Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez, also known as St. Oscar Romero the Martyr, is from the smallest country in Central America, El Salvador. Like Christ, Romero initially trained as a carpenter before becoming a priest. He became the archbishop of San Salvador in 1977, amid the escalating violence that would lead to the Salvadoran Civil War, and he actively spoke out against the injustices being carried out during that time. Doing so eventually led to his assassination.

Although Archbishop Romero died 45 years ago, if you venture to the beaches, hills, plains and mountains of his homeland, you will find him palpably present among his people. He continues to gaze lovingly on his flock through icons in the churches, monuments in the town squares, busts at the wayside crosses, and in the eyes of those whose spirits are lifted by his words and example.

As El Salvador rapidly grows safer and more open to tourism, there couldn’t be a better time to explore this beautiful country through the life of St. Oscar Romero. In 2015, more than 250,000 people flooded the capital for Romero’s beatification, and pilgrims have journeyed ever since to experience the landscape, culture and places that Romero called home.

The chapel where he died

For me, the most moving pilgrimage site is San Salvador’s Divine Providence Hospital. Archbishop Romero’s home in the years leading up to his death and the chapel where he was martyred are both located on the hospital’s grounds.

When my husband and I visited, the small, gated property was quiet. A few religious sisters and nurses from the hospital sat outside to have their lunch. In the chapel, a few visitors sat in the pews to pray; some prayed a decade of the Rosary during their lunch break, while others knelt for hours, praying for loved ones nearing the end of their lives in the hospital next door.

I noticed an abundance of roses growing everywhere we went. The rose is most commonly associated with the Virgin Mary, but the red rose, especially in Latin America, is also symbolic of the blood of the Christian martyrs. Pink and red roses of various shades line the four walls of the chapel — bits of beauty climbing the chain-link fencing and blooming between the barbed wires left on the wall tops from the war.

As we walked the grounds, we were met by Sister Ruby Lemus Salguero, a Missionary Carmelite of St. Teresa who lives nearby. This community of religious sisters played a significant role in caring for Romero while he was archbishop of San Salvador and now plays a crucial role in preserving his memory and relics. When Romero lived at the hospital, the sisters were his primary daily companions; when he was shot, they rushed to his side. The habit of one sister who tended to the dying martyr has become a precious relic at the shrine, as it absorbed the archbishop’s blood.

The Carmelites were not only Romero’s companions in faith and prayer, but also his friends in the final years of his life. They knew his daily habits and quirks, and during our visit, they shared many stories about Romero during his time at the hospital. These anecdotes, sometimes deeply moving and at other times charmingly funny, have been preserved and passed down orally within the convent, helping to keep the spirit of Romero present to them today.

The house where he lived

Archbishop Romero’s presence in his former home is startling. Walking through the few, small rooms, one has the sense that he just stepped out for an errand and might return at any moment with his afternoon pan dulce and coffee. His clothes hang neatly in his closet, his books stand on their shelves, his mismatched floral dishes wait by a small sink, and even his half-used tube of toothpaste (Sensodyne, if you’re curious) has been left in the bright little bathroom. You’d expect him to walk back through the door were it not for a few details freezing the rooms in time, most especially the wall calendar, dated Marzo 1980. The only note on the calendar is a small cross and the time 6:15 p.m. written in blue ink on Lunes 24, the time and day of his death.

As we stood in the quiet bedroom, Sister Ruby explained that she likes to listen to the saint’s voice. Seeing our confused faces, she pulled out her smartphone with a St. Oscar Romero sticker on the case and opened an app called “Romero Para Todos.” She began to play one of her favorite homilies from his time as archbishop. We stood next to the crucifix where Romero had spent many days and nights in contemplation and prayer, with his blood-stained chasuble hanging in the next room, while his voice echoed throughout the space.

The sisters devote themselves to the upkeep of Romero’s home and gardens, but they have preserved it as a place where a man once lived. The house does not feel like a museum of a saint, but the humble dwelling of a man who studied, slept, showered and prayed. Romero’s belongings, scattered around the house, are reminders of how contemporary his life was to ours. His shelves are filled with Parker fountain pens, his Bulova watch, mundane documents such as his passport and driver’s license, and collections of photographs he took throughout his lifetime.

For a Canadian like myself, the most charming of Romero’s belongings was a small collection of knitted winter hats for, as the sister explained, the chilly evenings. Seeing the winter hats felt familiar and homey, yet out of place in a city that averages 68 degrees Fahrenheit at night. It made me smile to think of this man, often depicted wearing a cassock and crowned with a halo, putting on his knitted blue hat to go to sleep in a chilly room. The image was simple yet powerfully human, a poignant reminder of Romero’s time on earth.

But the shrine is also home to important reminders of Romero’s continued presence as a saint. The garden walls are lined with small concrete plaques of gratitude for miracles attributed to Romero’s intercession, which the sisters have preserved. The plaques are simple, with a brief “Gratitud“ followed by a date, but they are numerous, and, Sister Ruby assured us, only a small portion of the many plaques of thanksgiving made since Romero’s death.

