Most Catholic Christians go through life seeking the one who is hidden from us. We are like someone entering a dark room and fumbling for the light switch. We want and need the light, just like we want and we need God. Jesus and his Church provides us with ways to find that Light. Among the most prominent are the sacraments — seven visible signs, sources of grace, given to us by the one we cannot see. They are part of a Catholic’s life from birth to death.

“Sacraments,” according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “are efficacious signs of grace instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Catholic Church by which divine grace is dispensed to us” (No. 1131) Efficacious meaning, effective, prevalent, believable. Another definition, often heard in an RCIA (OCIA) session: “a visible sign of an invisible grace.” An example is when we see two family members exchange a hug, we can see the embrace and know that love is present but we can’t see it. The hug is the visible sign and the love is the invisible yet believable result.

These are the sacraments given to the Catholic Church by Jesus: baptism, confirmation, the Eucharist, penance, anointing of the sick, holy orders and matrimony. Evolving over the centuries, seven was not always the number of sacraments; at different times, there were as few as two and as many as 30. There were periods when rituals concerning the feet washing ceremony, candles, holy water, sign of the cross and others that had sacraments linked to them. At the 16th-century Council of Trent, the bishops affirmed the seven sacraments we have today and made them an article of faith: “If anyone says that the sacraments of the New Law were not instituted by Jesus Christ, Our Lord, or that these are more or less than seven, namely, baptism, confirmation, Eucharist, penance, extreme unction, order and matrimony or that anyone of these seven is not truly and strictly speaking a sacrament-let him be anathema” (Canon 1, Session VII). Clearly, we believe that the sacraments have their origin in Jesus, and that he proclaims them through the Church. Three of these sacraments are never repeated: baptism, confirmation and holy orders; they impart an indelible seal on the soul of the recipient.

Non-Catholics often ask, “Where are the sacraments named in the Bible?” Their thinking is that the Ten Commandments are clearly listed, as are the beatitudes, but where is a list of sacraments? There is no such list, but the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church are clearly established in sacred Scriptures.

Sacrament of Baptism

Preaching by the apostles was not limited to the synagogue. Lydia, a dealer in purple cloth, heard Paul speak along a river bank (cf. Acts 16:13-15). The Philippi jailer was converted in a jail (cf. Acts 16:25-34). Cornelius, the Roman centurion, listened to Peter in the centurion’s home (cf. Acts 10:44-49). Deacon Phillip explained the sacred Scriptures to the Ethiopian eunuch along the road between Gaza and Jerusalem (cf. Acts 8:26-40). According to the Scriptures, these individuals, and in most cases all their families including children, were baptized during the referenced encounters. The same Scriptures describe the Holy Spirit as being present at each of these baptisms, all of which can be traced to the example of Jesus’ baptism (cf. Mt 3:3-17). His baptism by John the Baptist foreshadows every other baptism and established baptism as a sacrament.

John the Baptist prophesied the need to repent and be baptized because the Messiah was coming. His baptism forgave sins, a baptism of repentance; it did not confer grace but prepared people for the one they had long been waiting for. John told all who would listen that he baptized with water while Jesus would baptize with the Holy Spirit. In Matthew (3:15-16), Jesus approached John for baptism. Our Divine Savior had no need of baptism, but he associated himself with sinners in this manner because it was God’s plan for him and for the salvation of mankind. So, on a river bank, in the presence of the Father and the Holy Spirit, Jesus was baptized. Through that action, Jesus sanctified and instituted the Sacrament of Baptism. He later defined the need for baptism to Nicodemus: “Amen, Amen, I say to you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit” (Jn 3:5). Baptism opens the door to all the other sacraments and, along with Confirmation and Eucharist, is among the Sacraments of Initiation.

