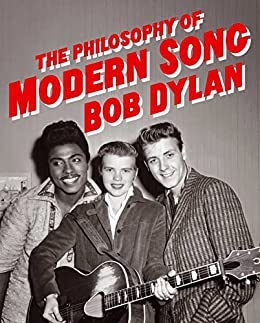

In his song, “Somedays You Write the Song,” Guy Clark wrote, “Some days you know just how it goes / Some days you have no clue / Some days you write the song / Some days the song writes you.” I thought of this lyric as I read Bob Dylan’s insightfully quirky recent book, “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” which accounts for the mystical process by which songs are made, and the mysterious effects they have on their listeners. “Being a writer is not something one chooses to do,” Dylan explains. “It’s something you just do and sometimes people stop and notice.” Often, the artist finds that she’s not in control of the muses that stir her soul to create. Thus, Dylan contends, “It’s what a song makes you feel about your life that’s important.”

A philosopher

Dylan does not attempt to explain the mystical quality of writing and performing music in some grand unified theory. He does not present us with a foundational philosophy or a set of abstract doctrines that he then applies to an analysis of the songs he discusses. The book is not a treatise about aesthetic theory, principles of harmonics or rules of melody. These do not help us “disentangle the mystery of … music,” Dylan explains. In fact, theory can get in the way of true appreciation of the song. The “more you study music, the less you understand it,” he contends. “Take two people — one studies contrapuntal music theory, the other cries when they hear a sad song. Which of the two really understands music better?”

Taking a note from Aristotle

The philosophy is there, to be sure, and at times it is profound. But Dylan is content to let the reader discern the principles from the varieties of ways he analyzes the music, whether emphasizing the lyrics, the melodies, the performance, or the personal history of the performer. Rather than to assert a unifying theory, Dylan challenges the reader to tease out a philosophy of music through his concrete discussion of individual songs. His approach is Aristotelian, taking lessons from the particularity of the songs, rather than searching for a Platonic form. “Sometimes people ask songwriters what a song means,” he complains, “not realizing if they had more words to explain it, they would’ve used them in the song.” Perhaps this is why the book has no preface or introduction. Dylan doesn’t want to explain music; he wants to talk about the songs.

Talking about the songs

It’s no surprise that he talks about them in the same eccentric (sometimes chaotic) voice characteristic of his own songwriting. To be sure, he stays focused on the music he writes about. But rather than to analyze the songs, he uses them as points of departure for his own artistic impulses. Many of the entries are actually Dylan’s prose poems inspired by the songs, rather than detached analysis of them. This is a feature, however, not a bug. Reading the book is to see how the voice of one artist inspires another. Specifically, of course, the book is about how music affects the soul of the listener. It’s about what songs do as much as what they say.

For this reason, Dylan emphasizes the necessary performance of music to appreciate the artistry of the song. The lyrics are not the song, even when they are accompanied by notes on the page. Rather, the song is in the singing. This has been a consistent element of Dylan’s own music throughout his career, as the arrangements, tempos and melodies of his songs have varied widely in live performances. Discussing the 1924 song “Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy,” Dylan explains that repeating several words three times is what makes the song effective, and why “talking is not like singing. You don’t say to someone ‘Come here, here, here,’ or ‘I’m gonna do that, that, that.’ You can sing it, though, and it makes plenty of sense.” And in his analysis of “Black Magic Woman” (1970), Dylan cautions, “it’s important to remember that these words were written for the ear and not for the eye. … An inexplicable thing happens when words are set to music. The miracle is in their union.”

St. Augustine and the heart

In this sense, “The Philosophy of Modern Song” calls to mind some of St. Augustine‘s ruminations about the powerful effects music had on his life. Reflecting on his baptism, he conveys to God how the music “flooded my ears, and your truth poured forth as a clear stream into my heart, welling up into passionate devotion; the tears flowed, and it was good for me that they did.” Not just the words, but the words conveyed by the music is what made the difference. Similarly, St. Augustine discusses the benefit of “every sweet melody to which the Psalms of David are sung.” He gently criticized Athanasius of Alexandria, who “instructed the reader of the Psalm to use so little inflection in his voice that it was closer to reading than singing.” Rather, St. Augustine was most moved by the Psalms “when they are sung by a serene voice and with the most suitable melody.”

Of course, in some sense, the distance between David’s psalms and, for example, Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart” is enormous. But the power of music to cut to the depths of the soul is constant. Whether imposing itself upon the artist or challenging the listener more deeply to examine his own life, music takes us places that we would not otherwise go. If there’s an overarching philosophy in Bob Dylan’s “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” it is that song cannot be contained by philosophy. Rather, it spills out of the bounds of theory, flooding the listener with wave after wave of emotional and spiritual power. Sometimes it carries us; other times it engulfs us. But music never leaves us dry.

Kenneth Craycraft is a columnist for Our Sunday Visitor and an associate professor of moral theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati. Follow him on Twitter @krcraycraft.