— Anonymous, Newark, New Jersey

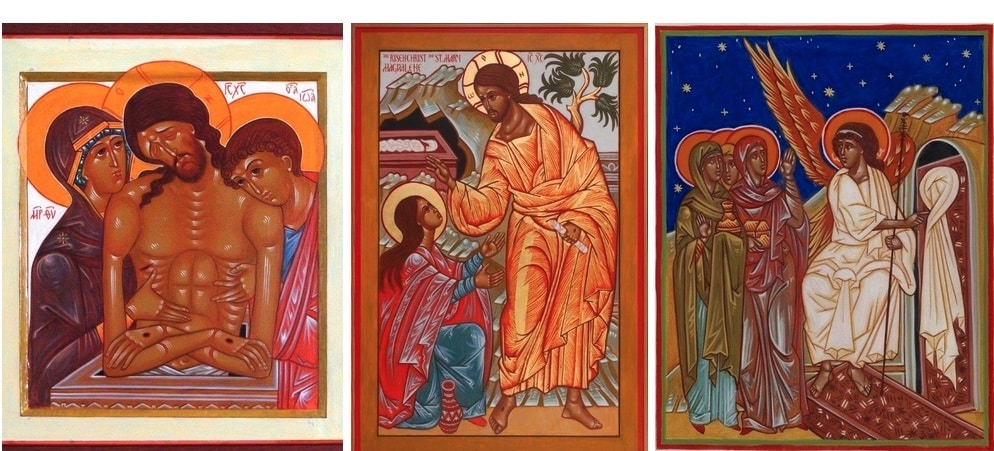

Answer: There is no rule against Roman Catholics keeping or honoring the presence of icons or a norm restricting them to Eastern Christians. The use of images, including statues, has long been permitted by the Church as a salutary reminder of Our Lord and of the heroic saints who are members of our Church family and the Body of Christ.

Especially since the Incarnation of our Blessed Lord, the ancient Jewish reticence toward depicting God or the image of God in man has been set aside. The Church also rejects iconoclasm, an ideology in the early years of the Church that sought to destroy all images and keep churches barren and empty of them.

Sources such as the decrees of Seventh Ecumenical Council at Nicaea (at which iconoclasm was condemned) and the ancient and classic work of St. John Damascene, “On Holy Images,” manifest well the ancient teaching on the goodness of icons, statues and art.

The Western Schism

Question: Centuries ago, three popes simultaneously reigned (or seemingly so). How was this resolved?

— Robert Bonsignore, Brooklyn, New York

Answer: Yes, you refer to what is often called the Western Schism, which lasted from 1378-1417. Three men all claimed to be the true pope and excommunicated one another. The incident shows the terrible political divisions among the cardinals of the Church at times. As such, it did not involve major theological differences. It took the four-year Council of Constance (1414-18) to finally resolve the matter.

Strangely the schism was set into motion by a good development: the return of the papacy to Rome under Gregory XI on Jan. 17, 1377. This ended the Avignon Papacy (1309-77), in which popes, wearied of violent political conditions in Rome and other mostly political reasons, chose to live in Avignon, France. It was a rather luxurious town in Southern France, and the Avignon Papacy developed a reputation for distance, excessive French influence and corruption that divided major parts of Western Christendom. Thanks, in part, to the influence of St. Catherine of Siena, Pope Gregory XI finally returned to Rome in 1377. After Pope Gregory XI died in 1378, the cardinals elected Urban VI, who had a reputation as a capable administrator. But he was prone to violent temper and was a poor diplomat, and many cardinals regretted their decision. A large number of them left Rome for Anagni, where, even though Urban was still pope, they elected a rival pope, Clement VII, and reestablished a papal court in Avignon. Different countries in Europe took different views as to who was the true pope, and the crisis became even worse and more complicated over the nearly 40 years of the schism.

Urban VI in Rome died in 1389, and Clement VII in Avignon died in 1394. They were replaced by their rival factions of cardinals by Boniface IX in Rome and Benedict XIII in Avignon. When Pope Boniface died in 1404, the eight cardinals of the Roman conclave offered to refrain from electing a new pope if Benedict XIII would resign. But the Avignon cardinals refused, and thus the Romans elected Pope Innocent VII. When other ecclesial and secular attempts to end the horrible divisions failed, there was a call for a council to settle the matter. Just before it convened, the council collapsed, and a group of cardinals met separately and elected yet a third pope, Alexander V.

After more intrigue and battles, a council was convened in 1414 at Constance that finally resolved the issue. It was endorsed by Pope Gregory XII, by then the Roman pope, and this ensured the legitimacy of any election. The Council of Constance, in order to proceed, secured the resignations of John XXIII and Pope Gregory XII in 1415, and it excommunicated Benedict XIII, who had refused to step down. The council elected Pope Martin V in 1417, essentially ending the schism, even if some small factions held for a brief time in Europe.

A true mess indeed, but one of the most ignoble moments in Church history was over by 1417. There are many lessons to be learned in this sad chapter, but chief among them is the danger of the Church becoming too worldly, wealthy and intertwined with secular politics.

Msgr. Charles Pope is the pastor of Holy Comforter-St. Cyprian in Washington, D.C., and writes for the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C. at blog.adw.org. Send questions to msgrpope@osv.com.