Sacrament of Confirmation

The Acts of the Apostles details that Jesus, through the apostles, established confirmation as a sacrament. After receiving the gift of the Spirit at Pentecost, the apostles went down to Samaria to preach to those who had chosen to follow Our Lord Jesus. Peter and John arrived and “prayed for them, that they might receive the holy Spirit, for it had not yet fallen upon any of them. … Then they laid hands on them and they received the holy Spirit” (Acts 8:14-17). We read in Acts (19:1-7) about Paul laying hands on people in Ephesus who had been baptized with the baptism of John. Learning that they knew nothing of the Holy Spirit, he baptized them in the name of Jesus and then instilled them with the Holy Spirit: “And when Paul laid [his] hands on them, the holy Spirit came upon them, and they spoke in tongues and prophesied.”

When the Holy Spirit descended on those gathered in the Upper Room at Pentecost (cf. Acts 2), the apostles, who had been hesitant, fearful, even cowardly, suddenly became undaunted witnesses to Jesus. Such is the case during every Sacrament of Confirmation; the one receiving the Holy Spirit, receiving the laying on of hands and the holy oil, are bestowed with the same courage given the apostles — that is, those confirmed become soldiers of Christ and are meant to share their good news.

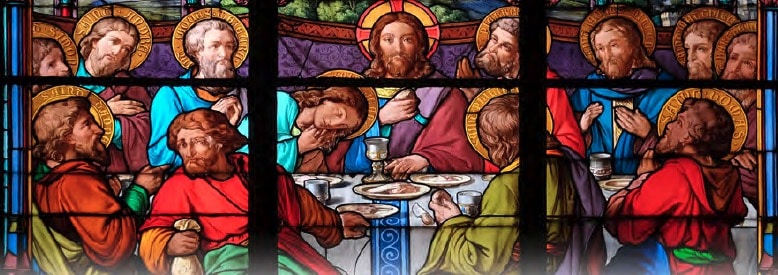

Sacrament of the Eucharist

St. Justin Martyr (100-165) provides an example of how the Eucharist was received by those newly baptized in the second century: “After we have washed someone who has been convinced and has accepted our teaching, we bring him to the place where those who are called ‘brethren’ are assembled, [probably someone’s home].” They all prayed together, and the president of the brethren received the bread and the wine. “Taking them, he gives praise and glory to the Father of the universe, through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and he offers thanks at a considerable length that we have been counted worthy to receive these things from his hands. … And when the president has given thanks, and all the people have expressed their assent, those who we call deacons distribute to each of those present a portion of the bread and wine mixed with water, over which the thanksgiving was pronounced” (First Apology, No. 65). Once churches were built, and assuming the bishop was available, those baptized would be brought inside the Church, receive the laying on of hands, anointed and then participated in the Liturgy of the Eucharist. A newly baptized infant was given a few drops of the precious blood.

Sacrament of Marriage

The purpose of marriage is the procreation of children and bringing them up in the Church as well as the husband and wife mutually helping each other attain eternal life — heaven. God is at the center of every marriage, and his relationship with man and woman is identified in the scriptures, found first in Genesis: “The Lord God said: It is not good for man to be alone” (2:18). Then Scripture tells us, from man’s rib he created woman (cf. 2:22). Here in the garden of Eden, God proclaimed and blessed the marriage of Adam and Eve, the first marriage. “That is why a man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, and the two of them become one body” (2:24).

The first miracle performed by Jesus took place at a wedding, the Wedding at Cana (cf. Jn 2:1-11). That marriage was blessed and graced by the presence of Our Lord. In the same manner, Jesus, through the priest, is present at every wedding. His being at Cana was not by chance; his presence, the miracle he performed, signals the act of marriage as being unique in the eyes and hands of God. It is a sacrament.

As stated by the Council of Trent: “If anyone says that Matrimony is not truly and properly one of the seven sacraments of the New Law, instituted by Christ our Lord, but was invented by men in the Church and does not confer grace, let him be anathema” (Canon 1, Session 24).

