Think of it. Ever since Jesus turned over tables, called Herod a fox and pretentious religious authorities hypocrites – ever since Jesus told Pilate he really had no power over him at all — Christians often have been, as I said, unreliable citizens of the normal. Unjust laws, uncharitable customs, nonsensical hegemonic ideologies: all have been subject to the derision and sabotage of Christian believers. Or, at least, such silly wickedness should have been derided and destroyed — if Christians were being faithful, that is.

| November 6 – 32nd Sunday in Ordinary Time |

|---|

|

2 Mc 7:1-2, 9-14 |

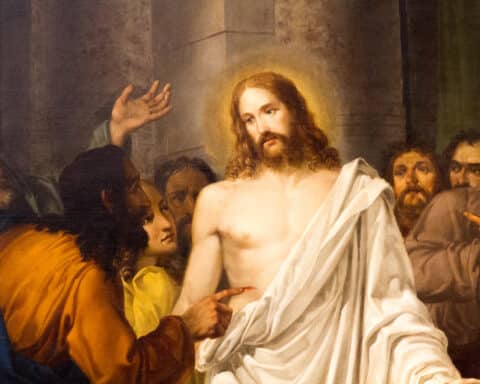

I’m reflecting here upon Jesus’ argument with Sadducees that Luke records, from which the Church takes this Sunday’s Gospel reading (Lk 20:27-38). Two facts are brought to the fore. First, the fact of the resurrection: the Sadducees, those aristocratic unbelievers in angels or an afterlife, challenge Jesus to explain what they consider a contradiction arising from belief in the resurrection — Whose wife will that woman be? Now, Jesus’ answer basically is to say that resurrected life is of a different kind than earthly life and that making such comparisons and asking such questions is little more than nonsense. Of course, saying this, Jesus doesn’t win the argument; he just silences them. This is indeed only right, for winning arguments about belief in the resurrection, at the end of the day, doesn’t matter; and that’s because Jesus will in fact rise from the dead and bid his disciples to believe in it, which is something more profound than winning silly arguments.

And this fits with the second fact brought to the fore in this passage from Luke. Christians are called to believe in the Resurrection and to have faith in the Risen Christ. But, just like Jesus, we hold that belief sometimes surrounded by scorn. The Sadducees were comfortable materialists. They had no need or inclination to hope for anything better. Their wealth blinded them to the eternal. The comfortable sophisticates in the Aeropaus laughed at Paul.

The middle-class atheists of our own age just can’t see beyond the simple façade of the material. And thus, the ethics of materialists and the ethics of resurrectionists differ: the former embraces the violence of scarcity while the latter (that is, Christians) embrace the charity of eternity. That’s why Christians, for instance, feel the need to make friends with the poor while others just want to do away with poverty altogether; and there is a quite sinister difference between these two ways of thinking. And this, of course, is but one example of the fight between Christians and the world. My point is simply that just as Jesus was talking on a completely different level the Sadducees couldn’t fathom (hence, their silence), so too do Christians inhabit a very different world — a world viewed as utterly different because of the difference heaven makes.

Which, as I suggested at the start, should make us rebels, not entirely reliable citizens of the normal. From Jesus to Paul to the martyrs to Martin Luther King, Jr. to you and me: that’s what we’re called to be — radical believers in the resurrection of Christ, more trustworthy for heaven than here.

Father Joshua J. Whitfield is pastor of St. Rita Catholic Community in Dallas and author of “The Crisis of Bad Preaching” (Ave Maria Press, $17.95) and other books.