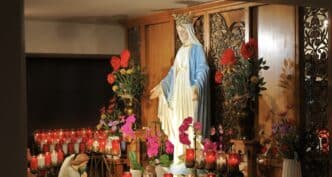

As we left, we stood in the small courtyard between a rose garden and Romero’s butter-yellow 1978 Toyota Corolla. Being surrounded by the symbols and blood-stained relics of the martyr was deeply moving, and even the roses at the foot of the Virgin Mary’s statue seemed to bow their heads as we walked the small stone path and ducked beneath the low door, just as Romero did on the evening of March 24, 1980, not knowing it would be the final time.

The crypt where he is buried

Archbishop Romero’s funeral procession was held March 30, 1980, Palm Sunday, in the historic center of San Salvador, known as El Centro. El Centro is home to the Metropolitan Cathedral of San Salvador, where Romero’s tomb is located today. The cathedral towers over Plaza Barrios, where panic reigned on the day of the funeral, when explosions and gunfire targeted the crowds of mourners. At least 31 people died after being shot or trampled in the chaos.

The crypt beneath the cathedral is where Romero is now buried. The crypt itself is rather plain and dimly lit, but it is worth the pilgrimage to kneel before his impressive bronze tomb, designed by Paolo Borghi. The sculpture depicts Romero lying in repose, yet suspended, carried by the four evangelists, whose forms serve as corner pillars to the sculpture. They carry him in a shroud, an allusion to the resurrection of the incarnate Word, who raises his saints to glory. The tomb attests to how, far from silenced by his untimely death, Romero’s words and his faithfulness to the Word remain with his flock.

The monument is filled with symbolic details. We see Romero’s mitre and crozier, symbolizing his pastoral care for the Church, and we are once again confronted with the rose. Here, the rose branch represents the special devotion Romero had to the Virgin Mary, Queen of Peace. This symbol of peace at his feet contrasts with the symbol of violence in his chest: a red jasper stone where the fatal bullet struck his heart. The four points of the cross emerge from its center. The bullet-to-cross imagery reminds us of how “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.”

A museum in his honor

The final site worth visiting is the Centro Monseñor Romero at the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA) in San Salvador. While not directly related to St. Oscar Romero, a residence on this university campus was home to six Jesuit professors and two women who were massacred by Salvadoran Army soldiers nine years after Romero’s death.

University students affiliated with the Centro Monseñor Romero provide guided tours of the site. The tour is difficult and at times graphic. We were taken through a small museum filled with blood-stained pajamas and Bibles sliced in half by machine-gun fire. Among the beautiful conacaste trees and red brick buildings of the campus, the memory of the Jesuit murders lingers in the consciousness of students and visitors alike. However, like much of El Salvador, whose soil is stained with blood, there are pockets of beauty fighting their way out of the landscape.

The courtyard where the victims were lined up and shot is now home to a small rose garden, planted in their memory. Red roses, recalling the blood of the martyrs, line the perimeter, and a small hedge of yellow roses in the center honors the two women who were killed, the wife and daughter of the gardener who planted the roses.

Adjacent to the residence, where priests still reside, is the university parish church, Jesucristo Liberador, which was built in honor of Romero. It is a highlight at the end of the tour, in part due to the artwork by Salvadoran artists Fernando Llort and Benjamin Cañas. Llort, known as the “National Artist of El Salvador,” was a close friend of Romero and is recognized for his design of the “Romero Cross.” The chapel features a triptych painted by Llort, as well as beautiful Stations of the Cross, also painted in his signature style.

On the back wall of the chapel is a contemporary depiction of the Stations of the Cross known as the “15 stations.” The 14 panels depict Christ’s passion as lived out in the sufferings of the Salvadoran people during the civil war. The 15th station is intentionally missing as a tribute to their ongoing passion.

Salvadoran sacred art frequently focuses on how Christ and Romero walked among the people, especially those typically on the outskirts of society: the poor, the suffering, the persecuted. In the UCA chapel, the processional cross is half cross and half corn. The motif of the “Christ of the Corn” is prevalent in the art of Guatemala and El Salvador, where Christ’s crucifixion is depicted as taking place in a cornfield, among people of the lowest social classes. Similarly, Romero is often depicted walking among the rural people of El Salvador, known as the campesinos, who live in impoverished areas and work laborious jobs. This is because Romero was known and loved for being a pastor who not only tended to his flock, consoled them and gave them hope, but who ultimately laid his life down for them.

The presence of Archbishop Romero is still palpable in the people and culture of this beautiful country. His warmth, generosity, humility and devotion to the faith are deeply ingrained into the consciousness of many Salvadorans, who remember St. Oscar Romero and everything he sacrificed for his country, people and God.