Appropriately for an eminent lawyer, the turning point of St. Thomas More’s life came during a trial. But unlike other trials in which he’d been involved, this time he was the one on trial — accused of the heinous crime of treason to the king he had faithfully served.

To More, the issue at stake was something far greater than his life. If he saved himself by doing as Henry VIII wished, he would be party to a schism that threatened — and nearly accomplished — the destruction of English Catholicism by separating it from the pope. That was something this loyal servant of the king would not do, even if refusing meant his death.

“No more might this realm of England refuse obedience to the See of Rome,” he patiently told his judges, “than might a child refuse obedience to his own natural father.” To no one’s surprise, least of all his own, they found him guilty.

Thomas More’s trial was his finest hour. But he had in effect begun preparing for it years earlier.

Early years

Born in London on Feb. 7, 1478, the second of six children of well-to-do parents, he served as a page in the household of the archbishop of Canterbury and attended Oxford University. After taking up the study of law, he lived near a Carthusian monastery, frequently worshipped with the monks, thought seriously of becoming one himself, and began wearing a hairshirt, a practice he would continue for the rest of his life.

In 1502, More began to practice law. The following year, he was elected to parliament. Marrying in 1505, he and his wife had four children before her death in 1511. Seeking a mother for his young children, he quickly married a widow. Although he and his new wife had no children, he welcomed the daughter of her first marriage and later became guardian of two young girls.

Read more from the Turning Point series here.

In addition to his successful career in law and public service, More was part of an international group of Catholic humanists that included the eminent Erasmus of Rotterdam. Erasmus is generally considered to be the first to call More “a man for all seasons” — a description that became the title of Robert Bolt’s very successful 1960 play about More and the film based on it.

‘Utopia’

Eagerly cultivating the new learning of the early Renaissance, humanists like More also advocated reforms in the Catholic Church. Both interests — humanism and reform — are reflected in his writing, and nowhere more than in his book “Utopia,” a work that is still read and enjoyed today.

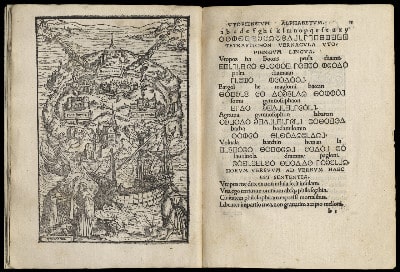

Published in 1516, “Utopia” (the name is Greek for “no place”) is a subtly ironic work describing an imaginary land whose beliefs and practices stand in implied contrast with the failings of European society as it was in the 16th century. The book was written in Latin, the international language of that day. At the same time, its fictional framework — in an age when, as one translator remarks, “rash expressions of opinion were apt to land one in the Tower” — made it possible for the author to air views that might otherwise have caused him trouble.

In light of later events nonetheless, the closing words of a Utopian prayer as More gives it seem almost to anticipate what lay ahead:

“Grant me an easy death, when Thou takest me to Thyself. I do not presume to suggest

whether it should be late or soon. But if it is Thy will, I would much rather come to Thee by a most painful death, than be kept too long away from Thee by the most pleasant of earthly lives.”

Trouble brewing

Knighted in 1521, More pursued a career that included important diplomatic missions and serving as an advisor to King Henry VIII. In 1529, he succeeded Cardinal Thomas Wolsey as Lord Chancellor, the second highest office in the kingdom after the monarchy itself.

These were the early years of the Protestant Reformation, and King Henry was its staunch opponent. More moved vigorously to suppress Protestantism in England, and several Protestants were executed. Centuries later, Pope St. John Paul II remarked that in this matter, More “reflected the limits of the culture of his time” — a time when Catholics and Protestants found it natural to persecute one another.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing in another quarter. Increasingly frustrated at the failure of his wife, Catherine of Aragon, to bear a son to succeed him, and infatuated with a young woman named Anne Boleyn, Henry set Catherine aside and sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. Seeing that all this would end badly, More resigned his office in May of 1532.

“Moderation, virtue and goodwill, honesty, learning, and genius were all unavailing against the dark side of history,” a historian comments.

‘A greater benefit’

More had hoped for a quiet life, but that was not to be. After a long delay, Pope Clement VII finally said no to the annulment, and Henry went on a rampage. Having forced Parliament to declare him supreme head of the Church in England, he now obtained an enactment requiring the taking of an oath affirming his supremacy and set about executing dissenters.

Except for Bishop John Fisher of Rochester, the English bishops accepted Henry’s new ecclesiology. More kept his silence, but he did not take the oath. Knowing that the silence of so eminent and respected a man was itself an unspoken criticism of his policy, Henry ordered him arrested. On April 17, 1534, More joined Bishop Fisher in the dreaded Tower of London.

There he stayed for nearly 15 months, writing, praying and rejecting repeated attempts — by his family and emissaries of the king — to get him to change his mind. Bishop Fisher, whom Pope Clement had by now named a cardinal, was executed on June 22, 1535. On July 1, More was taken from the Tower to Westminster and tried on charges of promoting sedition and insulting King Henry. At this turning point, he might still have saved himself by taking the oath. Instead, he finally spoke his mind:

“This indictment is based upon an act of parliament directly repugnant to the laws of God and his holy Church whose supreme government in whole or part no temporal ruler may presume to take upon himself. That right belongs to the See of Rome — a spiritual preeminence conferred by our Savior himself and belonging by right only to St. Peter and his successors. This realm, being only one member and small part of the Church, may not make a particular law contrary to the general law of Christ’s universal Catholic Church. …

“Necessity alone obliges me to say so much in declaring my conscience. But it is not so much on account of the supremacy question that you seek my blood as because I would not agree to the king’s marriage.”

More was sentenced to be hung, disemboweled while living and beheaded. The king “graciously” commuted this to beheading. The execution took place on July 6. More told the executioner, “You will give me this day a greater benefit than any mortal man could give me.”

Henry VIII eventually took six women as wives. Two he executed and four he divorced. Hilaire Belloc gives this picture of the king in his latter years: “He had become so huge, unwieldy and corrupt in person that he could hardly move. … He would express, in the orders he gave, a sort of hellish savagery and greed of suffering and gloat over the agonies of his victims.”

Of Thomas More, Belloc writes that while everything else failed him in the end, “his glorious resolution stood — and that is the kernel of the affair. He had what is called ‘Heroic Faith.'”

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.