This is the third in a series that will look at the Church’s 12 most recent popes and the marks they’ve made on the Church. The series will run in the first issue of each month throughout 2018.

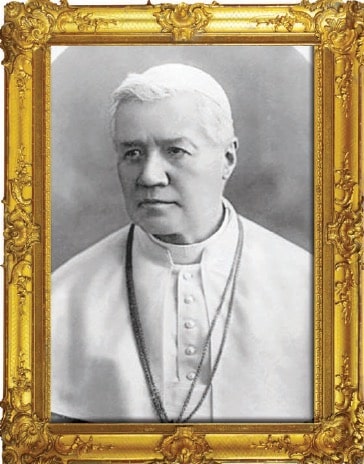

Coming to the throne of Peter in the opening years of what arguably would be the most tumultuous century in history, Pope St. Pius X chose as his motto these soaring words from the epistle to the Ephesians: Instaurare omnia in Christo (“To restore all things in Christ”; Eph 1:10). Even so, Pius X is probably best remembered not so much for restoring as for resisting.

He was a pastor at heart who, even as pope, taught a weekly catechism class in the shadow of the apostolic palace. But this was a pastor with a backbone of steel, visible in his defiance of hostile secularism wielded as a weapon against the Church by the anticlerical government of France, as well as in his determined effort to stamp out an emergent heresy that he called “modernism.”

His critics complain that in both cases he was too tough, too ready to fight. Yet taking an overview of the troubled course of the 20th century, these early manifestations of anticlerical secularism and the assault on orthodoxy can be seen as signs of the repeated conflicts in which successor popes would be put to the test to defend the Faith against secular rulers with an ideological hatred of the Church and would-be reformers from within seeking a break with the Tradition.

Rising to become pope

Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto was born June 2, 1835, in the village of Riese in northern Italy, the second of 10 children of the local postman and a seamstress. He studied at the seminary in Padua, Italy, was ordained a priest in 1858 and then spent nine years doing pastoral work.

After serving as chancellor of the Diocese of Treviso and spiritual director of its seminary, he was appointed bishop of Mantua by Pope Leo XIII in December 1884 and took steps to revitalize that moribund diocese. In June 1893, Leo named him a cardinal and appointed him patriarch of Venice. In a move reflecting tense church-state relations dating back two decades to the Italian nationalists’ seizure of the Papal States and Rome, the Italian government claimed authority to propose its candidate and for nine months blocked Cardinal Sarto from assuming the office.

After Leo XIII’s death in July 1903, his secretary of state, Cardinal Mariano Rampolla, widely was considered the likely choice to succeed him. In the conclave, however, Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary vetoed Cardinal Rampolla — the last time a Catholic monarch intervened in a papal election. Historians believe the imperial veto did not affect the outcome, but, however that may be, the voting swung to Cardinal Sarto, who was elected on Aug. 4, 1903.

A growing secularism

The problems he would face as pope had been piling up for years, with France at the head of the list. Pope Leo had pursued a policy of accommodating the anticlerical French government, and it hadn’t worked very well. Pius X and his secretary of state, Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, were determined to fight.

| Pius X at a glance |

|---|

|

Born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto in 1835 in Riese, Italy. Entered seminary in Padua, Italy, in 1850; ordained a priest in 1858 and a bishop in 1884; he was elected pope in 1903. Much of his pontificate was spent battling modernism, which he called “the synthesis of all the heresies.” Died on Aug. 20, 1914, just weeks after the start of World War I. Was beatified on June 3, 1951, by Pope Pius XII, and was canonized three years later. His feast day is Aug. 21. |

The French government already had withdrawn recognition from Catholic universities, expelled the Jesuits from France, required seminarians to serve in the military and abolished chaplaincies in hospitals and the armed forces. But when Emile Combes, a bitter ex-seminarian and prominent Freemason, became prime minister, the campaign against the Church intensified.

In 1904, the Chamber of Deputies broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See. The next year brought a new law concerning separation of church and state that ended stipends paid to priests in compensation for income lost at the time of the French Revolution and declared Church property, including churches themselves, the property of the state, with their administration in the hands of newly established lay associations.

