anti-modernist line of his predecessor, but with notably less rigor. (One of his discoveries after becoming pope was that the anti-modernist crusaders had kept a file even on him.) He promulgated the first Code of Canon Law, the preparation of which had been launched by Pius X. He took steps to improve church-state relations in France and Italy.

And on Nov. 30, 1919, he published an encyclical, Maximum Illud, setting out a far-sighted policy on missionary work. While commending foreign missionaries for their zeal, the pope reminded those responsible for missions of the importance of forming native clergy.

“Wherever, therefore, there exists an indigenous clergy, adequate in numbers and in training … there the missionary’s work must be considered brought to a happy close,” he wrote. The encyclical cautioned missionaries against linking their efforts to the imperial ambitions of their home countries. By these standards, the pope remarked, some accounts of missionary work made “very painful reading.”

But it was the war that mattered above all.

World War I began in 1914 amid expectations it would not last long. Religious leaders strongly supported their countries’ military adventures. Four years later, as the conflict finally drew to a close, as many as 10 million soldiers and sailors had died and many more had been wounded. Sometime after the fighting, Winston Churchill gave this account of it:

“Neither peoples nor rulers drew the line at any deed which they thought could help them to win. Germany, having let hell loose, kept well in the van of terror, but she was followed step by step by the desperate and ultimately avenging nations she had assailed. … Torture and cannibalism were the only two expedients that the civilized, scientific Christian states had been able to deny themselves: and they were of doubtful utility.”

Benedict XV opposed the war from the start. His first encyclical and others that followed called urgently for peace. In the face of criticism from all parties to the conflict, the pope refused to take sides — a policy fiercely resented by combatants who all considered themselves in the right. Instead the Holy See labored to relieve the suffering. Its efforts included creating a special office to collect information on prisoners of war and share it with their families, arranging for some 26,000 wounded and sick men to convalesce in Switzerland, spending 82 million lire — a huge sum at the time that seriously strained Vatican finances — on humanitarian relief, and lobbying the warring governments on behalf of peace.

Pope Benedict displayed notable prescience in tapping two future popes for important postwar diplomatic posts — the prefect of the Vatican Library, Archbishop Achille Ratti, as legate to Poland, and Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli of the Vatican Secretariat of State as nuncio in Munich and, shortly, in the new German republic. Archbishop Ratti was to become Pius XI, succeeding Benedict XV. Archbishop Pacelli succeeded Pius XI as Pius XII.

‘Courageous prophet’

And of course there was the pope’s peace plan. Its elements included: significant arms reduction; arbitration to settle disputes; freedom of the seas; no reparations except in special cases; restoration of the territorial integrity of Belgium and the return of other occupied territories, including German colonies; peaceful settlement of territorial conflicts; and restoration of independence to Poland, Armenia and the Balkan states.

These steps, the pope said, were needed to halt a war that by then had become “a useless massacre” and to prevent “the recurrence of such conflicts.” Some of the 14 points of Woodrow Wilson’s peace plan seemed to mirror similar thinking. But the consensus of the allies at Versailles was tragically different: a settlement providing for harsh reparations that would cripple Germany.

Addressing national leaders at the close of his peace proposals, Pope Benedict told them, “On your decisions depend the rest and joy of countless families, the life of thousands of young people, in short, the happiness of the peoples, whose well-being it is your overriding duty to procure.” The treaty that those leaders actually produced was formally repudiated by German dictator Adolf Hitler on March 16, 1935.

Among the scourges following the Great War was a worldwide influenza epidemic in which many millions died (estimates range from 20 million to as many as 100 million). Benedict XV contracted the disease and died on Jan. 22, 1922, from the pneumonia that followed.

While Benedict XV was largely forgotten for the remainder of the 20th century, in 2005, the newly elected Pope Benedict XVI singled out his namesake for praise. Explaining the choice of his regnal name at his first general audience, he said Benedict XV “was a courageous and authentic prophet of peace and strove with brave courage first of all to avert the tragedy of the war and then to limit its harmful consequences.”