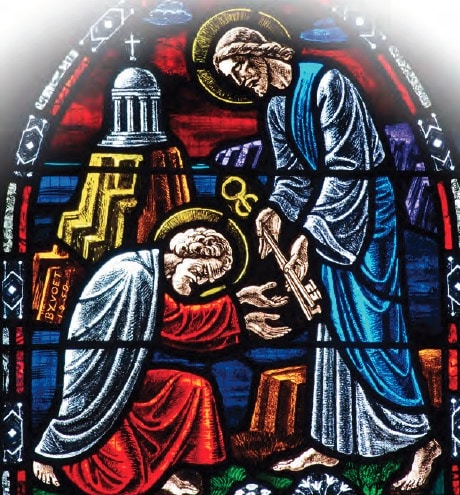

Sacrament of Holy Orders

One of the first scriptural references to ordinations is found in Acts (6:1-7). The apostles said they were in need of others to distribute alms: “Brothers, select from among you seven reputable men, filled with the Spirit and wisdom, whom we shall appoint to this task.” These were the first deacons in the Church. They were presented to the apostles “who prayed and laid hands on them.”

The Council of Trent said: “Whereas, by the testimony of Scripture, by Apostolic tradition and the unanimous consent of the Fathers, it is clear that grace is conferred by sacred ordination, which is performed by words and outward signs, no one ought to doubt that Order is truly and really one of the seven sacraments of the holy Church” (Session 23, Chapter III).

Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick

In the Gospel according to Mark, Jesus sent the apostles out with “authority over unclean spirits. … They drove out many demons, and they anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them” (6:7, 13). Here then is an indication that holy oil in the hands of the apostles had special qualities that, if not to cure, are to provide encouragement to the sick. This sacrament is today administered by our priests.

That the anointing of the sick is a sacrament is clear in the book of James: “Is anyone among you suffering? He should pray. Is anyone in good spirits? He should sing praise. Is anyone among you sick? He should summon the presbyters of the church, and they should pray over him and anoint [him] with oil in the name of the Lord, and the prayer of faith will save the sick person, and the Lord will raise him up. If he has committed any sins, he will be forgiven” (Jas 5:13-15). The bishops at the Council of Trent concluded that extreme unction “was instituted by Christ our Lord as truly and properly a sacrament of the new law, insinuated indeed in Mark, but recommended and promulgated to the faithful by James the Apostle” (Session 14, Second Decree, Chapter I).

Sacrament of Confession

Are there any more precious or desired words than those of absolution given by the priest in the confessional? As the representative of Jesus, the priest says, “I absolve you of your sins.” There is no sin the Church cannot forgive, and forgiveness awaits us in the Sacrament of Confession. Here again the effectiveness of the sacrament depends on the disposition of the person receiving it.

As is the case with the other sacraments, when we go to confession, we experience a personal encounter with Christ. An example of such an encounter and belief in the power of Christ is found when Jesus healed the woman who was hemorrhaging for 12 years, “[She] came up behind him and touched the tassel on his cloak. She said to herself, ‘If only I can touch his cloak, I shall be cured.’ Jesus turned around and saw her, and said, ‘Courage daughter! Your faith has saved you.’ And from that hour the woman was cured” (Mt 9:20-21). She had the right intention, sought out his presence and was healed.

D. D. Emmons writes from Pennsylvania.

| Baptism and confession in the early Church |

|---|

|

Some at the time argued that there was no forgiveness after baptism; another belief was that you could be forgiven but only once. Hermas, a second-century author, wrote: “‘I have heard sir … that there is no other penance except that which took place when we went down into the water and obtained remission of our former sins.’ He said to me, ‘You have heard rightly … one who has received remission of sins ought never to sin again but live in purity. … But I say to you … after this great and holy calling, if a man be tempted by the devil and sin, he has one repentance. But if he sin and repent repeatedly — repentance is of little value to such a man, and with difficulty will he live'” (“The Shepherd,” A.D. 140-155). |

The first Christians believed that once baptized, a person would never again sin, and thus there was little focus on confession or on reconciliation. Those individuals, until at least the fourth century, risked their lives to become Christians, to be baptized. If found out, they could be persecuted, if not killed.

The first Christians believed that once baptized, a person would never again sin, and thus there was little focus on confession or on reconciliation. Those individuals, until at least the fourth century, risked their lives to become Christians, to be baptized. If found out, they could be persecuted, if not killed.