Pope Pius responded by forbidding Catholics to cooperate in creating or operating these new bodies. When someone asked him how the archbishop of Paris could get along without house, money or church, the pope is said to have replied that when it was time to choose a new archbishop, he would name a Franciscan since a friar vowed to poverty already would be obliged by his order’s rule to live by begging.

The government now moved to force bishops and priests out of their homes and seminarians out of their seminaries. Most clergy nevertheless managed to find shelter, while contributions kept a few seminaries going.

To some extent, however, secularism — laicite the French called it — was a blessing in disguise for the Church. For the first time in French history, indeed the first time in any of Europe’s historically Catholic countries except Ireland, the government swore off involvement in choosing bishops, leaving the pope a free hand without interference from the state.

Even so, it took World War I to bring about anything resembling reconciliation between French Catholics and the anticlericals. During the war, nearly 33,000 Catholic priests served in combat as stretcher-bearers, nurses and chaplains in the field, while another 12,500 worked in military hospitals. Of this body, 4,618 priests died in battle and more than 13,000 received military decorations. Against this background, the patriotism of the French clergy could hardly be questioned.

Battling modernism

Modernism represented a very different kind of challenge. It began among a loosely linked network of scholars and intellectuals seeking to adapt Catholicism to the currents of secular thinking of the 19th and early 20th centuries in Scripture studies, history and other fields. Its two most visible figures were a French biblical scholar, Father Alfred Loisy, and an Irish-born Jesuit, Father George Tyrrell.

Writing at the time of the Second Vatican Council, Father Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, called Loisy and Tyrrell “tragic figures … who thought they could not save the Faith without throwing away the inner core along with the expendable shell. [They] show forth the mortal danger that threatened Catholicism at the first outbreak of the modern mind.”

Pius X’s response came in two parts.

On July 3, 1907, the Holy Office (predecessor of today’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith) issued a decree called Lamentabili Sane Exitu (“A Lamentable Departure Indeed”) condemning 65 propositions either taken from modernist writings, identifying conclusions to which modernism was said to lead, or expressing other unacceptable views on topics like biblical interpretation, revelation, dogma, Christology, the sacraments and the Church.

Pope Pius followed this on Sept. 7 of that same year with a long encyclical called Pascendi Dominici Gregis (“Feeding the Lord’s Flock”), tracing the philosophical and theological roots of modernism to agnosticism, the philosophy of “vital immanence” and evolutionism.

In the end, he wrote, it came down to holding that “religious sentiment” arising from the subconscious is “the germ all religion and the explanation of everything that has been or ever will be in any religion.” The source of religion, in other words, is not God’s revelation but the human need to believe.

Father Loisy refused to submit to Pascendi and was excommunicated in 1908. He died in 1940. Tyrrell, expelled by the Jesuits in 1906, was excommunicated in 1907 and died in 1909.

Three years after the encyclical, Pope Pius published an oath against modernism that priests were required to take. It remained in effect until 1967, when Blessed Pope Paul VI did away with it. More problematic were the activities of an entity called the Sodality of St. Pius V run by a Vatican official, Msgr. Umberto Benigni. This organization was a network of informers reporting on anyone suspected of modernism. Besides doing injustice to individuals, this approach did not put an end to modernism but only drove it underground, to emerge again later in the century.

Other achievements

But there was more to the pontificate of Pope Pius X than his struggles with French laicite and modernism.

Along with steps aimed at upgrading Catholic intellectual life, restoring the musical tradition of the Church and promoting catechetical instruction, he was notable for encouraging frequent, even daily, Communion and for lowering the age of first Communion to the “age of reason.” His pastoral purpose, he said, was that people should receive “strength to restrain passion, to wash away the little faults that occur daily, and to guard against more grievous sins.”

Pius X suffered a heart attack in 1913 and died of a second heart attack on Aug. 20, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I. An Anglican historian of the papacy, Dr. J.N.D. Kelly, wrote: “In many ways deeply conservative, and so regarded by contemporaries, Pius was also one of the most constructive reforming popes. A man of transparent goodness and humility as well as resolution and organizing ability, he was spoken of as a saint and credited with miracles in his lifetime.”

He was canonized by Pope Pius XII on May 29, 1954.

Russell Shaw is an OSV contributing editor.